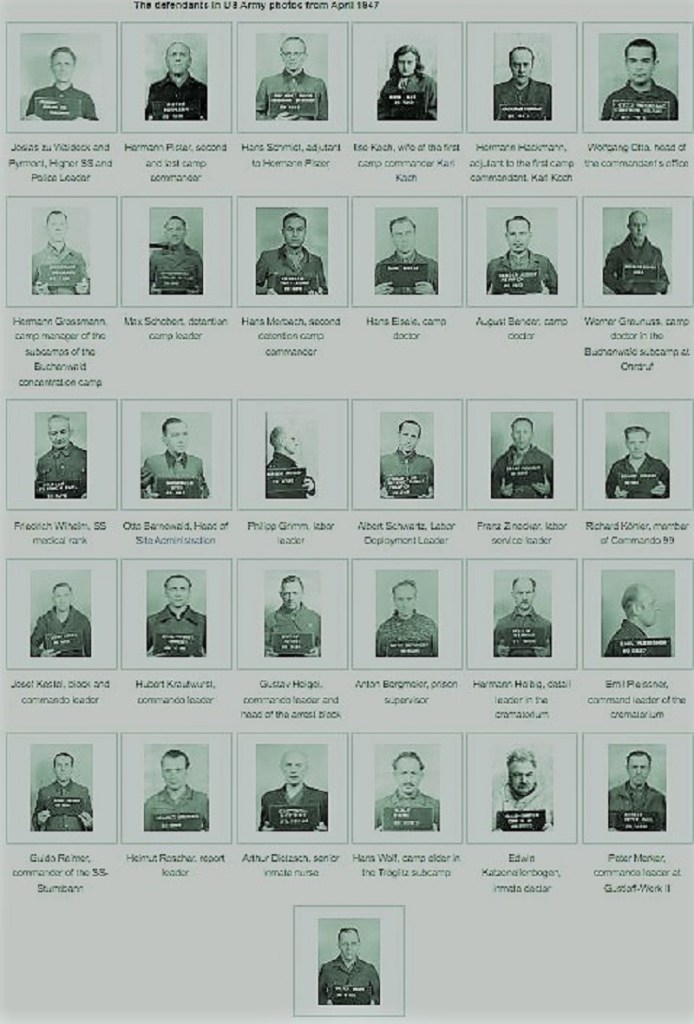

The Buchenwald Trial was a war crime trial conducted by the United States Army as a court-martial in Dachau, then part of the American occupation zone. It took place from 11 April to 14 August 1947.

On 14 August 1947, the Buchenwald main trial United States of America vs. Josias Prince of Waldeck et al. ended. All 31 accused were found guilty of war crimes in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp and its satellite camps—22 were sentenced to death. Ilse Koch, the only woman in the dock, received a life sentence. Former prisoners accused her of being particularly sadistic. However, because she was pregnant when the verdict was announced—the court waived the death penalty.

Ilse Koch wasn’t only considered sadistic by the Buchenwald prisoners but also by the Nazis. On 17 August 1944, SS judge Konrad Morgen formally charged Ilse’s husband, Karl Koch, with the “embezzlement and concealing of funds and goods in an amount of at least 200,000 RM,” and the “premeditated murder” of three inmates, ostensibly to prevent them from giving evidence to the SS investigatory commission. Ilse was charged with the “habitual receiving of stolen goods, and taking for her benefit at least 25,000 RM…” While Ilse Koch was acquitted at the subsequent SS trial in December 1944, Konrad Morgen described her as “a hussy who rode on horseback in sexy underwear in front of the prisoners and then noted down for punishment the numbers of those who looked at her.”

Aside from Ilse Koch, most of the accused were members of the former camp staff, but also the Higher SS and Police Leader (HSSPF) Josias zu Waldeck und Pyrmont, who was responsible for the Buchenwald concentration camp. In addition, the camp commandant Hermann Pister and members of the commandant’s staff.

Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck und Pyrmont: Life Imprisonment (Commuted to 20 Years Imprisonment)

Ilse Koch: Life Imprisonment (Commuted to 4 Years Imprisonment)

Hermann Pister: Death Sentence (Died In Prison on the 28 September 1948)

SS Dr Hans Eisele: Death Sentence (Sentenced in Absentia)

August Bender: 10 Years Imprisonment (Commuted to 3 Years Imprisonment)

Kapo Hans Wolf: Death Sentence (Executed on the 19 November 1948)

Werner Greunuss: Life Imprisonment (Commuted to 20 Years Imprisonment)

Helmut Roscher: Death Sentence (Commuted to Life Imprisonment)

Franz Zinecker: Life Imprisonment

Phillip Grimm: Death Sentence (Commuted to Life Imprisonment)

Hubart Krautwurst: Death Sentence (Executed on the 26 November 1948)

Emil Pleissner: Death Sentence (Executed on the 26 November 1948)

Albert Schwartz: Death Sentence (Commuted to Life Imprisonment)

Hans Merbach: Death Sentence (Executed on the 14 January 1949)

Friedrich Wilhelm: Death Sentence (Executed on the 26 November 1948)

Hermann Hackmann: Death Sentence (Commuted to Life Imprisonment)

Dr Edwin Katzenellenbogen: Life Imprisonment (Commuted to 12 Years Imprisonment)

Wolfgang Otto: 15 Years Imprisonment

Hans – Theodor Schmidt: Death Sentence (Executed on the 7 June 1951)

Gustav Heigel: Death Sentence (Commuted to Life Imprisonment)

Quido Reimer: Death Sentence (Commuted to Life Imprisonment)

Richard Köhler: Death Sentence (Executed on the 26 November 1948)

Max Schobert: Death Sentence (Executed on the 19 November 1948)

Kapo Dr Arthur Dietzsch: 15 Years Imprisonment

Hermann Helbig: Death Sentence (Executed on the 19 November 1948)

Walter Wendt: 15 Years Imprisonment (Commuted to 5 Years Imprisonment)

Hermann Grossmann: Death Sentence (Executed on the 19 November 1948)

Peter Merker: Death Sentence (Commuted to 20 Years Imprisonment)

Josef Kestel: Death Sentence (Executed on the 19 November 1948)

Anton Bergmeier: Death Sentence (Commuted to Life Imprisonment)

Otto Barnewald: Death Sentence (Commuted to Life Imprisonment)

Peter Zenkle, a former prisoner at Buchenwald, said the following about the camp, “The pigs in the SS stables received better feed than the inmates were fed.”

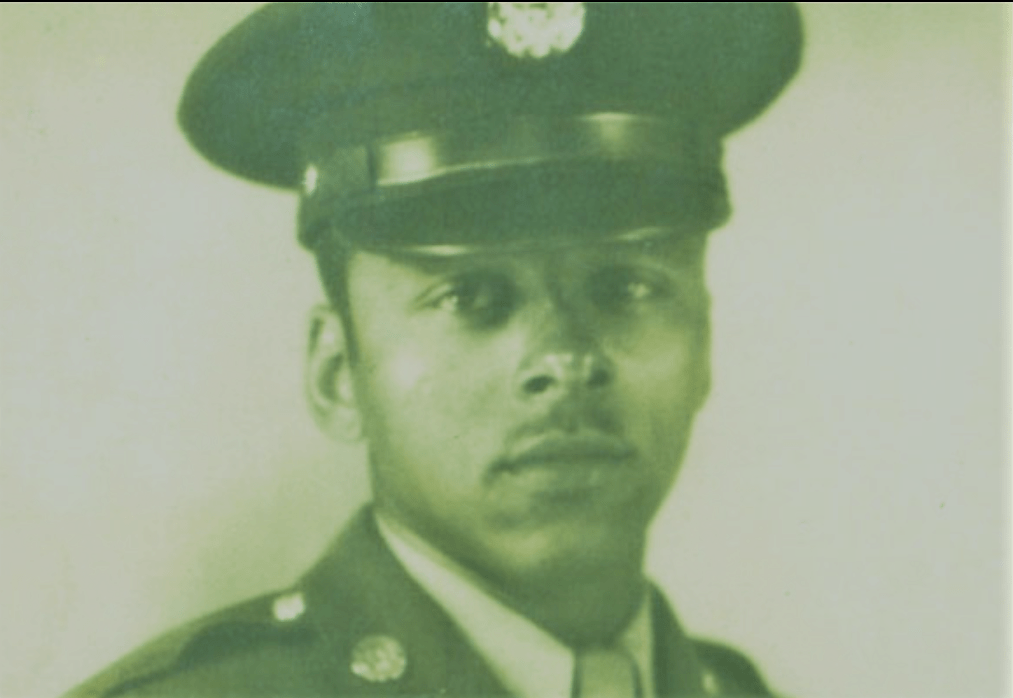

Leon Bass, an African-American soldier, described his experiences entering the Buchenwald concentration camp in April 1945.

“I was sent as part of a liaison group to see if we could arrange for a campsite for our unit. And we arrived in this place called Weimar and drove out to, what I found out now, was to be a concentration camp. And I didn’t know anything about concentration camps. So when the officer told us to follow him and get on the trucks, I did ask him…I said, ‘Where are we going?’ And he said, ‘We’re going to a concentration camp.’

I really was puzzled because I didn’t know a thing about that. No one had ever mentioned it in all the training I received. But on this day, in April 1945, I was going to have the shock of my life. Because I was going to walk through the gates of a concentration camp called Buchenwald. And you got to believe me when I tell you I wasn’t ready for that. I was totally unprepared for that kind of experience.

But you see, I can never, I can never forget that day because when I walked through that gate, I saw in front of me what I call the walking dead. I saw human beings, human beings that had been beaten, had been starved, they’d been tortured. They’d been denied everything, everything that would make anyone’s life livable.

They were standing in front of me and they were skin and bone. They had skeletal faces with deep-set eyes. Their heads had been clean-shaved, and they were standing there, and they were holding on to one another just to keep from falling. Many of them had sores on their bodies. And I can remember this so vividly, sores that came from malnutrition. One man held out his hands, and his fingers had webbed together with the scabs that had come from the sores brought on by the malnutrition.

Oh, my God, I’d seen nothing like this in all my life, nothing. But when they started to move, stumbling forward toward me, I backed away. Oh, I backed up and I stopped. And I said to myself, my God, my God, what is all this insanity? Who are these people? And furthermore, what have they done that was so terrible that would cause anybody to treat them like this? And you see, I didn’t know really, I didn’t know.

But there was this young man who spoke English and he began to tell us about Buchenwald. And he said that these people were Jews, they were Gypsies, they were Jehovah’s Witnesses, and there were some Catholics. There were trade unionists, communists, and homosexuals. Oh, he went on and on. He listed so many different groups that had been placed in the camp. And I knew, that in my judgment, the Nazis had placed them there because the Nazis were saying none of them were good enough, therefore, they were not fit to live. They could be terminated—murdered. Man, I couldn’t get a handle on this. This was beyond anything in my experience.

But I walked about the camp. I went to a place where the men would sleep—they called it a barrack—and I opened the door, I stepped back across the threshold, and I closed the door. But I could go no further. You see that odour, the stench, that comes from death and human waste—well, it was overpowering. It was awesome. I stood there and I was holding my breath all the time. I was holding my breath, and I was going to leave. I knew I couldn’t stay.

And so I turned, but before I could step away, I looked down. And there, on the bottom bunk near the door, was a man. Oh, he was an emaciated—that person. He was skin and bone. He was on a bed of filthy straw and rags. And he was trying so desperately to look at me with that skeletal face and those deep-set eyes, but he was so weak. You see, the man had been starved for so long, and it was a struggle for him just to look at me. But finally he did. He looked up at me and he said nothing. Nor did I. So now, I opened the door, stepped across the threshold, and closed the door.

I was going to walk away from that place but another man came by. He was– oh, he was skin and bone. And he stopped right there in front of me. He undid what was holding his trousers, he let them fall, he squatted down, and he began to defecate right in front of me. And I couldn’t believe this. Oh, he was so thin, it looked like the bones of his buttocks would come through the skin. But I stood there saying, no, no. You don’t do this in public. Where’s your dignity?

But you see, that was my hang-up. I was hung up on something called dignity when that man was merely trying to survive. He wanted to live. I didn’t know.”

In the decades that followed, the crimes committed in Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora were tried before courts in both Germanys and abroad. Yet even if some of these trials were quite sensational, most of the judicial inquiries were ultimately dropped without results.

Of the thousands of SS men and women overseers who had served in Buchenwald, Mittelbau-Dora and their subcamps, only a small fraction were brought to trial. The persons who had participated in the countless crimes against concentration camp inmates in the weeks before the end of the war were likewise almost never prosecuted.

sources

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/index.php/content/en/artifact/buchenwald-trial-document

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/buchenwald-war-crimes-trials

https://liberation.buchenwald.de/en/otd1945/criminal-prosecution

https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/eyewitness-buchenwald

Leave a comment