(Originally posted on March 10, 2016)

These days, it has become all too easy to blame Muslims for many of the world’s problems. I can understand why some people might feel that way, given the terrible acts of terrorism committed in the name of Islam in recent years — and which, sadly, continue to this day.

But the truth is that those who carry out such crimes twist Islam to serve their own distorted political agendas. Their actions have little to do with the faith itself. In fact, the greatest number of victims of this violence are Muslims.

So, before claiming that Muslims are a threat to Western freedom, remember people like Noor Inayat Khan — a Muslim woman who gave her life defending that very freedom.

Noor Inayat Khan was a wartime British secret agent of Indian descent and the first female radio operator sent into Nazi-occupied France by the Special Operations Executive (SOE). She was eventually captured and executed by the Gestapo.

Born on New Year’s Day, 1914, in Moscow to an Indian father and an American mother, Khan was a direct descendant of Tipu Sultan, the 18th-century Muslim ruler of Mysore. Her father, a musician and Sufi teacher, moved the family first to London and later to Paris, where Noor was educated and began her career writing children’s stories.

After the fall of France, Khan escaped to England and, in November 1940, joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). Two years later, in late 1942, she was recruited by the SOE as a radio operator. Although some of her trainers doubted her suitability for fieldwork, her fluent French, technical skill, and the urgent need for qualified agents made her a valuable candidate for service in Nazi-occupied France.

On the night of 16–17 June 1943, operating under the codename “Madeleine” and wireless call sign “Nurse”, Khan flew to northern France on a clandestine Lysander mission, landing at the site known as B/20A “Indigestion”. Using the cover identity Jeanne-Marie Regnier, she began her work transmitting vital messages to London. She was met by Henri Déricourt, who, tragically, turned out to be a double agent.

She travelled to Paris, and with two other women, Diana Rowden (code named Paulette/Chaplain), and Cecily Lefort (code named Alice/Teacher), joined the Physician network led by Francis Suttill (code named Prosper).

Over the following six weeks, the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) arrested all other radio operators in the Physician network, along with hundreds of Resistance members linked to the Prosper circuit. Despite the immense danger, Noor Inayat Khan refused an offer to return to Britain—a decision later noted by Colonel Maurice Buckmaster, head of the SOE’s F Section. Although it was in SOE’s interest for her to remain active after the collapse of its largest network, her choice also reflected her deep sense of duty.

As the only remaining wireless operator still at large in Paris, Khan continued transmitting messages to London on behalf of agents from what was left of the Prosper/Physician circuit. She worked tirelessly to maintain what remained of the network, despite the mass arrests of its members. Her courage and persistence made her the most wanted British agent in Paris. The SD circulated her description widely among German security officers, even dispatching teams to search for her in subway stations.

With wireless detection vans constantly tracking her signal, Khan never stayed in one place for more than twenty minutes at a time. She moved constantly from location to location, skillfully evading capture while keeping vital lines of communication open with London. One SOE report later noted:

“She refused to abandon what had become the most important and dangerous post in France and did excellent work.”

Eventually, Khan was betrayed to the Germans, possibly by Henri Déricourt or Renée Garry. Déricourt (code name Gilbert)—an SOE officer and former French Air Force pilot—had long been suspected of serving as a double agent for the Sicherheitsdienst. Garry, the sister of Henri Garry, Khan’s organizer in the Cinema (later Phono) network, was allegedly paid 100,000 francs for the betrayal. Some accounts suggest jealousy may have motivated her, as she believed SOE agent France Antelme had transferred his affections from her to Khan.

On or around 13 October 1943, Noor Inayat Khan was arrested and taken for interrogation at SD Headquarters, located at 84 Avenue Foch, Paris.

Although some of her SOE trainers had doubted her suitability for fieldwork, describing her as gentle and unworldly, Noor Inayat Khan displayed extraordinary courage upon her arrest. She fought so fiercely that the SD officers were reportedly afraid of her, and from that moment she was treated as an extremely dangerous prisoner.

There is no direct evidence that she was tortured, but her interrogation lasted for more than a month, during which she attempted to escape twice. According to Hans Kieffer, the former head of the SD in Paris who later testified after the war, Khan refused to reveal any information to the Gestapo, choosing instead to lie consistently to protect her colleagues and networks.

However, some other accounts suggest that she spoke amicably with one of her interrogators—an Alsatian officer dressed in civilian clothes—and may have revealed minor personal details about her childhood and family. These fragments of information reportedly helped the SD verify her identity during random checks, but there is no evidence that she compromised any operational secrets.

AAlthough Noor Inayat Khan refused to divulge her activities under interrogation, the SD discovered her notebooks. In them, she had copied all the messages she had sent as an SOE operative—a clear violation of security regulations. This may have been due to a misunderstanding of her orders regarding filing, as well as the truncated nature of her SOE training, which had been shortened to allow her early deployment to France.

While she never revealed any secret codes, the Germans were able to use the information in her notebooks to continue sending false messages in her name. London failed to properly detect anomalies in these transmissions—most notably changes in the operator’s “fist” (the distinctive style of Morse code), although historian M. R. D. Foot notes that the SD were skilled at mimicking operators’ fists.

As a WAAF signaller, Khan had been nicknamed “Bang Away Lulu” because of her heavy-handed Morse style, which was said to result from chilblains on her fingers.

Due to London’s errors in interpreting these messages, three additional SOE agents sent to France were captured upon landing, including Madeleine Damerment, who was later executed.

Sonya Olschanezky (“Tania”), a locally recruited SOE agent, learned of Khan’s arrest and sent a warning to London via her fiancé, Jacques Weil, advising that transmissions from “Madeleine” might be under enemy control. However, Colonel Maurice Buckmaster dismissed the message as unreliable, not realizing who Olschanezky was. Consequently, the Germans’ false transmissions continued to be treated as genuine, leading to the unnecessary deaths of multiple SOE agents, including Olschanezky herself, who was executed at Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp on 6 July 1944.

When Vera Atkins investigated the deaths of missing SOE agents, she initially confused Noor Inayat Khan with Sonya Olschanezky, due to their similar appearance. Unaware of Olschanezky, Atkins believed that Khan had been killed at Natzweiler, only correcting the record after discovering her true fate at Dachau.

On 25 November 1943, Inayat Khan escaped from the SD Headquarters in Paris, along with fellow SOE agents John Renshaw Starr and Leon Faye. An air raid alert occurred as they crossed the roof, and regulations required a count of prisoners during such alerts. Their escape was therefore discovered before they could get away.

After refusing to sign a declaration renouncing future escape attempts, Khan was transported to Germany on 27 November 1943 “for safe custody” and imprisoned at Pforzheim in solitary confinement. She was held under the “Nacht und Nebel” (“Night and Fog”) decree, condemned to disappear without a trace, and kept in complete secrecy. For ten months, she remained shackled at hands and feet, enduring harsh and isolating conditions.

Noor Inayat Khan was classified as “highly dangerous” and kept shackled in chains for most of her imprisonment. According to testimony from the prison director after the war, she remained uncooperative, refusing to divulge any information about her work or fellow operatives. Despite her stoicism, other prisoners could hear her crying at night, a testament to the despair caused by her appalling confinement. Yet, through the ingenious method of scratching messages on the base of her mess cup, she was able to inform another inmate of her true identity, giving the alias Nora Baker and her mother’s London address.

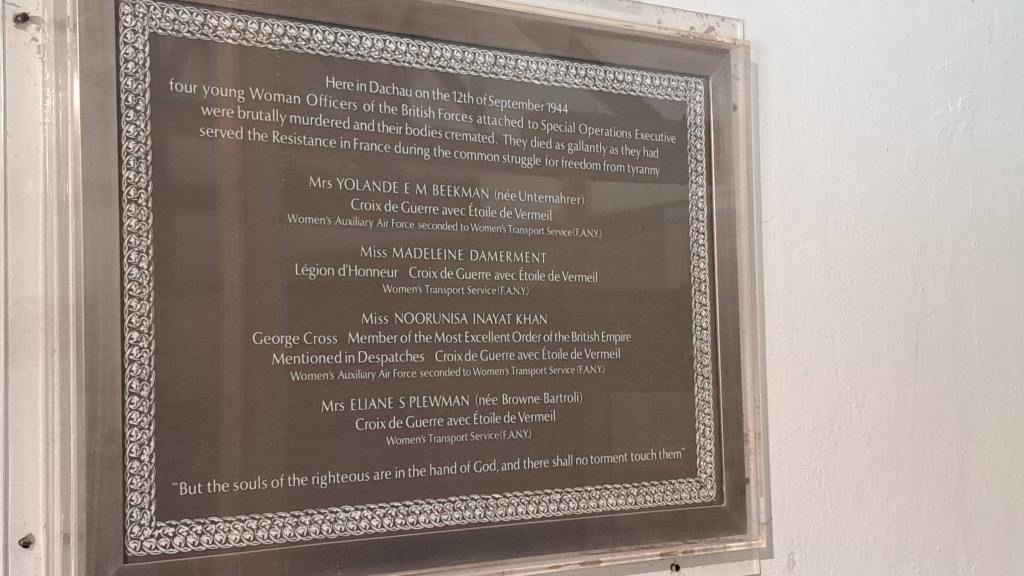

On 11 September 1944, Khan and three other SOE agents from Karlsruhe Prison—Yolande Beekman, Eliane Plewman, and Madeleine Damerment—were transferred to Dachau Concentration Camp. In the early morning hours of 13 September 1944, the four women were executed by a shot to the back of the head, and their bodies were immediately cremated.

An anonymous Dutch prisoner, speaking in 1958, reported that Khan was brutally beaten by a high-ranking SS officer, Wilhelm Ruppert, before being shot; the beating may have contributed to her death. She may also have been sexually assaulted while in custody. Her final recorded word was “Liberté”.

Noor Inayat Khan was posthumously awarded the George Cross in 1949, as well as the French Croix de Guerre with silver star.

Since she was still officially considered “missing” in 1946, she could not be recommended for appointment as a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE). Instead, she was Mentioned in Despatches in October 1946.

Inayat Khan was the third of three Second World War members of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) to receive the George Cross, Britain’s highest award for gallantry not in the face of the enemy.

At the beginning of 2011, a campaign was launched to raise £100,000 for a bronze bust of Noor Inayat Khan in central London, near her former home. It was claimed that this would be the first memorial in Britain to honor either a Muslim or an Asian woman. However, Inayat Khan had already been commemorated on the FANY memorial at St Paul’s Church, Wilton Place, Knightsbridge, London, which lists the 52 members of the Corps who gave their lives on active service.

The unveiling of the bronze bust by HRH The Princess Royal took place on 8 November 2012 in Gordon Square Gardens, London.

She is also commemorated on a stamp issued by the Royal Mail on 25 March 2014 in a set of stamps about “Remarkable Lives”

Although Noor Inayat Khan has been widely remembered and honored, it seems that her story is still not as well known as it deserves to be.

In 2014, a television movie titled The Enemy of the Reich was produced to commemorate her life and heroism.

sources

https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/inayat_khan_noor.shtml

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/18/executed

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noor_Inayat_Khan

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Bravery-Of-Noor-Inayat-Khan/

Leave a comment