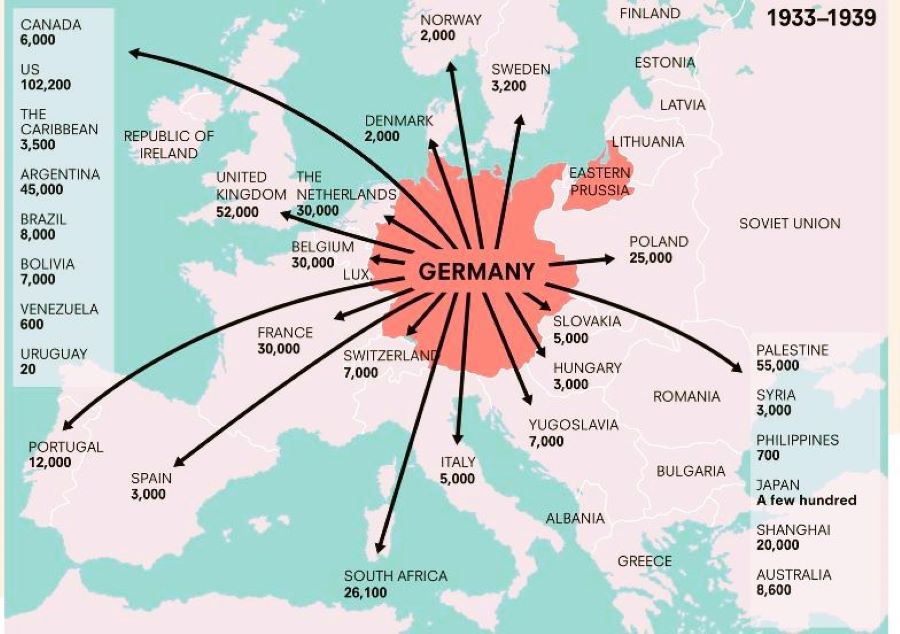

I often hear the argument, “Why did the Jews not simply leave Germany when Hitler got to power?” It was just not as simple as that. Many German and Austrian Jews saw themselves as German or Austrian first, and they considered themselves to be part of society. Why would they leave their homes and their possessions when they hadn’t done anything wrong?

For those who did want to escape the Nazi regime, there were a significant number of obstacles to overcome. In the 1930s, very much like the 2020s, refugees just weren’t welcome in other countries.

The period from 1933 to 1942 was marked by the escalating persecution of Jews under the Nazi regime, culminating in the Holocaust. As the Nazi grip on power tightened, many Jews sought to escape the increasingly hostile environment. However, Jewish emigration during this period was fraught with immense challenges, including restrictive immigration policies, financial burdens, bureaucratic obstacles, and growing global anti-Semitism. These factors combined to make escape difficult, if not impossible, for many Jews, leading to the tragic fate of millions during the Holocaust.

When Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933, the situation for Jews rapidly deteriorated. The Nazis enacted a series of anti-Jewish laws, beginning with the 1933 boycott of Jewish businesses and culminating in the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which stripped Jews of their citizenship and fundamental rights. The state-sponsored violence of Kristallnacht in November 1938 further demonstrated the deadly intent of the Nazi regime. These events led to a growing sense of urgency among Jews to flee Germany and the territories it would soon occupy.

Despite the increasing dangers, Jewish emigration faced formidable obstacles. The most significant challenge was the restrictive immigration policies of many countries, including the United States, Britain, and various European nations. The global economic depression of the 1930s led to rising unemployment and increased xenophobia, resulting in stricter immigration controls. Countries feared that an influx of Jewish refugees would exacerbate economic problems and strain social services. For instance, the United States, under the 1924 Immigration Act, had strict quotas that severely limited the number of immigrants, including Jews, from Eastern and Southern Europe.

Despite the enormous difficulties, 120,000 Jews still managed to leave Germany in 1938 and 1939; of the approximately 185,000 Jews remaining, about 18,000 to 20,000 managed to leave the country when the Second World War broke out.

The Evian Conference of 1938, convened by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, starkly highlighted the reluctance of the international community to accept Jewish refugees. Delegates from 32 countries expressed sympathy for the Jews but offered little concrete assistance. The Dominican Republic was the only country willing to accept a significant number of Jewish refugees, while other nations, including the United States and Britain, maintained their restrictive immigration policies. The conference was a clear indication that the world was unwilling or unable to provide refuge for the Jews fleeing Nazi persecution.

In addition to restrictive immigration policies, Jews faced considerable financial and bureaucratic hurdles in their efforts to emigrate. Many countries require potential immigrants to provide proof of economic self-sufficiency, including affidavits of support from residents or significant sums of money deposited in local banks. For many Jews, who Nazi policies had economically marginalized, such requirements were impossible to meet. The Nazis had also imposed “flight taxes” and seized Jewish assets, leaving many without the means to finance their escape.

Even when Jews managed to secure the necessary funds, obtaining the required visas and travel documents was an arduous process. Visa applications often require extensive paperwork, including proof of identity, police certificates, and medical exams, which could take months or even years to process. The shifting geopolitical landscape further complicated the bureaucracy, as countries annexed or occupied by Germany, such as Austria and Czechoslovakia, saw their Jewish populations face immediate threats and escalating barriers to escape.

Anti-Semitism also played a significant role in limiting Jewish emigration. Many countries, particularly in Eastern Europe, harbored deep-seated anti-Jewish sentiments that influenced their immigration policies. Public opinion in countries like the United States was not uniformly sympathetic to the plight of Jewish refugees, and anti-Semitic attitudes contributed to the reluctance to relax immigration restrictions. In Britain, fears of provoking Nazi Germany and anti-Jewish sentiments within the government also curtailed efforts to rescue Jewish refugees.

As the Nazi regime expanded its control over Europe, the window of opportunity for Jewish emigration rapidly closed. The invasion of Poland in 1939 and the subsequent outbreak of World War II marked a turning point. With the establishment of ghettos and the onset of mass deportations, escape became increasingly difficult. By 1941, with the implementation of the “Final Solution,” the systematic extermination of Jews was underway, and emigration was virtually impossible. Even those who managed to flee to neighboring countries often found themselves trapped once Nazi forces occupied those territories.

The Madagascar Plan

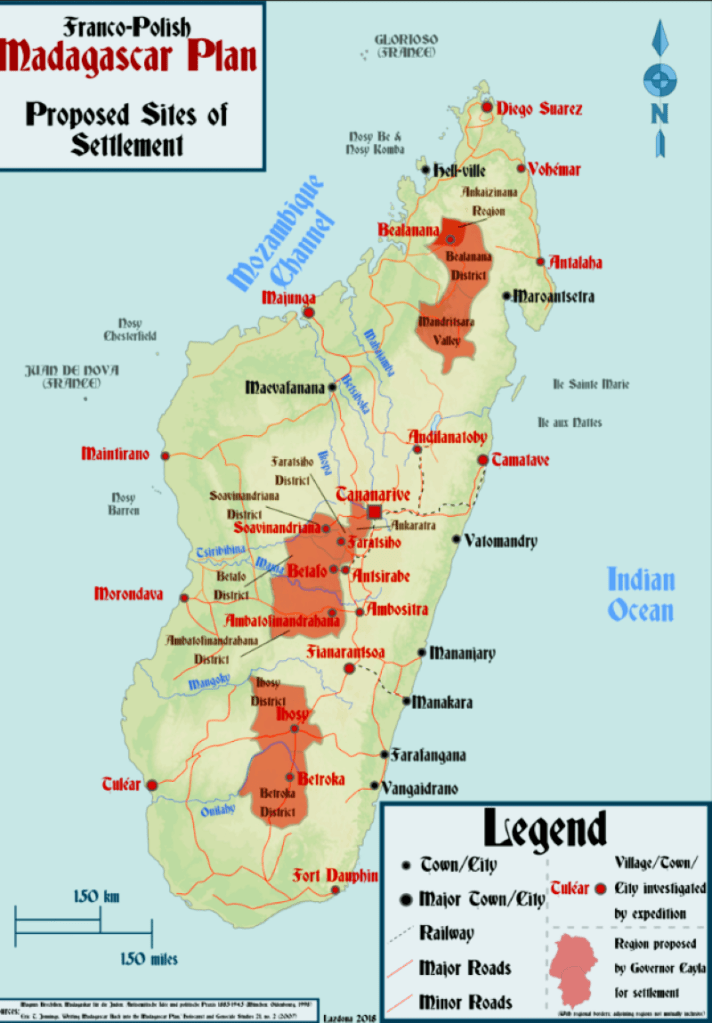

The Madagascar Plan was a proposal made by Nazi Germany during World War II to forcibly relocate the Jewish population of Europe to the island of Madagascar. The conceived plan was the solution to what the Nazis referred to as the “Jewish Question,” a euphemism for their broader goal of eliminating Jewish presence in Europe.

Origins and Development

The idea of relocating Jews to Madagascar predates the Nazis, with some versions of the concept emerging as early as the 19th century. However, it gained severe consideration under the Nazi regime. The plan was primarily developed by the SS (Schutzstaffel), led by Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich, in 1940, shortly after Germany’s victory over France. France controlled Madagascar at the time, and the Nazis believed they could seize the island and use it as a remote ghetto for European Jews.

Key Features of the Plan

- Relocation of Jews: The plan envisioned the deportation of up to four million Jews from Europe to Madagascar. The SS intended for the Jews to be governed by the Nazi-controlled SS police, effectively making the island a giant ghetto.

- Conditions and Logistics: The Nazis expected the harsh conditions on the island—poor climate, lack of infrastructure, and isolation—to lead to high mortality rates among the Jewish population, a form of indirect extermination.

- Abandonment: The plan was ultimately never implemented. By 1942, the Nazi regime had decided on the “Final Solution,” which involved the mass extermination of Jews in concentration and extermination camps across Europe. This shift was due to logistical challenges and the changing dynamics of the war, particularly after Germany invaded the Soviet Union.

Historical Significance

The Madagascar Plan is significant as it highlights the evolution of Nazi anti-Semitic policies. While the Nazis did not carry out the plan, it demonstrated the lengths to which the Nazi regime was willing to go to rid Europe of Jews. The shift from forced emigration and relocation to genocide marks a grim turning point in the history of the Holocaust.

In summary, the Madagascar Plan is a chilling example of Nazi intentions regarding the Jewish population, a prelude to the horrific realities of the Holocaust that followed.

The Germans weren’t the only ones who wanted to relocate the Jews to Madagascar.

1937 French Polish proposal

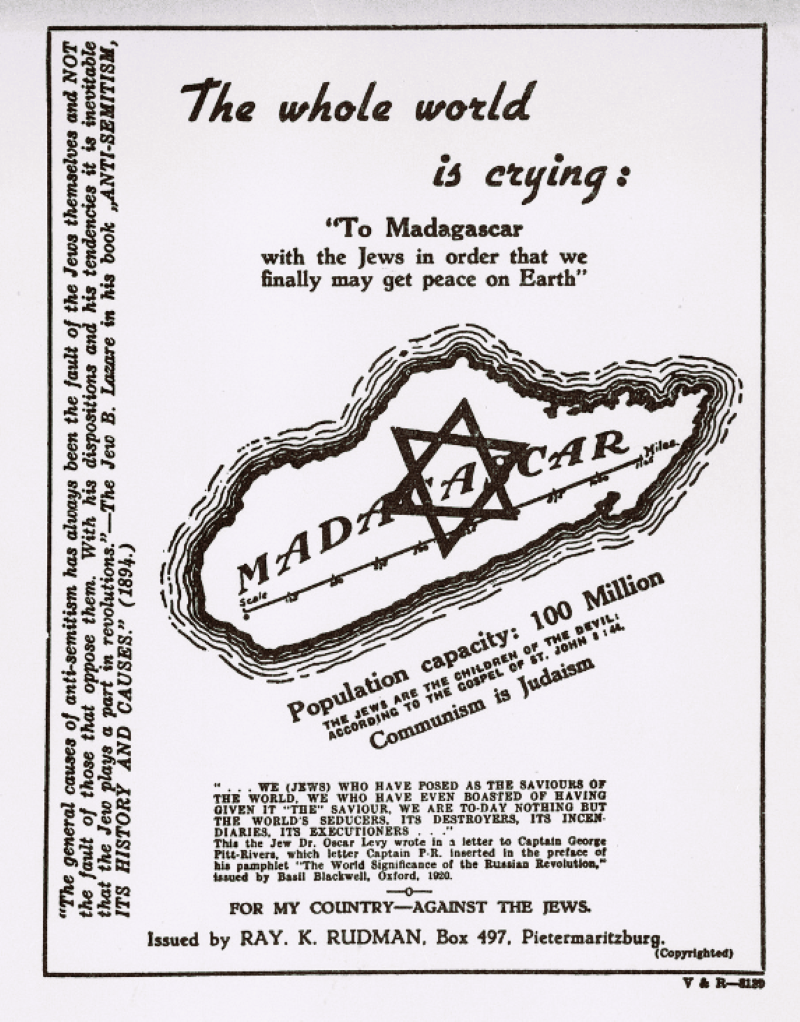

An anti-semitic flier below was issued in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, claiming that Jews are responsible for communism and should go to Madagascar. (I don’t know when it was issued, circa 1940.)

The plan detailed the resettlement of a million Jews per year for four years, to the island that was to be policed by the SS. The plan was cancelled in 1942 with the commencement of the Final Solution.

The plan detailed the resettlement of a million Jews per year for four years to the island that was to be policed by the SS. The Nazis canceled the plan in 1942 with the commencement of the Final Solution.

Sources

https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1154151

https://www.jns.org/column/antisemitism/23/9/3/315690/

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/antisemitism-in-history-nazi-antisemitism

https://www.annefrank.org/en/anne-frank/go-in-depth/impossibilities-escaping-1933-1942/

https://www.bbc.com/news/explainers-61782866

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment