Paragraph 175 was a provision of the German Criminal Code that criminalized male homosexual acts. Introduced in 1871 and remaining in some form until 1994, this law had a profound impact on the lives of LGBT individuals in Germany. It led to widespread persecution, particularly under the Nazi regime, and its effects persisted through much of the 20th century. The eventual repeal of Paragraph 175 marked a significant step in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights in Germany and beyond.

Origins and Early Enforcement

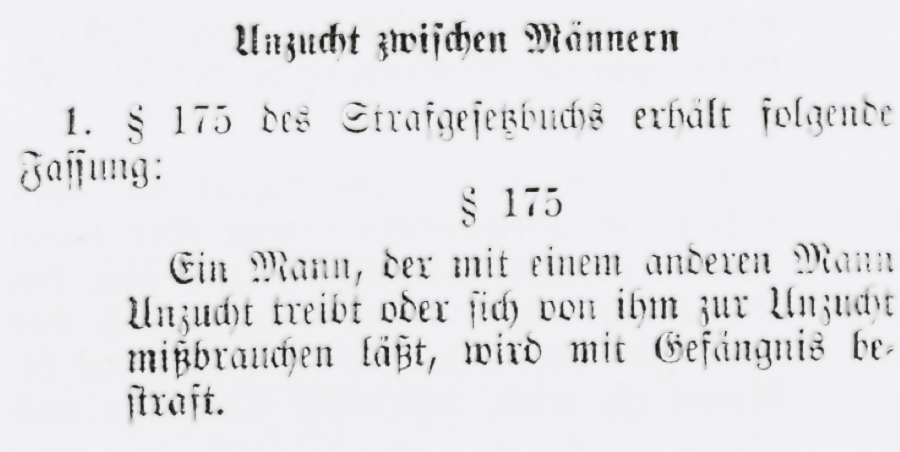

Paragraph 175 was first established in 1871 when Germany was unified under the German Empire. The law stated: “An unnatural fornication committed between persons of the male sex or by humans with animals is punishable by imprisonment.” While enforcement varied, convictions were relatively low in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The law primarily reflected conservative societal attitudes toward homosexuality rather than an active effort to root it out.

Persecution Under the Nazi Regime

The Nazi era (1933-1945) saw an aggressive expansion of anti-LGBT policies, with Paragraph 175 becoming a tool for persecution. In 1935, the law was revised to broaden the definition of “unnatural fornication” to include even non-physical expressions of homosexuality, such as suggestive gestures or letters. This led to a dramatic increase in arrests and convictions. It is estimated that between 5,000 and 15,000 men were sent to concentration camps for homosexuality, where they were subjected to horrific treatment, including forced castration, medical experiments, and executions.

In 1935, the Nazis expanded Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code, allowing courts to prosecute any “lewd act” between men, even those involving no physical contact, such as mutual masturbation.

As a result, convictions skyrocketed tenfold, exceeding 8,000 per year by 1937. Additionally, the Gestapo had the authority to send suspected offenders to concentration camps without legal justification—regardless of whether they had been acquitted or had already served their sentence. Consequently, over 10,000 homosexual men were deported to concentration camps, where they were marked with pink triangles. The majority perished there.

Between 1933 and 1945, according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), an estimated 100,000 men were arrested for violating this law, with approximately half serving prison sentences. It is believed that between 5,000 and 15,000 men were sent to concentration camps due to their sexuality. However, the exact number of fatalities remains unknown due to limited surviving documentation and the reluctance of many survivors to speak about their experiences.

When reforming Paragraph 175 in 1935, Nazi legislators had the opportunity to extend its provisions to women but chose not to. Nazi ideology emphasized the role of women in producing racially pure “Aryan” children, and they believed that lesbian women could be coerced into fulfilling their reproductive duties. Furthermore, as women generally did not hold positions of power in the military, economy, or politics, the Nazis did not consider female homosexuality a direct threat to the state.

After the annexation of Austria in 1938, Paragraph 175 was enforced there as well. One of its victims was Josef Kohout, whose story is recounted in Heinz Heger’s book The Men With the Pink Triangle: The True, Life-and-Death Story of Homosexuals in the Nazi Death Camps.

Excerpt from Josef Kohout’s Story:

Vienna, March 1939

I was twenty-two years old, a university student preparing for an academic career—an aspiration that pleased both my parents and myself. Politics did not interest me; I was not affiliated with the Nazi student association or any of the party’s other organizations.

I had no particular opposition to the new Germany—after all, German was my mother tongue. However, my upbringing was distinctly Austrian, and my parents had instilled in me a sense of tolerance. In our home, we made no distinctions based on language, religion, or skin color, and we respected differing opinions, no matter how unusual they seemed.

Thus, when Nazi ideology began to permeate the university, asserting the supremacy of the “German master race” and its destiny to rule Europe, I found it deeply arrogant. This alone made me wary of Austria’s new Nazi rulers and their beliefs.

I came from a well-to-do, strictly Catholic family. My father, a senior civil servant, was a model of discipline and integrity. He treated my mother with great respect, never forgetting her birthday or saint’s day. My mother, who is still alive today, was the very embodiment of kindness, always ready to support us. She was not just a mother but also a trusted friend to whom I could confide anything.

Since the age of sixteen, I had known that I was more attracted to men than to women. Initially, I thought little of it, but as my schoolmates began dating girls while I remained drawn to another boy, I was forced to confront what this meant. I enjoyed the company of girls, but I saw them as friends and equals rather than romantic interests. Although I attempted relationships with women, they felt unnatural to me.

For three years, I kept my feelings hidden, even from my mother. Eventually, the secrecy became unbearable, and I confided in her—not seeking advice, but simply to ease my burden. She responded with warmth and wisdom:

“My dear child, this is your life, and you must live it. No one can change who they are. If you find happiness with another man, that does not make you any less of a person. Just be cautious, avoid bad company, and protect yourself from blackmail. Try to find a lasting relationship—it will shield you from many dangers. I have suspected this for some time. Whatever happens, you are my son, and you can always come to me.”

Her words reassured me deeply. At university, I met other students who shared my feelings, forming a small but supportive group. After the Nazi annexation, our circle grew as students from the Reich joined us. In late 1938, I met the love of my life—Fred, the son of a high-ranking Nazi official. He was strong yet sensitive, excelling in sports and academics. We fell deeply in love and envisioned a future together.

One afternoon in March 1939, our world shattered. A man in a leather coat rang our doorbell and presented a summons: “Gestapo.” I was ordered to report for questioning at 2 p.m. at their headquarters in the Hotel Metropol.

My mother and I were terrified, but I reassured her: “It can’t be serious, or they would have taken me away immediately.”

Through the window, I saw the agent loitering nearby, clearly keeping watch. When I bid my mother farewell, she embraced me tightly and whispered, “Be careful, child, be careful!” Neither of us imagined that we would not see each other again for six years—her a broken woman, me a shattered man.

My father, subjected to relentless social stigma, was forced into early retirement in December 1940. In 1942, overwhelmed by despair and humiliation, he took his own life. In his farewell letter to my mother, he wrote: “I can no longer endure the scorn of my colleagues and neighbors. It is too much for me. Please forgive me. God protect our son.”

Imprisonment and Survival

I was taken to Vienna’s Rossauerlände prison, where I was denied contact with my mother. “She will soon know you’re not coming home,” they told me coldly.

After a humiliating body search, I was placed in a cell with two common criminals. When they learned I was homosexual, they first propositioned me and then, upon my refusal, subjected me to relentless verbal abuse. To them, I was “subhuman,” an animal who deserved extermination. Yet, despite their contempt, they engaged in sexual acts with each other, dismissing it as a mere “emergency outlet”—a hypocrisy I would encounter repeatedly.

Within weeks, I was swiftly sentenced under Paragraph 175 to six months of penal servitude, with one fasting day per month. My beloved Fred was spared—his influential Nazi father had intervened. On the day of my scheduled release, I was informed that the Central Security Department had ordered my continued detention. I was to be sent to a concentration camp.

I had heard the fate that awaited men like me in the camps—tortured, worked to death, rarely surviving. But at that moment, I refused to believe it.

The Camps and Aftermath

In January 1940, I was deported to Sachsenhausen, later transferred to Flossenbürg. Unusually for a homosexual prisoner, I was assigned as a Kapo, overseeing forced labor at the train station. I survived, I believe, due to my connections with “green” (criminal) Kapos. During a death march in April 1945, I escaped near Cham.

Josef Kohout lived in Vienna with his partner until his death on March 15, 1994—three months before Paragraph 175 was finally abolished.

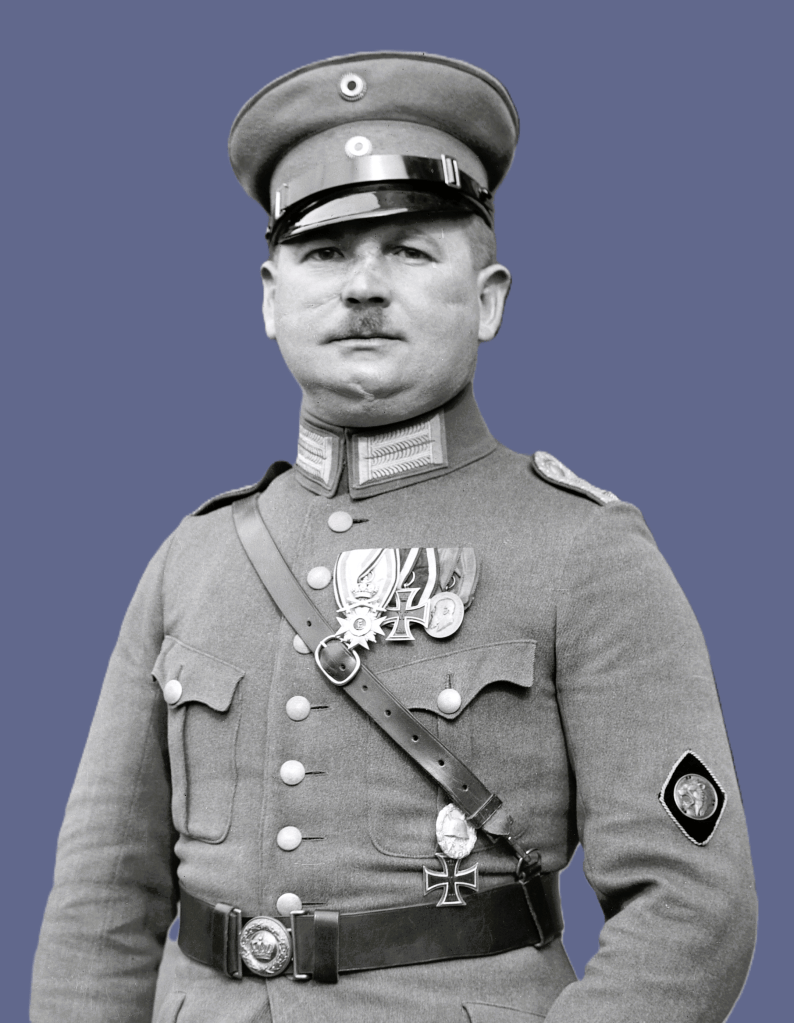

Ernst Röhm

Ernst Röhm was a German military officer and a key figure in the early Nazi Party, serving as the leader of the Sturmabteilung (SA), the Nazi paramilitary wing. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, Röhm played a crucial role in the party’s rise to power. However, his growing influence and push for a “second revolution” to empower the SA led to tensions with Hitler and other Nazi leaders. In 1934, during the Night of the Long Knives, Hitler ordered Röhm’s execution to consolidate power and appease the German military.

Röhm was openly homosexual, an unusual fact for a high-ranking Nazi official. He never hid his sexuality, and it was well known within Nazi circles. Despite the Nazi regime’s persecution of LGBT individuals, Hitler tolerated Röhm’s homosexuality for years due to their close friendship and Röhm’s political usefulness. However, after Röhm’s fall from favor, the Nazis used his sexuality as part of their justification for his execution, framing him as morally corrupt and a liability to the regime.

Initially, Hitler shielded Ernst Röhm from factions within the Nazi Party that viewed his homosexuality as a violation of its strict anti-gay policies. However, as Röhm’s influence grew, Hitler came to see him as a potential threat to his power. During the Night of the Long Knives in 1934—a purge targeting individuals Hitler perceived as rivals—Röhm was executed. To quell dissent within the SA, Hitler framed Röhm’s homosexuality as a justification for his elimination

Post-War Persistence

Despite the fall of the Nazi regime, Paragraph 175 remained in effect in both East and West Germany. In West Germany, the stricter Nazi-era version of the law continued to be enforced until 1969, leading to the arrest and imprisonment of thousands of men. The stigma attached to those convicted under Paragraph 175 persisted, affecting their employment and social standing. In East Germany, enforcement was less severe, and the law was gradually relaxed before being abolished in 1968.

Gradual Repeal and Recognition of Injustice

West Germany began to reform Paragraph 175 in 1969, decriminalizing consensual homosexual acts between adults over 21. In 1973, the age of consent was lowered to 18, and in 1994, following German reunification, Paragraph 175 was completely repealed. The German government later acknowledged the injustices suffered by those convicted under the law. In 2002, the convictions of men persecuted under Nazi rule were annulled, and in 2017, Germany formally pardoned and compensated men convicted under Paragraph 175 after World War II.

Legacy and Lessons

The history of Paragraph 175 serves as a stark reminder of the dangers of state-sanctioned discrimination. It underscores the resilience of the LGBT community in the face of systemic oppression and the importance of legal and social reforms in advancing human rights. Today, Germany stands as a leader in LGBT rights, offering legal protections, marriage equality, and anti-discrimination laws. The repeal of Paragraph 175 and subsequent reparations reflect a broader commitment to justice and equality.

In conclusion, Paragraph 175 was one of the longest-lasting anti-LGBT laws in modern history, reflecting the deep-seated prejudices that have historically existed in many societies. Its eventual repeal was a crucial victory for human rights, demonstrating the power of activism, legal reform, and societal change in addressing past injustices. The history of Paragraph 175 continues to serve as an important lesson on the need for vigilance against discrimination and the ongoing fight for equality.

sources

https://www.gedenkstaette-flossenbuerg.de/en/history/prisoners/josef-kohout

https://time.com/5295476/gay-pride-pink-triangle-history/

https://jewishcurrents.org/the-men-with-the-pink-triangle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernst_R%C3%B6hm#

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/roehm-purge

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment