Forgotten may not be the best description for this man, since he has been remembered in fact earlier this year a movie ,with the title”Persona Non Grata” about him was released in the cinema. But a lot of people on the globe,including me; have never heard of this man.

I was tempted to call him the Japanese Schindler but I feel it would not do justice to him.

Although he was part of an evil regime he refused to give up on his humanity and his respect for his fellow man.

Chiune (Sempo) Sugihara, born on January 1, 1900, was the first Japanese diplomat posted to Lithuania. He was born to a middle-class family from Yaotsu, in Japan’s Gifu Prefecture on the main Japanese Island of Honshu, north of Nagoya. Sugihara is sometimes also referred to as “Chiune,” an earlier rendition of the Japanese character for “Sempo,” part of his formal name.

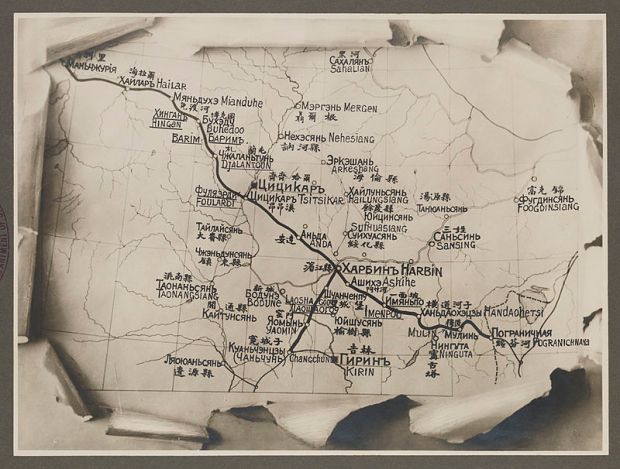

In 1912, he graduated with top honors from Furuwatari Elementary School, and entered Aichi prefectural 5th secondary school (now Zuiryo high school), a combined junior and senior high school. His father wanted him to become a physician, but Chiune deliberately failed the entrance exam by writing only his name on the exam papers. Instead, he entered Waseda University in 1918 and majored in English language. At that time, he entered Yuai Gakusha, the Christian fraternity that had been founded by Baptist pastor Harry Baxter Benninhof, to improve his English. In 1919, he passed the Foreign Ministry Scholarship exam. The Japanese Foreign Ministry recruited him and assigned him to Harbin, China, where he also studied the Russian and German languages and later became an expert on Russian affairs.

When Sugihara served in the Manchurian Foreign Office, he took part in the negotiations with the Soviet Union concerning the Northern Manchurian Railroad.

He quit his post as Deputy Foreign Minister in Manchuria in protest over Japanese mistreatment of the local Chinese. While in Harbin, he got married to Klaudia Semionovna Apollonova. They divorced in 1935, before he returned to Japan, where he married Yukiko Kikuchi, who became Yukiko Sugihara after the marriage; they had four sons (Hiroki, Chiaki, Haruki, Nobuki). Chiune Sugihara also served in the Information Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and as a translator for the Japanese legation in Helsinki, Finland.

In 1939, Sugihara became a vice-consul of the Japanese Consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania.

His duties included reporting on Soviet and German troop movements, and to find out if Germany planned an attack on the Soviets and, if so, to report the details of this attack to his superiors in Berlin and Tokyo.

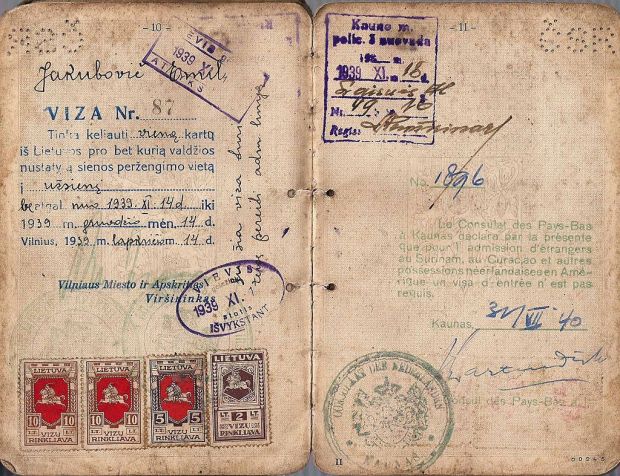

Sugihara had cooperated with Polish intelligence as part of a bigger Japanese–Polish cooperative plan.[As the Soviet Union occupied sovereign Lithuania in 1940, many Jewish refugees from Poland as well as Lithuanian Jews tried to acquire exit visas. Without the visas, it was dangerous to travel, yet it was impossible to find countries willing to issue them. Hundreds of refugees came to the Japanese consulate in Kaunas, trying to get a visa to Japan. At the time, on the brink of the war, Lithuanian Jews made up one third of Lithuania’s urban population and half of the residents of every town as well The Dutch consul Jan Zwartendijk

(Zwartendijk directed the Philips plants in Lithuania. On June 19, 1940, he was also a part-time an acting consul of the Netherlands – or, to be exact, of the Dutch government-in-exile. His superior was the Dutch ambassador to Latvia, De Decker).

had provided some of them with an official third destination to Curaçao, a Caribbean island and Dutch colony that required no entry visa, or Surinam (which was a Dutch colony).

At the time, the Japanese government required that visas be issued only to those who had gone through appropriate immigration procedures and had enough funds. Most of the refugees did not fulfill these criteria. Sugihara dutifully contacted the Japanese Foreign Ministry three times for instructions. Each time, the Ministry responded that anybody granted a visa should have a visa to a third destination to exit Japan, with no exceptions.

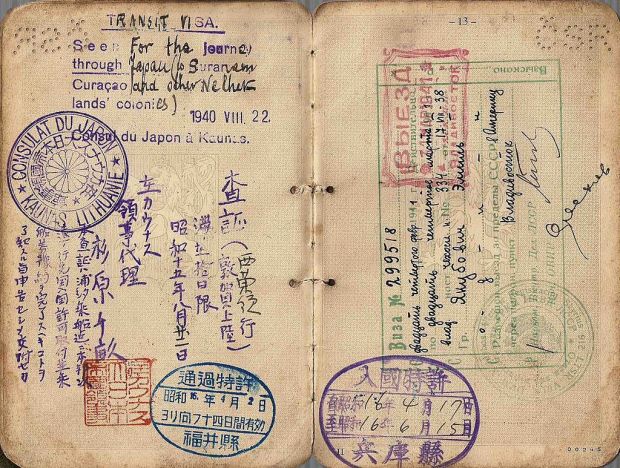

In the summer of 1940, when refugees came to him with bogus visas for Curacao and other Dutch caribbean colonies Sugihara decided to facilitate their escape from war-torn Europe. In the absence of clear instructions from Tokyo, he granted 10-day visas for transit through Japan to hundreds of refugees who held Curacao destination visas. Before closing his consulate in the fall of 1940, Sugihara even gave visas to refugees who lacked all travel papers.

Given his inferior post and the culture of the Japanese Foreign Service bureaucracy, this was an unusual act of disobedience. He spoke to Soviet officials who agreed to let the Jews travel through the country via the Trans-Siberian Railway at five times the standard ticket price.

After Sugihara had issued some 1,800 visas, he received a cable from Tokyo reminding him: “You must make sure that they [refugees] have finished their procedure for their entry visas and also they must possess the travel money or the money that they need during their stay in Japan. Otherwise, you should not give them the transit visa.”

In his response to the cable, Sugihara admitted issuing visas to people who had not completed all arrangements for destination visas. He explained the extenuating circumstances: Japan was the only transit country available for those going in the direction of the United States, and his visas were needed for departure from the Soviet Union. Sugihara suggested that travelers who arrived in the Soviet port of Vladivostok with incomplete paperwork should not be allowed to board ship for Japan. Tokyo wrote back that the Soviet Union insisted that Japan honor all visas already issued by its consulates.

Sugihara continued to hand write visas, reportedly spending 18–20 hours a day on them, producing a normal month’s worth of visas each day, until 4 September, when he had to leave his post before the consulate was closed.

By that time he had granted thousands of visas to Jews, many of whom were heads of households and thus permitted to take their families with them. According to witnesses, he was still writing visas while in transit from his hotel and after boarding the train at the Kaunas Railway Station, throwing visas into the crowd of desperate refugees out of the train’s window even as the train pulled out.

In final desperation, blank sheets of paper with only the consulate seal and his signature (that could be later written over into a visa) were hurriedly prepared and flung out from the train. As he prepared to depart, he said, “Please forgive me. I cannot write anymore. I wish you the best.” When he bowed deeply to the people before him, someone exclaimed, “Sugihara. We’ll never forget you. I’ll surely see you again!”

Sugihara himself wondered about official reaction to the thousands of visas he issued. Many years later, he recalled, “No one ever said anything about it. I remember thinking that they probably didn’t realize how many I actually issued.”

By the time Sugihara left Lithuania he had issued visas to 2,140 persons. These visas also covered some 300 others, mostly children. Not everyone who held visas was able to leave Lithuania, however, before the Soviet Union stopped granting exit visas.

The total number of Jews saved by Sugihara is in dispute, estimating about 6,000; family visas—which allowed several people to travel on one visa—were also issued, which would account for the much higher figure. The Simon Wiesenthal Center has estimated that Chiune Sugihara issued transit visas for about 6,000 Jews and that around 40,000 descendants of the Jewish refugees are alive today because of his actions. Polish intelligence produced some false visas. Sugihara’s widow and eldest son estimate that he saved 10,000 Jews from certain death, whereas Boston University professor and author, Hillel Levine, also estimates that he helped “as many as 10,000 people”, but that far fewer people ultimately survived.Indeed, some Jews who received Sugihara visas failed to leave Lithuania in time, were later captured by the Germans who invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, and perished in the Holocaust.

The Diplomatic Record Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has opened to the public two documents concerning Sugihara’s file: the first aforementioned document is a 5 February 1941 diplomatic note from Chiune Sugihara to Japan’s then Foreign Minister Yōsuke Matsuoka in which Sugihara stated he issued 1,500 out of 2,139 transit visas to Jews and Poles; however, another document from the same foreign office file “indicates an additional 3,448 visas were issued in Kaunas for a total of 5,580 visas” which were likely given to Jews desperate to flee Lithuania for safety in Japan or Japanese occupied China.

Many refugees used their visas to travel across the Soviet Union to Vladivostok and then by boat to Kobe, Japan, where there was a Jewish community. Tadeusz Romer, the Polish ambassador in Tokyo, organised help for them.

From August 1940 to November 1941, he had managed to get transit visas in Japan, asylum visas to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Burma, immigration certificates to the British Mandate of Palestine, and immigrant visas to the United States and some Latin American countries for more than two thousand Polish-Lithuanian Jewish refugees, who arrived in Kobe, Japan, and the Shanghai Ghetto, China.

The remaining number of Sugihara survivors stayed in Japan until they were deported to Japanese-held Shanghai, where there was already a large Jewish community that had existed as early as the mid-1930s. Some took the route through Korea directly to Shanghai without passing through Japan. A group of thirty people, all possessing a visa of “Jakub Goldberg”, were bounced back and forth on the open sea for several weeks before finally being allowed to pass through Tsuruga. Most of the around 20,000 Jews survived the Holocaust in the Shanghai ghetto until the Japanese surrender in 1945, three to four months following the collapse of the Third Reich itself.

Sugihara left Lithuania in early September 1940. The Japanese transferred him to Prague in Bohemia and then to Bucharest, Romania, Germany’s ally, where he remained until after the end of the war. During the victorious Soviet army’s march though the Balkans in 1944, the Soviets arrested Sugihara together with other diplomats from enemy nations. Soviet authorities held him and his family, under fairly benign conditions, for the next three years. When Sugihara returned to Japan in 1947, the Foreign Ministry retired him with a small pension as part of a large staff reduction enacted under the American occupation.

Sugihara settled in Fujisawa in Kanagawa prefecture with his wife and 3 sons. To support his family he took a series of menial jobs, at one point selling light bulbs door to door. He suffered a personal tragedy in 1947 when his youngest son, Haruki, died at the age of seven, shortly after their return to Japan.In 1949 they had one more son, Nobuki, who is the last son alive representing the Chiune Sugihara Family, residing in Belgium. He later began to work for an export company as General Manager of U.S. Military Post Exchange. Utilizing his command of the Russian language, Sugihara went on to work and live a low-key existence in the Soviet Union for sixteen years, while his family stayed in Japan.

In 1968, Jehoshua Nishri, an economic attaché to the Israeli Embassy in Tokyo and one of the Sugihara beneficiaries, finally located and contacted him. Nishri had been a Polish teen in the 1940s. The next year Sugihara visited Israel and was greeted by the Israeli government. Sugihara beneficiaries began to lobby for his inclusion in the Yad Vashem memorial.

In 1985, Chiune Sugihara was granted the honor of the Righteous Among the Nations ( by the government of Israel. Sugihara was too ill to travel to Israel, so his wife and youngest son Nobuki accepted the honor on his behalf. Sugihara and his descendants were given perpetual Israeli citizenship.

Sugihara Street in Kaunas and Vilnius, Lithuania, Sugihara Street in Tel Aviv, Israel, and the asteroid 25893 Sugihara are named after him.

The Chiune Sugihara Memorial Museum in the town of Yaotsu (his birthplace), Gifu Prefecture, in central Japan was built by the people of the town in his honor.[

Also, a corner for Sugihara Chiune is set up in the Port of Humanity Tsuruga Museum near Tsuruga Port, the place where many Jewish refugees arrived in Japan, in the city of Tsuruga, Fukui, Japan.

The Sugihara House Museum is in Kaunas, Lithuania. The Conservative synagogue Temple Emeth, in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, has built a “Sugihara Memorial Garden”and holds an Annual Sugihara Memorial Concert.

When Sugihara’s widow Yukiko traveled to Jerusalem in 1998, she was met by tearful survivors who showed her the yellowing visas that her husband had signed. A park in Jerusalem is named after him. The Japanese government honored him on the centennial of his birth in 2000.

A memorial to Sugihara was built in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo in 2002, and dedicated with consuls from Japan, Israel and Lithuania, Los Angeles city officials and Sugihara’s son, Chiaki Sugihara, in attendance. The memorial, entitled “Chiune Sugihara Memorial, Hero of the Holocaust” depicts a life-sized Sugihara seated on a bench, holding a visa in his hand and is accompanied by a quote from the Talmud: “He who saves one life, saves the entire world.”

He was posthumously awarded the Commander’s Cross with the Star of the Order of Polonia Restituta in 2007, and the Commander’s Cross Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland by the President of Poland in 1996Also, in 1993, he was awarded the Life Saving Cross of Lithuania.

He was posthumously awarded the Sakura Award by the Japanese Canadian Cultural Center (JCCC) in Toronto in November 2014.

A truly great hero who proved that in order to save lives you sometimes just have to do what needs to be done without thinking of yourself.

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

Reblogged this on History of Sorts.

LikeLike