Fascism, a political ideology that rose to prominence in Europe during the early 20th century, left deep imprints on the history of several countries, from Mussolini’s Italy to Hitler’s Germany and Franco’s Spain. In Ireland, however, fascism remained a relatively marginal movement, confined to small groups and figures that never gained mass political support. Yet, Irish fascism was a significant part of the political landscape during the interwar period, influenced by European trends and shaped by Ireland’s own nationalist struggles and Catholic conservatism. This essay examines the history, ideology, and limited impact of Irish fascism, focusing on key movements like the Blueshirts, Ailtirí na hAiséirghe, and the role of prominent figures such as Eoin O’Duffy.

Origins and Early Development: The Blueshirts

Irish fascism found its first significant expression in the Army Comrades Association (ACA), more commonly known as the Blueshirts, in the early 1930s. The Blueshirts emerged in response to the political turbulence of post-independence Ireland. Formed initially as a veterans’ organization to protect conservative interests, particularly the supporters of the pro-Treaty Cumann na nGaedheal party, the Blueshirts quickly transformed into a paramilitary group with fascist overtones.

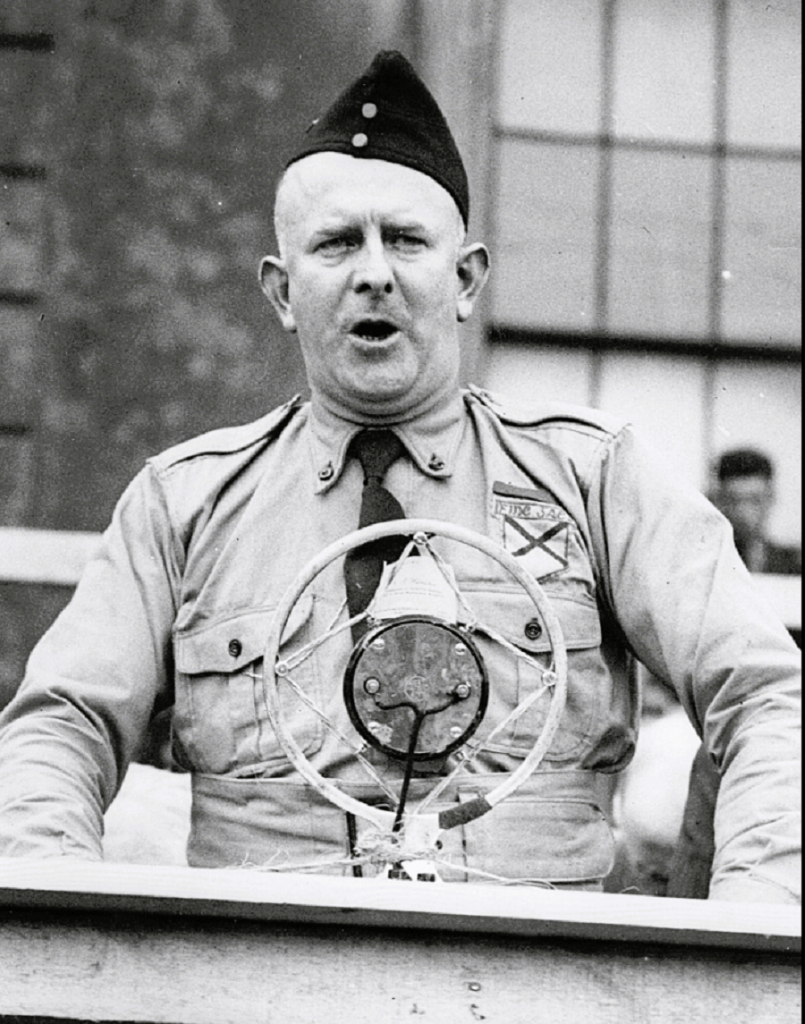

Under the leadership of General Eoin O’Duffy, a former Garda (police) commissioner and an influential figure in the Irish War of Independence, the Blueshirts adopted a platform that reflected European fascist ideologies, particularly those of Mussolini.

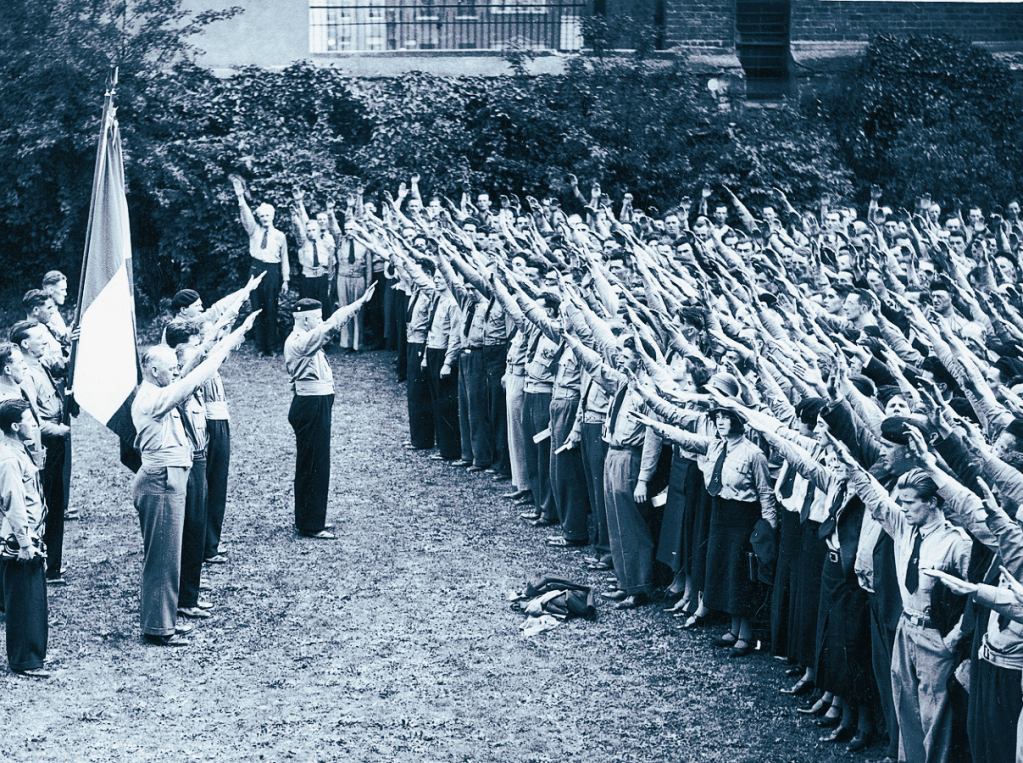

The group wore blue shirts as a uniform, engaged in street confrontations with republican and communist groups, and adopted fascist-style salutes. Their aims were to restore “order” in Ireland and resist the newly elected Fianna Fáil government, which they viewed as a threat to the stability of the Irish Free State. O’Duffy and his followers also claimed to be defenders of Catholicism and Irish nationalism, tapping into conservative fears of communism and social upheaval.

However, despite the visibility of the Blueshirts and their paramilitary aesthetics, their political ambitions were thwarted. O’Duffy’s attempt to organize a “March on Dublin”—an imitation of Mussolini’s March on Rome—was banned by the government, and the movement failed to gain significant popular support. In 1933, the Blueshirts merged into the newly formed Fine Gael party, which quickly abandoned the more extreme aspects of fascism and embraced parliamentary democracy. Thus, the Blueshirts’ flirtation with fascism, while notable, was short-lived and politically limited.

Eoin O’Duffy and the National Corporate Party

Despite the failure of the Blueshirts, Eoin O’Duffy continued to pursue fascist ideals in the following years. In 1935, he founded the National Corporate Party, a more explicitly fascist organization that promoted the establishment of a corporatist state in Ireland. This vision was based on Mussolini’s model, where different sectors of society—business, labor, and agriculture—would be organized into state-controlled entities, thereby replacing the democratic system with authoritarian governance.

O’Duffy’s vision of an authoritarian Ireland aligned with many of the same themes that characterized European fascism: anti-communism, nationalism, and a deep desire to suppress political dissent. His actions during this period also reflected his international ambitions. In 1936, O’Duffy led a brigade of Irish volunteers to fight for Franco’s Nationalist forces during the Spanish Civil War. He saw the war as a critical front in the global struggle against communism and atheism, linking Irish fascism to broader European conflicts.

Despite these efforts, O’Duffy’s political movement failed to garner substantial support. The National Corporate Party was short-lived, and O’Duffy’s once-prominent status in Irish politics diminished. His personal leadership and ideological pursuits did not translate into a mass movement, largely because the social and political climate in Ireland was not conducive to fascism.

Ailtirí na hAiséirghe: The Architects of Resurrection

Another key chapter in the history of Irish fascism was the formation of Ailtirí na hAiséirghe (Architects of the Resurrection) in 1942, led by Gearóid Ó Cuinneagáin.

This movement was perhaps the most ideologically extreme of Ireland’s fascist groups. Ailtirí na hAiséirghe sought to create a totalitarian Irish state based on fascist principles, glorifying Irish Gaelic identity, Catholicism, and authoritarian rule. They envisioned a corporatist state similar to Mussolini’s Italy but infused with a uniquely Irish brand of nationalism and traditionalism.

Ó Cuinneagáin’s party advocated for a radical cultural revival that would restore Ireland’s Gaelic heritage and Catholic social values. They also promoted a vision of Irish territorial expansion, aiming to unify Ireland by force and reclaim parts of the United Kingdom, particularly Northern Ireland. At the same time, Ailtirí na hAiséirghe harbored sympathies for Nazi Germany, and their rhetoric echoed European fascist movements in its emphasis on militarism and the glorification of the state.

However, like other fascist movements in Ireland, Ailtirí na hAiséirghe failed to attract widespread support. While it maintained a small but loyal following, the party’s vision of authoritarianism and expansionism was out of step with the majority of Irish society. By the 1950s, the movement had faded into obscurity.

Why Did Fascism Fail in Ireland?

Several factors explain why fascism remained a fringe movement in Ireland and never gained the same foothold as it did in countries like Italy, Germany, or Spain.

- Irish Nationalism and Anti-Imperialism: The primary focus of Irish nationalism throughout the early 20th century was on achieving independence from British rule. Irish political discourse was dominated by anti-imperialist sentiment, which did not easily align with the imperialist or militaristic aspirations of fascism. The republican movement, particularly through Sinn Féin and the IRA, emphasized popular sovereignty and anti-authoritarianism, leaving little room for fascist ideology to take root.

- Fianna Fáil and Éamon de Valera: The success of the Fianna Fáil party under Éamon de Valera played a significant role in stifling the growth of fascism. De Valera’s government, which embraced Catholic social values and conservative nationalism, appealed to many of the same segments of society that fascist movements targeted. As Fianna Fáil became the dominant political force, it absorbed much of the political energy that might have fueled more radical movements.

- The Role of the Catholic Church: While fascist movements in Ireland often claimed to defend Catholic values, the Irish Catholic Church did not actively support fascism. Ireland’s deeply religious society was conservative but not inclined toward the kind of revolutionary or authoritarian nationalism that characterized fascism in other parts of Europe.

- Economic and Political Stability: Unlike countries such as Germany or Italy, Ireland did not experience the same level of political or financial crisis that often fueled the rise of fascism. While Ireland had its struggles, the absence of a severe national emergency made it harder for extremist movements to gain traction.

Fascism in Ireland, while never a dominant force, was a noteworthy aspect of the country’s political landscape during the interwar period. Movements like the Blueshirts and Ailtirí na hAiséirghe reflected the influence of European fascism. Still, their failure to attract mass support highlighted the unique conditions of Irish society. The combination of a strong tradition of anti-imperialist nationalism, the dominance of Fianna Fáil, the influence of Catholic conservatism, and relative political stability ensured that fascism remained on the margins of Irish politics. Today, the legacy of Irish fascism is largely a historical curiosity, overshadowed by the broader narrative of Ireland’s fight for independence and its complex relationship with nationalism and democracy. However, the rhetoric of the current Taoiseach(prime minister), Simon Harris (Fine Gael), towards Israel seems to be reminiscent of the maiden speech of Oliver J Flanagan, a former Fine Gael politician, in the Dail (Irish parliament) on July 9, 1943.

“I cannot for the life of me see why those men should be interned because of their views. Their views are the views of Wolfe Tone, or Pearse, and of Connolly. Deputy Dillon, a member of this House, says that this nation should be at war with England—that it should join in with her. Senator MacDermot, a member of the Oireachtas, in a broadcast from the United States some time ago said: “Shame on Ireland because she is not in the war with England, her best friend and ally.” That man was one of Taoiseach’s nominees for the Seanad. I wonder he will appear on his list for the Seanad this time? There was no Act to intern Deputy Dillon and no order to arrest Senator MacDermot the moment he arrived here. I am surprised to see Deputy Dillon free because if I said the things that he had said, I would have been in jail long ago. The Guards in Mountrath tried to put me in jail. They had no case against me or I would be there.

I want to ask that the Emergency Powers Order, which prevents the division of land from taking place, be immediately lifted. The Minister for Lands wrote me some time ago to say that there was not sufficient staff in the Land Commission to deal with the division of land. How is it that there are thousands of well-educated young men being forced to take the emigrant ship, not from Galway Bay or Cobh this time to take them to the greater Ireland beyond the Atlantic, but to take them from Dun Laoghaire and Rosslare to the land beyond the Irish Sea, the land of our traditional enemy, to help England in her war effort against Germany? There is one thing that Germany did, and that was to rout the Jews out of their country. Until we rout the Jews out of this country, it does not matter a hair’s breadth what orders you make. Where the bees are, there is the honey, and where the Jews are, there is the money. I do not propose to detain the House further. I propose to vote against such Orders and actions, and I am doing so on Christian principles. The Minister for Justice could not give me a straight answer a few moments ago. I am sorry that I interrupted him in the heat of the discussion. Of course, one needs great patience to listen to what is going on. I know very well that even the clergy in the Minister’s constituency are up against him.

Father Keane, the parish priest of Athleague, is up against him, and when the clergy are up against him, surely it will be hard for any of us to support him. I thank the Chair for allowing me to make my statement.”

Sources

https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1943-07-09/8/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/261053

https://rupture.ie/articles/irish-fascism-a-very-short-introduction-part-one-1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gear%C3%B3id_%C3%93_Cuinneag%C3%A1in

Leave a comment