Very few people will dispute that Abraham Lincoln was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, US President. However, his moral values weren’t as pure as many people think they were.

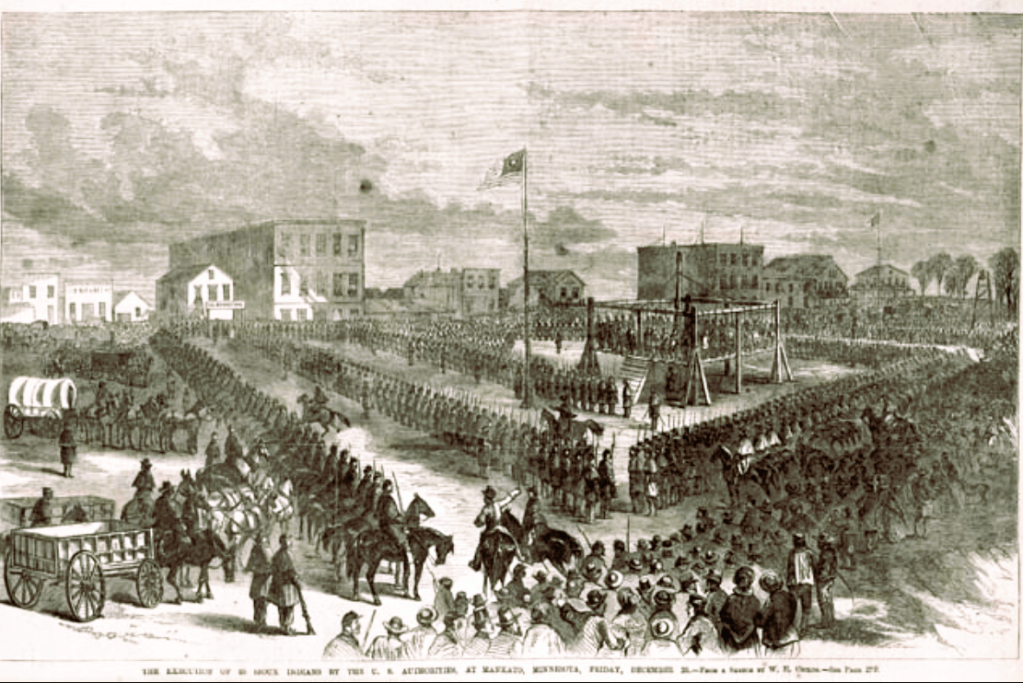

Thirty-eight Native Americans were hanged on Dec. 26, 1862, as ordered by President Abraham Lincoln, on December 6, 1862, after the 1862 Dakota War, which was also known as the Sioux Uprising of 1862. The sentences of 265 others were commuted.

The Santee Sioux were found guilty of joining in the so-called “Minnesota Uprising,” which was actually part of the broader Indian wars that occurred throughout the West during the second half of the nineteenth century. For nearly half a century, Anglo settlers invaded the Santee Sioux territory in the Minnesota Valley, and government pressure gradually forced the Native peoples to relocate to minor reservations along the Minnesota River.

At the reservations, the Santee were severely mistreated by corrupt Federal Indian agents and contractors; during July 1862, the agents pushed the Native Americans to the brink of starvation by refusing to distribute stores of food because they had not yet received their customary kickback payment.

On September 28, 1862, two days after the surrender at Camp Release, a commission of military officers established by Henry Sibley began trying Dakota men accused of participating in the war. Several weeks later, the trials were moved to the Lower Agency, where they were held in one of the only buildings left standing, trader François LaBathe’s summer kitchen.

As weeks passed, cases were handled with increasing speed. On November 5, the commission completed its work. 392 prisoners were tried, 303 were sentenced to death, and 16 were given prison terms.

President Lincoln and government lawyers then reviewed the trial transcripts of all 303 men. As Lincoln would later explain to the U.S. Senate:

“Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on the one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, I ordered a careful examination of the records of the trials to be made, in view of first ordering the execution of such as had been proved guilty of violating females.”

When only two men were found guilty of rape, Lincoln expanded the criteria to include those who had participated in “massacres” of civilians rather than just “battles.” He then made his final decision and forwarded a list of 39 names to Sibley.

At 10:00 am on December 26, 38 Dakota prisoners were led to a scaffold specially constructed for their execution. One had been given a reprieve at the last minute. An estimated 4,000 spectators crammed the streets of Mankato and surrounding land. Col. Stephen Miller, charged with keeping the peace in the days leading up to the hangings, had declared martial law and had banned the sale and consumption of alcohol within a ten-mile radius of the town.

As the men took their assigned places on the scaffold, they sang a Dakota song as white muslin coverings were pulled over their faces.

Drumbeats signaled the start of the execution. The men grasped each others’ hands. With a single blow from an ax, the rope that held the platform was cut. Capt. William Duley, who had lost several members of his family in the attack on the Lake Shetek settlement, cut the rope.

After dangling from the scaffold for a half hour, the men’s bodies were cut down and hauled to a shallow mass grave on a sandbar between Mankato’s main street and the Minnesota River. Before morning, most of the bodies had been dug up and taken by physicians for use as medical cadavers.

After the execution, it was discovered that two men had been mistakenly hanged. The Minnesota Historical Society reports that “Wicaƞḣpi Wastedaƞpi (We-chank-wash-ta-don-pee), who went by the common name of Caske (meaning first-born son), reportedly stepped forward when the name ‘Caske’ was called, and was then separated for execution from the other prisoners. The other, Wasicuƞ, was a young white man who had been adopted by the Dakota at an early age. Wasicuƞ had been acquitted.

Although Abraham Lincoln opposed slavery, his in-laws were slave owners, albeit reluctant.

Lincoln, the politician, did not recognize blacks as his social or political equals, and his opinion on this did not change during his years as a lawyer and office seeker living in Illinois. Lincoln was opposed to the institution of slavery during his entire lifetime, but, like most white Americans, he was not an abolitionist. In antebellum America, abolitionists were a marginal, radical group, and most white Americans did not participate in or endorse abolitionist activities.

He was a man of contradictions, but this probably is what made him the great leader he became.

Sources

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2206706

https://apnews.com/article/archive-fact-checking-2786870059

https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/abraham-lincoln/

https://www.usdakotawar.org/history/aftermath/trials-hanging

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment