I have seen this image on several platforms identified as baby Gerhard Kretschmar and his mother, but I have been unable to verify its authenticity. Regardless, the story of Gerhard Kretschmar remains a harrowing reflection of history.

The shocking reality behind the inception of Aktion T4, or the T4 program, is that its first victim was not chosen by the Nazi regime but by the victim’s parents. I don’t want to judge the parents because I was never put in a similar position, and I don’t know what I would have done.

Gerhard Herbert Kretschmar (20 February 1939 – 25 July 1939) was a German infant born with severe disabilities. Following a petition from the child’s parents, Adolf Hitler personally authorized one of his physicians, Karl Brandt, to euthanize the child. This act marked the beginning of Nazi Germany’s so-called “euthanasia program,” Aktion T4, which would go on to claim the lives of approximately 200,000 people with mental and physical disabilities.

The T4 program, also known as Aktion T4, is the postwar name for the mass murder carried out through involuntary euthanasia in Nazi Germany. The name “T4” is derived from the address Tiergartenstraße 4 in Berlin, the location of the Chancellery department established in the spring of 1940 to recruit and oversee the personnel involved in the program.

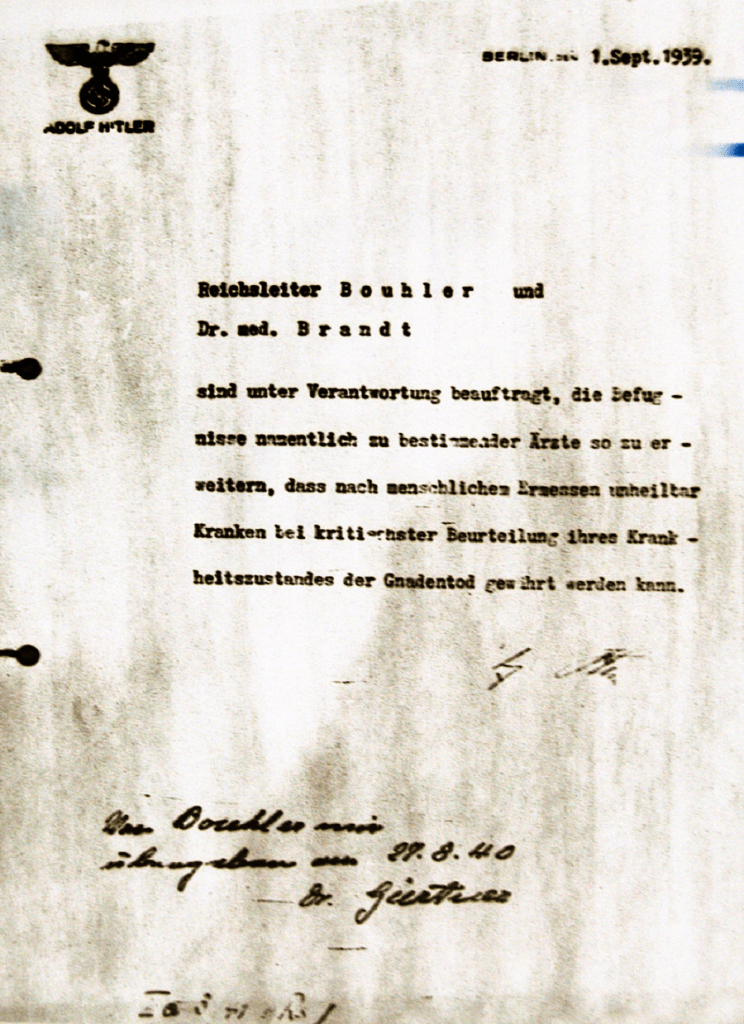

Under Aktion T4, certain German physicians were authorized to select patients “deemed incurably sick, after the most critical medical examination” and administer to them what was termed a “mercy death” (Gnadentod). Adolf Hitler signed a “euthanasia decree” in October 1939, backdated to 1 September 1939, which authorized his personal physician Karl Brandt and Reichsleiter Philipp Bouhler to implement the program.

The immediate catalyst for the organized euthanasia of children is often attributed in historical literature to the so-called case of “Child K.”

Beginning in October 1939, public health authorities actively encouraged parents of children with disabilities to admit their young ones to specially designated pediatric clinics across Germany and Austria. However, these clinics were, in reality, children’s killing wards. In these facilities, specially recruited medical staff murdered the children through lethal overdoses of medication or starvation.

In the case of “Child K,” the parents submitted a request for a “mercy killing” for their severely disabled child. The application was received at an unverifiable date before mid-1939 by the Office of the Führer (Kanzlei des Führers, or KdF), also known as Hitler’s Chancellery. This office, an agency of the Nazi Party directly under Hitler’s authority, employed around 195 staff members by 1939.

Responsibility for handling such “clemency” requests fell to Main Office IIb, led by Hans Hefelmann and his deputy, Richard von Hegener. Their superior, Oberdienstleiter Viktor Brack, was the head of Main Office II and one of the principal architects of the Nazi euthanasia program.

Reports about the case of “Child K” are primarily based on statements made by defendants during post-war trials, who repeatedly referenced this case. According to French journalist Philippe Aziz, the child was allegedly traced in 1973 to a family named Kressler in Pomßen. However, after extensive investigation, historian Udo Benzenhöfer concluded that “Child K” was actually Gerhard Herbert Kretschmar, born on February 20, 1939, in Pomßen, and who died on July 25, 1939.

Until recently, the identity of the child known as “Child K” had not been publicly disclosed, although it was known to German medical historians. Historian Udo Benzenhöfer argued that revealing the child’s identity was prohibited under Germany’s privacy laws concerning medical records.

In 2007, however, historian Ulf Schmidt published the child’s name, as well as the names of the parents, the place of birth, and the dates of birth and death, in his biography of Karl Brandt. Schmidt justified this decision by emphasizing the importance of recognizing the child’s individuality and suffering. He wrote:

“Although this approach [of Benzenhöfer and others] is understandable and sensitive to the feelings of the parents and relatives of the child, it somehow overlooks the child itself and its individual suffering… By calling the child ‘Child K,’ we would not only medicalize the child’s history but also place the justifiable claim of the parents for anonymity above the personality and suffering of the first ‘euthanasia’ victim.”

Schmidt did not disclose whether the child’s parents were still living at the time of publication.

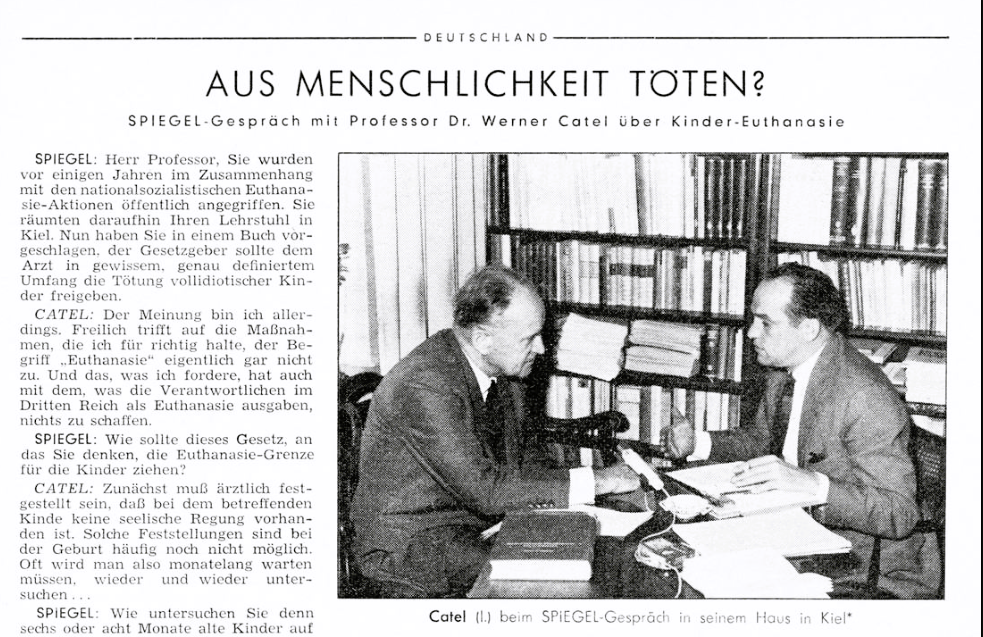

According to participant testimony, a request submitted on May 23, 1939, led to a meeting between the parents of the child and Werner Catel, the director of the University Children’s Hospital in Leipzig. The meeting focused on the chances of survival for their severely malformed child.

According to Catel’s own later statements, he believed that releasing the child through an early death was the most compassionate solution for everyone involved. However, as actively assisting in death was still punishable under the laws of the Third Reich, Catel advised the parents to submit a formal request to Hitler through his private chancellery.

Regarding this request, Hans Hefelmann, a key figure in the process, made the following statement before an investigating judge on November 14, 1960:

“I worked on this request, as it was in my department. Since Hitler’s decision was requested, I forwarded it without comment to the Head of Main Office I in the KdF, Albert Bormann. As a simple act of mercy was being requested, I did not deem the involvement of the Reich Interior Minister and the Minister of Justice necessary. Because, as far as I know, Hitler had not made a decision with regards to such requests, it also seemed impractical to me to involve other authorities.”

Richard von Hegener, deputy to Hans Hefelmann, provided additional context in his recollections:

*”As early as about half a year before the outbreak of the war, we began to receive an increasing number of requests from individuals who were incurably ill or gravely injured, pleading for relief from their unbearable suffering. These requests were particularly tragic because, under existing laws, doctors were prohibited from acting on such wishes.

Since our department was explicitly tasked, as we were repeatedly reminded, to address cases that could not be resolved legally, Dr. Hefelmann and I eventually felt compelled to bring a number of these requests to Hitler’s personal physician, the senior doctor Dr. Karl Brandt. We asked him to present these cases to Hitler and seek his decision on how to handle such requests.

Not long after, Dr. Brandt informed us that Hitler had decided, based on this presentation, to approve such requests. However, this approval was contingent on confirmation by the patient’s attending physician, along with verification from a newly formed health committee, that the suffering was indeed incurable.”

During the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial, Brandt said the following about the case of “Child K”:

“I personally know of a petition that was sent to the Führer in 1939 via his adjutant’s office [Adjutantur]. The case was about the father of a malformed child who applied to the Führer, asking that the life of this child or this creature would be taken. At the time, Hitler ordered me to address this matter and to go to Leipzig immediately – it had happened in Leipzig – in order to confirm on the spot what had been asserted. I found that there was a child who had been born blind, appeared imbecilic, and was also missing a leg and part of the arm. […] He [Hitler] had given me the task to discuss with the doctors in whose care the child was to determine whether the disclosure of the father was correct. In the event that he was right, I was to tell the doctors, in his [Hitler’s] name, that they could carry out euthanasia. In doing so, it was important that it should be done in such a way that the parents could not feel at any later stage that they themselves were burdened by the euthanasia [of their child]. In other words, these parents should not have the impression that they themselves were responsible for the death of the child. It was further beholden on me to say that if these doctors themselves were involved in any legal proceedings as a result of these measures carried out on behalf of Hitler, these proceedings would be quashed. Martin Bormann was then tasked, to notify this accordingly to the then Minister of Justice, Gürtner, in respect of this case in Leipzig. […] The doctors were of the opinion that preserving the life of such a child was not actually justified. It was pointed out that it is quite normal that in maternity hospitals under certain circumstances for euthanasia to be administered by the doctors themselves in such a case, without calling it such, any more precise term is not used.”

Sources

https://www.t4-denkmal.de/eng/Werner-Catel

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.uvic.ca/humanities/germanicslavic/assets/docs/jcura/sarah-wald-poster_sarah-wilkinson.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerhard_Kretschmar

Please donate so we can continue this important work

Donations

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment