The Pacific War (1941–1945) reshaped Southeast Asia and subjected millions to brutal occupation under Imperial Japan. Among the most harrowing stories is that of Batu Lintang camp, located on the outskirts of Kuching in Sarawak, Borneo. Originally a British military barracks, the Japanese converted it into an internment and prisoner-of-war (POW) camp after their conquest of Borneo in early 1942. For more than three years, it housed European civilians and Allied POWs, who endured malnutrition, disease, and fear of execution. Its liberation by Australian forces in September 1945 revealed both the resilience of its inmates and the imminent threat of mass murder that had hung over them. The liberation of Batu Lintang is thus both a dramatic rescue story and a stark reminder of the war’s human cost.

Japanese Occupation of Borneo and the Creation of Batu Lintang Camp

The Japanese invaded Borneo in December 1941, shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor. British, Dutch, and Australian forces stationed on the island were quickly overwhelmed. By January 1942, Kuching had fallen, and the Japanese consolidated control over Sarawak. They transformed the Batu Lintang military barracks into a camp designed to hold different categories of detainees: British and Dutch military personnel, civilian administrators, missionaries, teachers, and their families, including women and children.

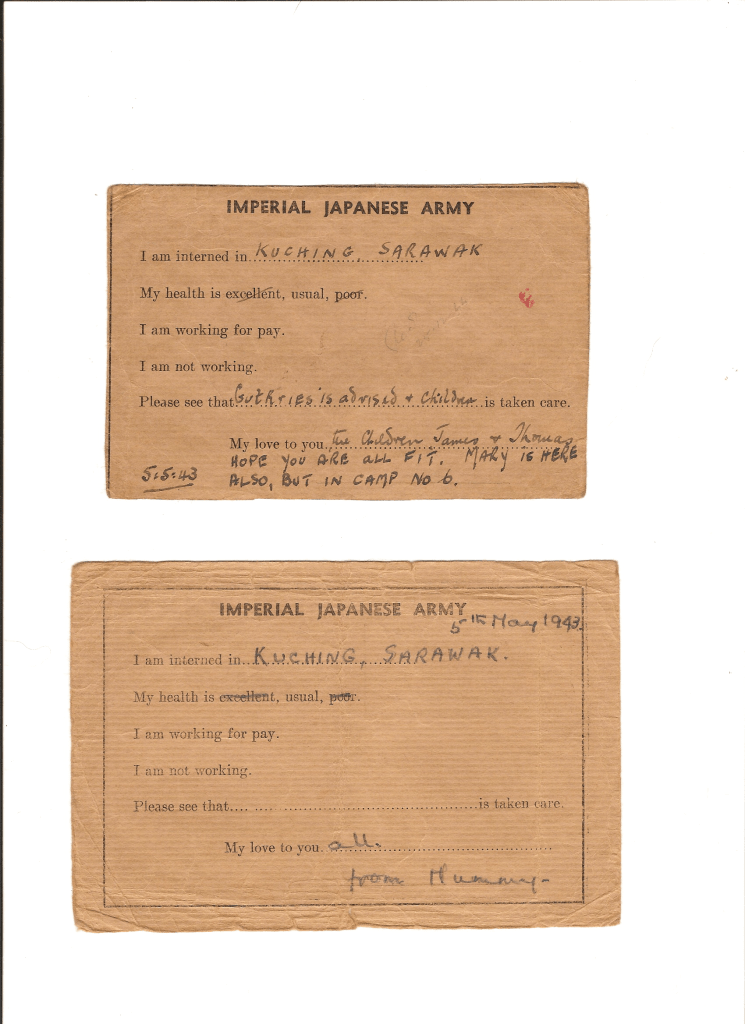

The Japanese administered the camp through military police (Kempeitai), notorious for their harsh discipline and brutality. Prisoners were separated into compounds according to gender and status, with POWs in one area and civilians in another. Overcrowding, limited food supplies, and forced labor created conditions of extreme hardship. Yet despite restrictions, internees found ways to maintain morale: clandestine schools and libraries operated, chaplains organized religious services, and hidden radios provided news from the outside world.

Daily Life: Survival Amidst Hardship

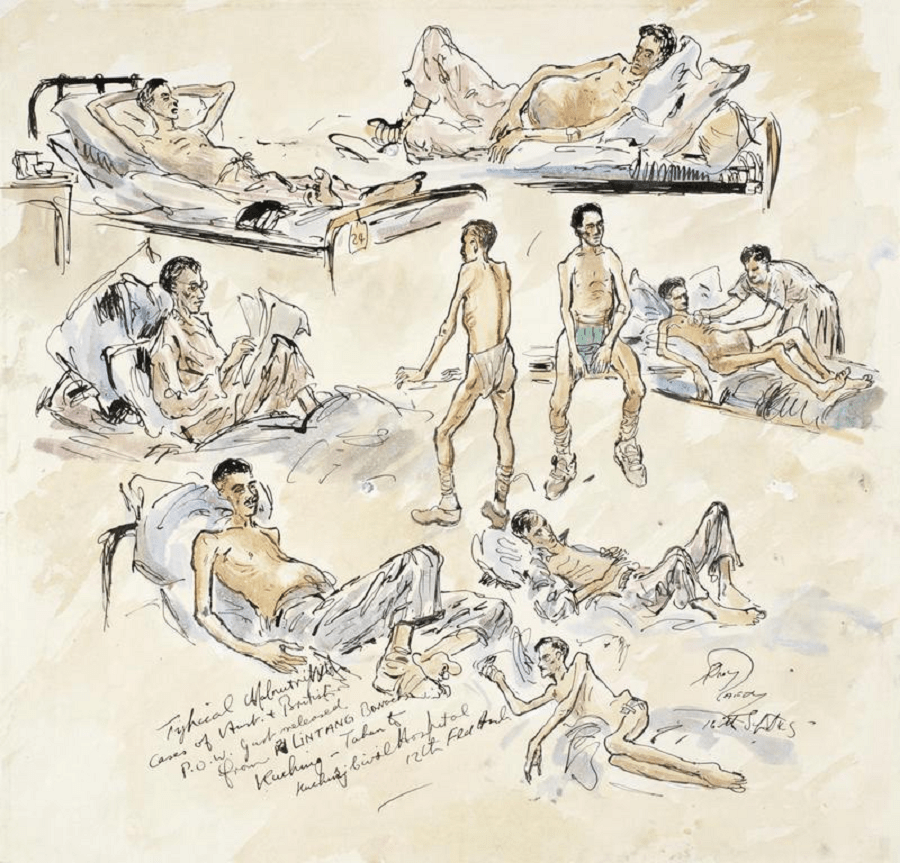

Food shortages defined existence at Batu Lintang. Rations often consisted of small portions of rice supplemented by watery vegetable soup. Protein was scarce, and many prisoners resorted to catching insects or cultivating secret gardens to supplement their diets. Malnutrition led to widespread beriberi, pellagra, malaria, and dysentery, conditions worsened by the lack of medical supplies.

Testimonies from survivors emphasize the psychological as well as physical toll. Prisoners lived under constant surveillance, with beatings and punishments common for infractions such as hoarding food or attempting to communicate across fences. Women struggled to care for children under conditions of starvation, while POWs were often forced to work on infrastructure projects. Despite this, acts of resistance and solidarity persisted. One famous example was the clandestine newspaper and radio operation, which disseminated news of Allied advances, bolstering morale and providing hope of eventual liberation.

The Threat of Massacre

By mid-1945, with the Japanese war effort collapsing, conditions in the camp deteriorated further. The fear of massacre loomed large, as Japanese forces elsewhere in Asia had executed prisoners to prevent their liberation by advancing Allies. In Batu Lintang, this fear was tragically justified: Allied troops later discovered a written order scheduling the execution of all prisoners on 15 September 1945. The order had been signed and only awaited implementation. Thus, the liberation of the camp was not only timely but life-saving.

The Borneo Campaign and Liberation

In 1945, the Allies launched the Borneo Campaign, with Australian forces playing a leading role under General Douglas MacArthur’s overall command. The campaign sought to recapture resource-rich territories and liberate civilian populations from Japanese occupation. After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, Japan announced its surrender, but Allied troops continued with planned landings to secure areas and disarm Japanese forces.

On 11 September 1945, a contingent of the Australian 9th Division, led by Brigadier Thomas Eastick, arrived in Kuching to accept the formal surrender of Japanese forces in Sarawak. When they entered Batu Lintang, they were met by emaciated but jubilant prisoners. Accounts describe a mixture of relief, disbelief, and overwhelming emotion. Many internees were near death from starvation and disease, but their survival had been secured just days before the planned executions. Liberation was not only a symbolic end to years of suffering but a literal rescue from imminent annihilation.

Aftermath and War Crimes Trials

Following liberation, survivors required urgent medical attention. Many were evacuated to Australia, Britain, or the Netherlands for treatment and recovery. Yet the trauma endured by survivors—physical debilitation, psychological scars, and loss of loved ones—remained for years.

The discovery of the execution orders, coupled with testimonies of mistreatment, formed part of the evidence in post-war war crimes trials conducted by Allied military tribunals. Several Japanese officers and guards associated with Batu Lintang were tried for their roles in mistreatment and deaths of prisoners. While some were executed or imprisoned, others escaped justice due to lack of evidence or the complexities of post-war politics.

Memory and Legacy

Batu Lintang camp was later converted into an educational institution, and parts of the site remain preserved as a memorial. Survivors and their descendants have worked to keep the memory alive through memoirs, oral histories, and commemorations. The camp symbolizes both the cruelty of war and the resilience of the human spirit in adversity.

The liberation of Batu Lintang continues to resonate because it illustrates the precariousness of survival under Japanese occupation. It also highlights the role of Australian forces in liberating Borneo, a contribution sometimes overshadowed by larger campaigns in the Pacific. Most importantly, it stands as a warning against the dehumanization of war and the necessity of remembrance.

The liberation of Batu Lintang camp in September 1945 represents a crucial moment in the history of the Pacific War. More than a simple military victory, it was a race against time that saved hundreds of civilian internees and POWs from certain death. The camp’s story reveals the harsh realities of life under Japanese occupation, the resilience of prisoners in maintaining dignity amid deprivation, and the urgent necessity of justice in the post-war era. Today, Batu Lintang endures not only as a memorial site but as a testament to endurance, liberation, and the enduring human need to remember.

sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Batu_Lintang_camp

https://www.cofepow.org.uk/news/batu-lintang-pow-campsite-celebrates-75-years-of-liberation

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1500078109

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment