It is Sunday evening—you turn on the radio and the news breaks that planet Earth is invaded by Mars. So what do you do? You panic, of course.

Well, that was the case for many when they switched on the radio on 30 October 1938.

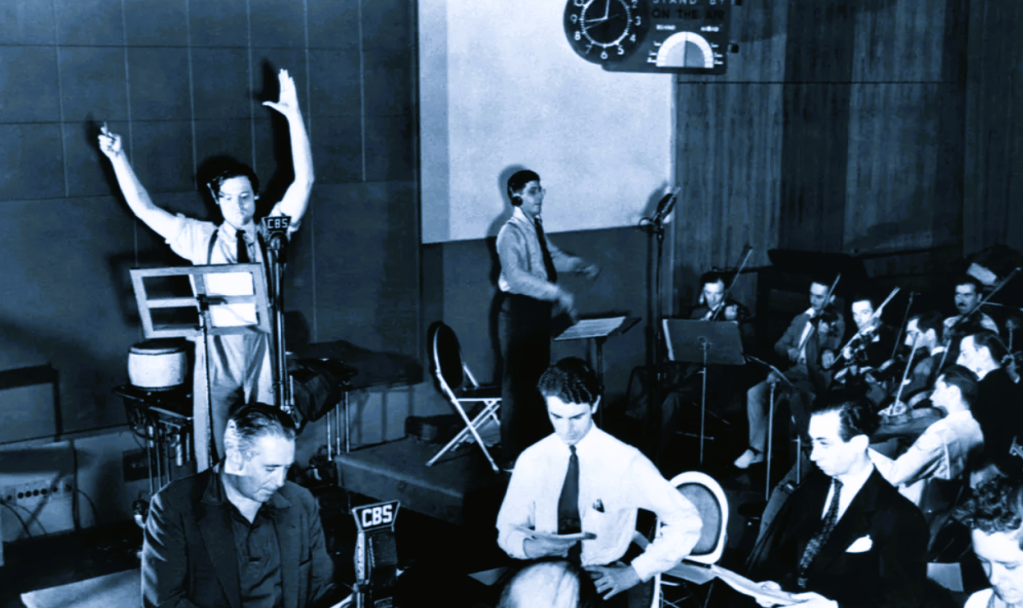

By the end of October 1938, Welles’s Mercury Theatre on the Air had been on CBS for 17 weeks. A low-budget program without a sponsor, the series had built a small but loyal following with fresh adaptations of literary classics. But for the week of Halloween, Welles wanted something very different from the Mercury’s earlier offerings. The show began on Sunday, 30 October, at 8 pm ET. A voice announced, “The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations present Orson Welles and the Mercury Theater on the air in War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells.”

Network radio on Sunday nights in the fall of 1938 was dominated by a ventriloquist. Edgar Bergen and his wooden dummy Charlie McCarthy, plus a host of visiting guests, tickled NBC listeners at 8:00 pm week after week. No program, it seemed, could compete with the Bergen/McCarthy appeal. Failing to dent the NBC ratings blockbuster, CBS gave their competing hour over to “The Mercury Theater on the Air,” a low-budget series that presented a different drama each week to the few non-Bergen fans who might listen. Many tuned in late after listening to Bergen and McCarthy’s opening scene. And therein lay one of the secrets of the Orson Welles drama’s impact.

Another factor was timing. Only the month before, listeners stayed close to their radios for days as Europe appeared to be heading into war during the Munich Crisis of September. They came to expect radio journalists to break into programming with the latest events.

Listeners had grown to fully trust what they could hear. Welles played on this as he and his cast pretended to be something quite different than they initially seemed.

Welles introduced his radio play with a spoken introduction, followed by an announcer reading a weather report. Then, seemingly abandoning the storyline, the announcer took listeners to “the Meridian Room in the Hotel Park Plaza in downtown New York, where you will be entertained by the music of Ramon Raquello and his orchestra.” Putrid dance music played for some time, and then the scare began. A radio announcer broke into the broadcast, saying that “Professor Farrell of the Mount Jenning Observatory had detected explosions on the planet—Mars.” Then the dance music came back on, followed by another interruption in which listeners were informed that a large meteor had crashed into a farmer’s field in Grovers Mills, New Jersey.

Soon, an announcer was at the crash site describing a Martian emerging from a large metallic cylinder. “Good heavens,” he declared, “something’s wriggling out of the shadow like a gray snake. Now here’s another and another one and another one. They look like tentacles to me … I can see the thing’s body now. It’s large, large as a bear. It glistens like wet leather. But that face, it… it … ladies and gentlemen, it’s indescribable. I can hardly force myself to keep looking at it, it’s so awful. The eyes are black and gleam like a serpent. The mouth is kind of V-shaped with saliva dripping from its rimless lips that seem to quiver and pulsate.”

The Martians mounted walking war machines and fired “heat-ray” weapons at the puny humans gathered around the crash site, and then annihilated a force of 7,000 National Guardsmen. After being attacked by artillery and bombs, the Martians released a poisonous gas into the air. Soon, “Martian cylinders” landed in Chicago and St. Louis. The radio play was extremely realistic, with Welles employing sophisticated sound effects and his actors—doing an excellent job—portraying terrified announcers and other characters. An announcer reported that widespread panic had broken out in the vicinity of the landing sites, with thousands desperately trying to flee.

The Federal Communications Commission investigated the unorthodox program but found no law was broken. Networks did agree to be more cautious in their programming in the future. The broadcast helped Orson Welles land a contract with a Hollywood studio. In 1941, he directed, wrote, produced, and starred in Citizen Kane—a movie that many refer to as the best American film ever made.

Sources

Leave a comment