The Axis powers and mainly Germany, Italy and Japan were not the only occupying forces during WWII. The allies also occupied some nations.

After the defiant battles that the Icelandic football team fought at the 21st century battlefield of the EURO 2016 Championships I decided to have a look at this country’s history during WWII.

Iceland didn’t want any part of the Second World War. It was all tiny and defenseless and alone out there in the north Atlantic. Most of the hundred thousand people on the island were peaceful farming and fishing families. They had no army; only a few dozen hastily-trained police officers.

For the most part, the Icelandic arsenal was limited to a few pistols and rifles and a couple of antique cannons. But that was the point: ever since the end of the First World War, when they had been granted their autonomy under Danish rule, Iceland had been an officially neutral country. They weren’t going to be doing any invading — and no one was supposed to invade them.

The invasion of Iceland, code named Operation Fork, was a British military operation conducted by the Royal Navy and Royal Marines during World War II to occupy and deny Iceland to Germany. At the start of the war, Britain imposed strict export controls on Icelandic goods, preventing profitable shipments to Germany, as part of its naval blockade. Britain offered assistance to Iceland, seeking cooperation “as a belligerent and an ally”, but Reykjavik declined and reaffirmed its neutrality. The German diplomatic presence in Iceland, along with the island’s strategic importance, alarmed the British. After failing to persuade the Icelandic government to join the Allies, the British invaded on the morning of 10 May 1940. The initial force of 746 British Royal Marines commanded by Colonel Robert Sturges disembarked at the capital Reykjavík. Meeting no resistance, the troops moved quickly to disable communication networks, secure strategic locations, and arrest German citizens. Requisitioning local transport, the troops moved to Hvalfjörður, Kaldaðarnes, Sandskeið, and Akranes to secure landing areas against the possibility of a German counterattack.

Iceland, an independent sovereign nation ruled by the King of Denmark, joined Denmark in the pursuit of neutrality when the European War began. Upon the German invasion of Denmark in Apr 1940, Icelandic parliament declared King Christian X unable to perform his constitutional duties,

and began to act in a more independent manner, though it remained neutral. On 9 May 1940, the United Kingdom issued a message to Iceland stating her willingness to defend Iceland (Iceland had no military force of her own) if Iceland would allow British forces to establish presence there. The United Kingdom intended to use Iceland to establish a base in the North Atlantic as well as to prevent a German invasion and occupation. The Icelandic government rejected the offer, noting her wish to remain neutral in the conflict. What the Icelandic parliament did not know, however, was that the United Kingdom had been planning an invasion under the code name of Operation Fork since late Apr or early May.

On 3 May 1940, the 2nd Royal Marine Battalion in Bisley, Surrey received orders from London to be ready to move at two hours’ notice for an unknown destination. The battalion had only been activated the month before. Though there was a nucleus of active service officers, the troops were new recruits and only partially trained. There was a shortage of weapons, which consisted only of rifles, pistols, and bayonets, while 50 of the marines had only just received their rifles and had not had a chance to fire them. On 4 May, the battalion received some modest additional equipment in the form of Bren light machine guns, anti-tank guns, and 2-inch mortars. With no time to spare, zeroing of the weapons and initial familiarisation firing would have to be conducted at sea

At 0400 on 8 May, under the command of 49-year-old Colonel Robert Sturges, a highly regarded WW1 veteran, 746 men of the inexperienced 2nd Royal Marine Battalion departed Greenock, Scotland, United Kingdom. Also with the invasion force was a small intelligence team headed by Major Humphrey Quill and a diplomatic mission headed by Charles Howard Smith. In the morning of 10 May, a Walrus aircraft was dispatched to scout the waters leading up to Reykjavík, the capital of Iceland, for German submarine activity.

But mis-communications led to the aircraft circling the actual city several times, thus alerting Icelandic officials the presence of the British force. The acting police chief Einar Arnalds recognized it as a British aircraft, but advised Prime Minister Hermann Jónasson it was probably only a British warship en route on a diplomatic mission. The German consul to Iceland Werner Gerlach was more cautious, who began burning his documents after seeing British warships arrive at the Reykjavík harbor.

As Icelandic officials prepared warning statements for the British fleet announcing their violation of Icelandic neutrality, heavy cruiser HMS Berwick transferred 400 marines to the destroyer Fearless, which took them to Reykjavík.

The invasion was not met with resistance from the 70-strong Reykjavík police force, though a large crowd gathered at the harbor to protest.

The British marines moved to occupy telecommunications facilities, radio stations, and meteorological offices, while the local German population (including Consul Gerlach and crew of German freighter Bahia Blanca) were placed under arrest, all in the attempt to delay the news of the invasion from reaching Germany.In the evening of 10 May, the Icelandic government formally issued a statement noting that their neutrality had been “flagrantly violated” and “its independence infringed”. The British government appeased the protest by promising compensation, trade agreement, non-interference in domestic Icelandic affairs, and the promise that troops would be withdrawn at war’s end.

While the British marines secured Reykjavík,

a small detachment was sent to nearby Hvalfjörður (a fjord), Sandskeið, and Kaldaðarnes. On 15 May, the harbor town of Hafnarfjörður was occupied. On 17 and 19 May, men were sent by ship to land at Akureyri and Melgerði, respectively, in the Eyjafjörður (a fjord) on the northern coast to guard against potential German landings. In the following few weeks, anti-aircraft weapons were deployed in Reykjavík to deter potential German air raids.

When the news of the invasion finally reached Germany, a discussion dubbed Operation Ikarus began to examine the possibility of counter-action, but none came to fruition.

In Jul 1941, the responsibility of the occupation was passed to the United States, which sent 40,000 soldiers to guard the island with a population of merely 120,000.The US had actually not officially joined the War at that stage.

Although Iceland still officially maintained neutrality, she actually cooperated with Allied authorities throughout the war.

The time line

16 Apr 1940 Iceland declared independence from Denmark and asked United States for recognition.

9 May 1940 British troops occupied Iceland.

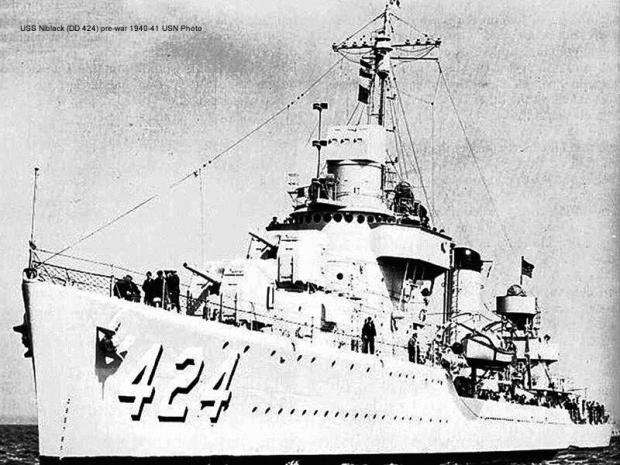

10 Apr 1941 American destroyer USS USS Niblack attacked a German submarine off Iceland; the submarine escaped without being damaged. It was the first shot fired between the US and Germany.

18 Apr 1941 The United States declared that the Pan-American Security Zone, last defined with the 3 Oct 1939 Declaration of Panama, to be extended to 26 degrees west longitude, 2,300 nautical miles east of New York on the east coast of the United States. It was just 50 nautical miles short of Iceland, which was a major Allied convoy staging area.

7 Jul 1941 US Marines who had departed from Naval Station Argentia,with a heavy escort (including battleships New York and Arkansas, cruisers Brooklyn and Nashville, and more than a dozen destroyers)arrived at Reykjavik.

Approximately 230 Icelanders lives were lost in World War II hostilities.Most were killed on cargo and fishing vessels sunk by German aircraft, U-boats or mines

The presence of British,Canadian and American troops in Iceland had a lasting impact on the country. Engineering projects, initiated by the occupying forces – especially the building of Reykjavík Airport – brought employment to many Icelanders. This was the so-called Bretavinna or “Brit labour”. Also, the Icelanders had a source of revenue by exporting fish to the United Kingdom.

There was large-scale interaction between young Icelandic women and soldiers, which came to be known as Ástandið (“the condition” or “situation”) in Icelandic. Many Icelandic women married Allied soldiers and subsequently gave birth to children, many of whom bore the patronymic Hansson (hans translates as “his” in Icelandic), which was used because the father was unknown or had left the country. Some children born as a result of the Ástandið have English surnames.

Trying to find images of the occupation for an article I am writing and I am just wondering where you got them?

LikeLike

Hi Alex, I have them from several sources I found via google and bing, feel free to use my images.

LikeLike

Nice little write up, justone thing,, Iceland declared independance in 1944 not 1940…..

LikeLike

Iceland became a republic in 1944. It had previously been a kingdom sharing a sovereign with Denmark.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on History of Sorts.

LikeLike