Introduction

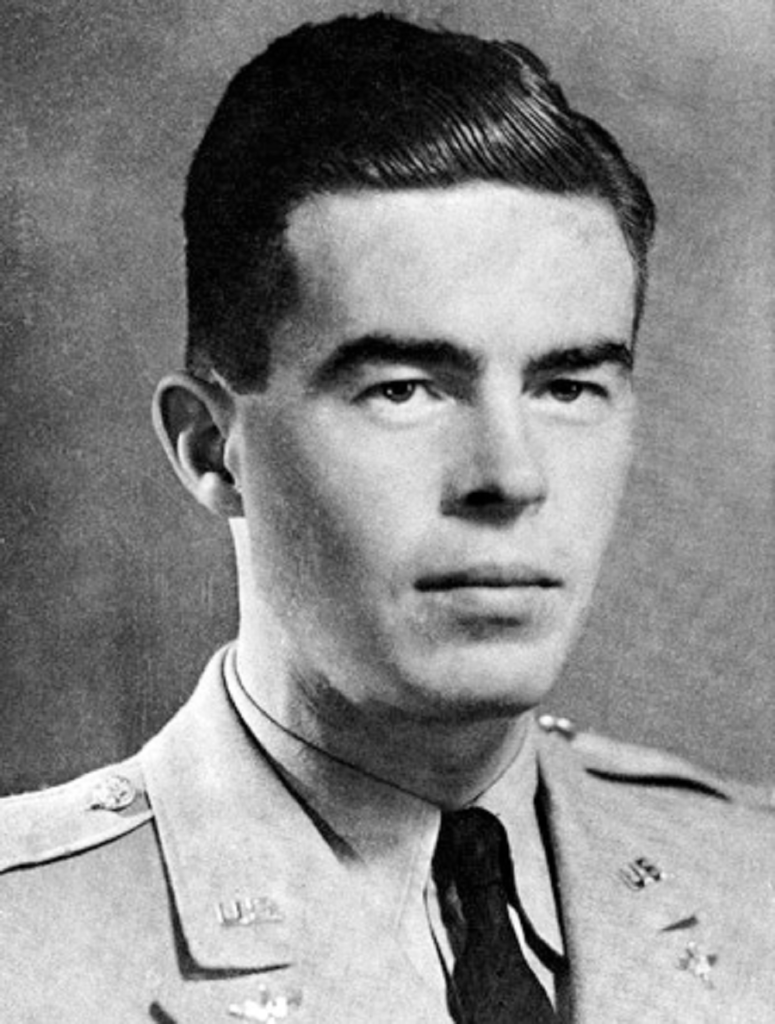

John Morrison Birch (1918–1945) occupies an unusual place in American history. A Baptist missionary turned U.S. Army intelligence officer in China during World War II, his life bridged the spheres of religion, geopolitics, and war. Though he died at just 27 years old, Birch became a symbolic figure in early Cold War discourse when conservative activists portrayed him as the “first American casualty of the Cold War.” His story, however, is more complex than his later appropriation by political movements suggests. Birch’s life illustrates the intersection of faith and wartime service, while his death foreshadowed the U.S.–China estrangement that would dominate much of the 20th century.

Early Life and Missionary Calling

John Birch was born on May 28, 1918, in Landour, India, to missionary parents, but his family soon returned to Georgia in the United States. Raised in a devout Southern Baptist household, Birch demonstrated early intellectual and religious promise. He graduated from Mercer University in 1939 and pursued theological training at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas (Hefley 1989, 27–30). Motivated by a sense of evangelical mission, he volunteered for service in China, arriving in Shanghai in 1940 under the auspices of the Baptist Foreign Mission Board.

In China, Birch quickly distinguished himself by mastering Mandarin and traveling to remote areas to preach. His missionary work unfolded against the backdrop of the Sino-Japanese War, which had already devastated large parts of the country.

World War II and Intelligence Service

The entry of the United States into World War II in December 1941 transformed Birch’s mission. In April 1942, he encountered Colonel Jimmy Doolittle and his crew after their famous raid on Tokyo, assisting them in evading capture by Japanese forces (Tanner 1999, 212–213). Impressed by his linguistic and local knowledge, U.S. officials recruited Birch into the U.S. Army Air Forces and later attached him to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

In his new role, Birch organized guerrilla operations, coordinated supply routes, and gathered intelligence on Japanese movements. Though his work was military in nature, he continued to view it through a spiritual lens, reportedly combining intelligence work with evangelistic efforts (Hefley 1989, 63). Fellow officers remembered him as both courageous and uncompromising, traits that earned him admiration but also tension with colleagues and local allies.

Death and Political Appropriation

On August 25, 1945, less than two weeks after Japan’s surrender, Birch was killed near Xuzhou in Shandong province. Accounts vary, but most agree that a confrontation with Chinese communist soldiers escalated into violence. Birch was shot after refusing to surrender his weapons; his interpreter was also wounded (Hunter 1995, 145–146). His death occurred during the fragile postwar moment when tensions between Chinese Nationalists and Communists were intensifying, foreshadowing the Chinese Civil War and the broader Cold War.

In the years immediately following, Birch was honored by U.S. military authorities for his service but otherwise remained a little-known figure. This changed in 1958, when Robert Welch, a retired businessman and ardent anti-communist, founded the John Birch Society. Welch declared Birch the “first casualty of the Cold War,” using his story to symbolize the global struggle against communism (Diamond 1995, 45). The society became controversial for its conspiratorial worldview, but its adoption of Birch’s name ensured that his legacy would be tied to Cold War politics rather than his missionary or military career.

Legacy and Historical Interpretation

Historians have emphasized the distinction between Birch the individual and Birch the symbol. As Hunter (1995) argues, Birch himself was primarily motivated by faith and patriotism, not ideology. His posthumous appropriation reflected the anxieties of Cold War America more than his own convictions. To his contemporaries in China, Birch was a missionary with unusual courage and zeal; to later activists, he became a martyr of anti-communism.

Today, Birch’s story serves as a reminder of how individuals can be reinterpreted to meet the needs of political movements. His life highlights the complex relationship between religion and American foreign policy, particularly in China, where missionaries often blurred the lines between spiritual and political engagement. His death underscores the volatility of China in 1945, where shifting alliances and rising communist power would soon redraw global lines of conflict.

John Morrison Birch’s life and death embody the intertwining of faith, war, and ideology in the 20th century. As a missionary, he sought to spread Christianity in wartime China; as a soldier, he used his talents in service of the Allied cause. His violent death at the hands of communist soldiers marked the beginning of a new geopolitical era, even if he did not live to see it. While his name was later appropriated by political activists, the real Birch was a figure of conviction and sacrifice, whose legacy remains more nuanced than the Cold War symbol he became.

References

Diamond, Sara. Roads to Dominion: Right-Wing Movements and Political Power in the United States. New York: Guilford Press, 1995.

Hefley, James C. The Secret File on John Birch. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1989.

Hunter, Edward. The John Birch Controversy. New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1995.

Tanner, Harold M. Where Chiang Kai-shek Lost China: The Liao-Shen Campaign, 1948. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999.

sources

https://ww2db.com/person_bio.php?person_id=346

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Birch_(missionary)

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment