On the night of August 7, 1930, the small city of Marion, Indiana became the site of one of the most infamous and haunting episodes of racial violence in American history—the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith.

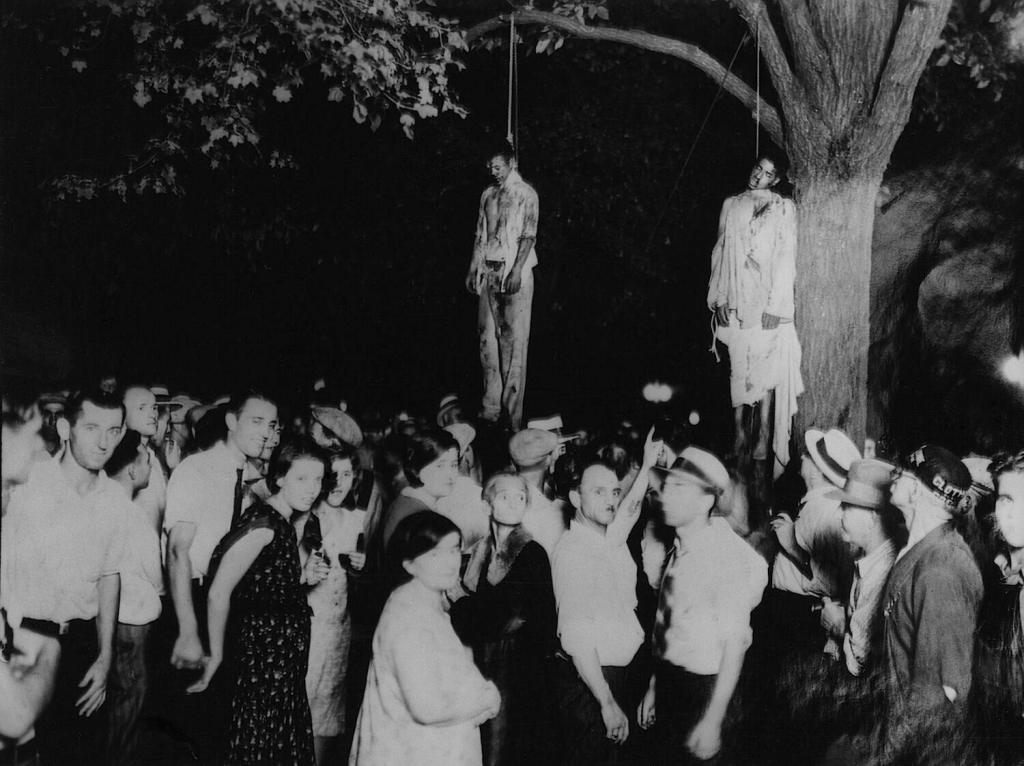

What makes this event particularly searing in the American consciousness isn’t just the brutality of the act. It’s the photograph. Captured by Lawrence Beitler, the image of Shipp and Smith’s bodies hanging from a tree—surrounded by a crowd of white spectators, some smiling, others pointing—has become one of the most iconic and horrifying visual records of the Jim Crow era. It is both a piece of evidence and a mirror: reflecting not just a moment of mob violence, but a system of white supremacy deeply rooted in American society.

The Accusation

Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith were both African American teenagers—18 and 19 years old. On August 6, 1930, they were arrested, along with 16-year-old James Cameron, for allegedly robbing and murdering Claude Deeter, a white man, and raping his white girlfriend, Mary Ball. The truth of these allegations was never proven in court, and Mary Ball later recanted the rape accusation. But none of that mattered to the mob that gathered the following night outside the Grant County Jail.

Fueled by rage and racism, a crowd of thousands—men, women, and children—descended upon the jail. They battered down the doors and dragged Shipp and Smith into the town square. There was no trial, no legal process. The law, in this moment, was irrelevant. They were beaten, mutilated, and hanged from a sycamore tree. Smith reportedly tried to fight back even with a broken arm, and according to some accounts, was stabbed before he died. Shipp died first.

James Cameron was next. The mob seized him, placed a noose around his neck, and prepared to hang him. But something remarkable happened: someone in the crowd shouted that he was innocent. For reasons still not fully understood—perhaps uncertainty, perhaps divine intervention—the crowd let him go. Cameron would later become a civil rights activist and found America’s Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee.

The Photograph

Beitler developed and sold thousands of copies of the photograph within days. It shows Shipp and Smith’s lifeless bodies hanging, their faces swollen and dark. Below them are white spectators—some children, some men in straw hats, some women in dresses. No one in the photo looks ashamed.

The image was widely circulated and even sold as postcards. It later inspired the poem “Strange Fruit” by Abel Meeropol, which Billie Holiday transformed into a haunting protest song that gave a sound to the silent horror of lynching in America.

No Justice Served

No one was ever held accountable for the lynchings of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith. Despite the large crowd and clear photographic evidence, no indictments were made. The silence of the justice system was deafening, and all too familiar.

The failure to prosecute any member of the lynch mob was not unusual in the Jim Crow era. Between 1882 and 1968, more than 4,700 lynchings were recorded in the United States—most of the victims Black men. In nearly all cases, justice was never served.

Legacy and Memory

James Cameron’s survival was a rare mercy, but it came with the burden of memory. He spoke about the lynching for the rest of his life, refusing to let the world forget. His museum, opened in 1988, stands as one of the few institutions solely dedicated to the history of racial violence in America.

Today, the site of the lynching in Marion is marked by a memorial. In 2022, a historical marker was erected to acknowledge the atrocity, offering a long-overdue act of public memory.

Why It Still Matters

To confront the legacy of lynching is to confront the foundations of systemic racism in America. The lynching of Shipp and Smith was not just an act of mob violence—it was a tool of terror, designed to reinforce white supremacy and suppress Black agency.

That photograph still shocks today not because it shows something unimaginable, but because it shows something all too real: that ordinary people can become complicit in extraordinary evil. The photo, the silence of the justice system, and the joyful faces in the crowd demand not just remembrance, but reckoning.

We live in a country still shaped by the legacy of such violence. The struggle for racial justice is not merely about history—it is about the present. To understand the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith is to understand the unfinished work of American democracy.

“This is a crime not only against two boys, not only against Negroes, but against America itself.”

– James Cameron, survivor of the lynching, 1993

Sources & Further Reading:

Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America by James Allen

A Time of Terror: A Survivor’s Story by James Cameron

Equal Justice Initiative: lynchinginamerica.eji.org

The Black Holocaust Museum: abhmuseum.org

sources

https://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/aug/7

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lynching_of_Thomas_Shipp_and_Abram_Smith

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment