The concept of concentration camps did not originate with the Nazis. In fact, the British created the first concentration camps during the Boer War (1899–1902). These camps were used to detain Boers and black Africans, preventing them from aiding Boer guerrillas. Tragically, over 27,000 Boers and 14,000 Africans, many of them children died in the camps from disease and starvation.

Another lesser-known atrocity occurred between 1904 and 1907 in Namibia, carried out by the forces of Kaiser Wilhelm II. The Herero and Nama (Namaqua) genocide, considered one of the first genocides of the 20th century, was a campaign of racial extermination and collective punishment conducted by the German Empire in German South West Africa (modern-day Namibia).

In January 1904, the Herero people, led by Samuel Maharero, and the Nama (or Namaqua), led by Captain Hendrik Witbooi, rebelled against German colonial rule. In response, German General Lothar von Trotha launched a brutal military campaign. In August of that year, the Herero were defeated at the Battle of Waterberg and driven into the Omaheke Desert, where most perished from dehydration.

The Nama Rebellion in October 1904 met a similarly horrific fate. Under German colonial rule, native populations were systematically exploited. Their lands were confiscated and redistributed to German settlers while they were forced into slave labor. Livestock, a vital resource for the Herero and Nama, was also seized.

General von Trotha made his genocidal intentions clear in a letter written before the Battle of Waterberg:

“I believe that the nation as such should be annihilated, or, if this was not possible by tactical measures, have to be expelled from the country… This will be possible if the water-holes from Grootfontein to Gobabis are occupied. The constant movement of our troops will enable us to find the small groups of this nation who have moved backward and destroy them gradually.”

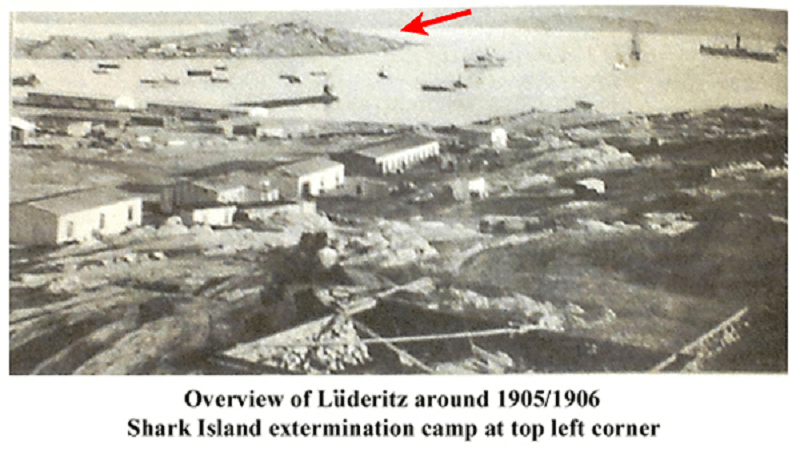

Despite von Trotha’s plans, his troops failed to annihilate the Herero absolutely. The survivors, mostly women and children, were captured and sent to concentration camps such as Shark Island, where they endured forced labor under horrific conditions.

In the camps, food was scarce, typically consisting of uncooked rice without any supplements. Lacking cooking utensils, the prisoners resorted to eating indigestible meals. Dead animals were later distributed as food, further degrading their health. Diseases such as dysentery and lung infections were rampant, and medical care was nonexistent. Meanwhile, forced labor continued under brutal treatment by German guards. Many were beaten, hanged, or shot, with survivors dying from starvation and exhaustion.

In 1905, a South African newspaper, Cape Argus, described the abuses in an article titled:

“In German S.W. Africa: Further Startling Allegations: Horrible Cruelty.”

The Herero and Nama were not savages, as German propaganda claimed. The Herero had a sophisticated culture and deep ties to their ancestral lands. The Nama, often of mixed Dutch descent, were not only skilled warriors but also Christians.

Approximately 3,500 innocent Africans were massacred in Namibia decades before the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. These atrocities were carried out with the tacit approval of Kaiser Wilhelm II and his administration.

Despite the gravity of these events, they have largely been erased from historical narratives. Even today, visitors to Shark Bay find little mention of this genocide.

Disturbingly, some scholars suggest that Nazi crimes during World War II were not an isolated aberration but part of a deeply entrenched tradition of racial superiority within German ideology. This belief system, rooted in the 19th century, justified such atrocities.

In 1908, Eugen Fischer, a German professor of medicine, anthropology, and eugenics, conducted field research in Namibia. He studied the Basters—mixed-race descendants of German or Boer men and native women—and advocated for prohibiting interracial marriage to preserve racial purity. Fischer’s unethical experiments on Herero and Nama prisoners laid the groundwork for his later work under the Nazi regime, influencing the Nuremberg Laws.

By 1912, Fischer’s recommendations had led to a ban on interracial marriages across German colonies. Fischer also collected skulls and bones from his victims, further dehumanizing the Herero and Nama and foreshadowing the horrors of Nazi Germany.

The Stages of Genocide

In 1987, Gregory Stanton, a law professor, published a paper outlining how genocides develop and unfold. In this seminal work, Stanton identified eight key stages that lead to acts of genocide. He noted that these stages may occur simultaneously or in a different order, depending on the context.

In 2012, Stanton expanded his model to include two additional stages—Discrimination and Persecution—bringing the total to ten. His updated framework provides a comprehensive guide to understanding the progression of genocide:

- Classification: Dividing people into “us” and “them.”

- Symbolisation: Associating groups with specific symbols to mark them as different.

- Discrimination: Excluding groups from civil society, such as by barring them from voting, public spaces, or services. For example, in Nazi Germany, Jews were prohibited from sitting on certain park benches.

- Dehumanisation: Stripping a group of their humanity by equating them with animals or diseases to demean and marginalise them.

- Organisation: Preparing for persecution by training armed forces or police units and equipping them with the means to target a group.

- Polarisation: Using propaganda to deepen societal divides and further isolate the targeted group.

- Preparation: Strategically planning mass murder and identifying victims.

- Persecution: Forcibly displacing groups, incarcerating them in ghettos or concentration camps, and seizing their property and belongings.

- Extermination: Carrying out mass killings.

- Denial: Refusing to acknowledge the crimes committed, often justifying them as necessary or not criminal.

Stanton’s model—designed to aid in the early identification of genocidal processes—enabled interventions to prevent such atrocities before they escalated.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Nama_genocide

https://www.britannica.com/topic/German-Herero-conflict-of-1904-1907#ref1102513

https://namibian.org/news/history/ovaherero-commemorate-the-extermination-order-of-lothar-von-trotha

Donations

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment