In 1918, Germany lost the First World War. By the end of the war, uprisings and revolutions had broken out across the country. Many German revolutionaries followed the example of the revolution that had erupted in Russia in 1917, which led to a bloody civil war that lasted until 1922 and ended with the proclamation of the Soviet Union. In Germany, it did not go that far. With the help of the army, the communist revolutionaries were stopped. Instead of a communist utopia, a democracy emerged. The democracy was proclaimed in the quiet town of Weimar because Berlin was still too unsettled and dangerous. That is why Germany came to be called the Weimar Republic. The capital of the country remained Berlin.

A Turbulent Start

This first democracy had to begin under difficult circumstances. For example, the country had to cede large areas to neighboring countries as reparations for losing the First World War. These reparations were established in the Treaty of Versailles. The new democratic government had also been present when the peace treaty was signed but had little influence over the conditions. Since Germany had lost the war, “it had no choice but to sign,” according to the mindset of most French, British, and Belgian diplomats.

The Feeling of Betrayal: The “Stab-in-the-Back” Legend

In Germany, many believed that the uprisings and revolutions of 1918–1919 were not the result but the cause of the defeat. Germany had not seen much fighting during the First World War, and there had been few signs that the war was going poorly, due to wartime propaganda. Those who forced the emperor to abdicate through their revolution were blamed for the defeat and all the subsequent misery. Others blamed the Jews, who were often accused of communism. This idea became known as the “Stab-in-the-Back” legend. It is called a legend because the real defeat was indeed due to the military victories of the Allies and the German military leadership’s request for an armistice to prevent further losses.

Although part of the feeling of betrayal was based on distorted facts, Germans did have reasons to be dissatisfied with the Treaty of Versailles. They did not understand why they had lost the war and found it unfair that Germany was made solely responsible for the conflict. “Were most countries not equally eager for war as Germany was?” Especially the conservative elite—noble landowners, former officers of the imperial army, and civil servants from the empire—harbored deep hatred for the Treaty of Versailles and considered it a crime that the Weimar Republic government had accepted this “dictate.” They were generally unsympathetic to democracy and dreamed of a glorious empire once again. Clearly, under these political, social, and economic conditions, establishing a new democratic republic was a daunting task.

Many German men returned from the First World War physically and psychologically scarred. For them, “normal” life was impossible. Many would develop a deep hatred for anyone they considered responsible for the “betrayal of Versailles.”

The rich cultural life of the German Empire continued in the republic. New influences included political and ideological movements as well as technological advances. Films, for example, became longer after 1918 and gained sound starting in 1927.

The Politics

Although several new political parties emerged after 1918, the party system of the Weimar Republic displayed striking continuity with that of the Imperial era. The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), rooted in the working class, was the strongest political force between 1919 and 1932. It produced several Chancellors and the Republic’s first President, Friedrich Ebert, who served from 1919 to 1925. Despite this prominence, the SPD also spent considerable periods in opposition.

The Centre Party (Zentrum) regarded itself as the political representative of Germany’s Catholic population. It supplied the majority of Weimar Chancellors and participated in every governing coalition until 1932. The German Democratic Party (DDP), a centre-left liberal party — renamed the German State Party (DStP) in 1930 — played a key role in drafting the Weimar Constitution and was represented in most governments up to 1932.

The SPD, the Centre Party, and the DDP were unequivocally committed to parliamentary democracy and loyal to the Weimar Constitution. Together, they won around 70% of the vote in the January 1919 National Assembly elections. However, by the first Reichstag elections in June 1920, they had permanently lost their parliamentary majority. With the exception of a few Grand Coalitions, subsequent governments were typically minority coalitions of moderate liberal and conservative parties reliant on parliamentary toleration.

Nearly all Weimar governments were marked by chronic instability and short lifespans. Political parties remained deeply anchored in their original social constituencies and, given the limited capacity for redistributive reform, were often unwilling to compromise. From 1920 onward, most governments included the centre-right German People’s Party (DVP), which had initially viewed the Republic with scepticism. The Bavarian People’s Party (BVP), which split from the Centre Party in 1918, also joined many governing coalitions from 1922 onward.

A development that contributed significantly to the collapse of the Weimar Republic — and facilitated the rise of the NSDAP — was the steady decline of the liberal DDP and DVP. By the end of the Weimar era, both parties had been reduced to marginal splinter groups.

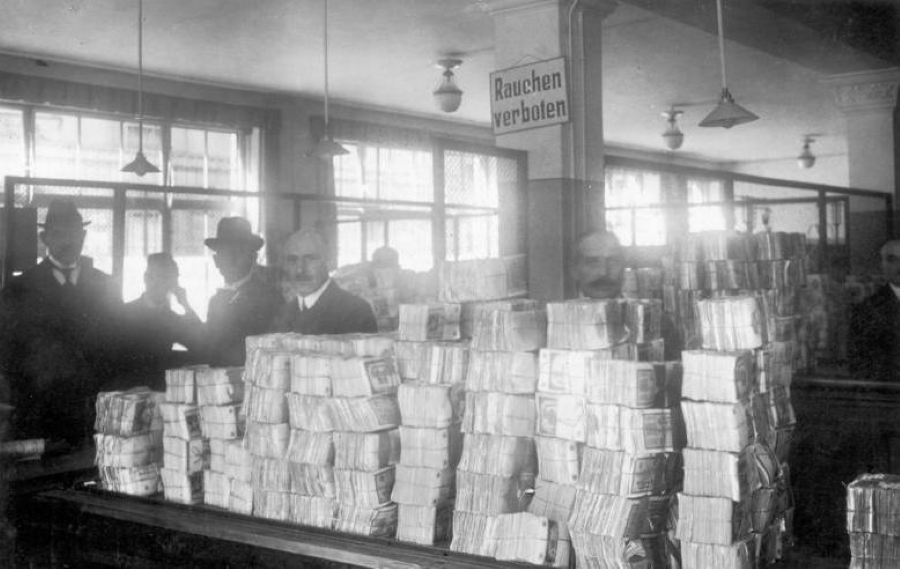

Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany

Hyperinflation affected the German Papiermark, the currency of the Weimar Republic, between 1921 and 1923, reaching its peak in 1923. Inflationary pressures had already built up during the First World War, when the German government financed much of its war effort through borrowing rather than taxation. By 1918, national debt had reached approximately 156 billion marks. This burden increased further after the war, when Germany was assigned reparations obligations totalling 50 billion gold marks under the May 1921 London Schedule of Payments, agreed in the aftermath of the Treaty of Versailles. These payments were to be made both in cash and in kind, for example through deliveries of coal and timber.

Inflation persisted in the immediate post-war years and intensified in 1921. In August of that year, the Reichsbank began purchasing foreign currency with paper marks at virtually any exchange rate. The official justification was to obtain hard currency for reparations payments, although in practice relatively little was paid in cash before 1924. The mark briefly stabilised in early 1922, but hyperinflation soon accelerated. The exchange rate fell from around 320 marks per US dollar in mid-1922 to approximately 7,400 per dollar by December. The collapse continued throughout 1923, culminating in November, when one US dollar was worth about 4.21 trillion marks.

The German authorities introduced several measures to halt the crisis. In late 1923, a new currency — the Rentenmark — was issued. It was backed not by gold but by mortgage bonds secured on industrial and agricultural land, which helped restore confidence. Monetary reform was reinforced by strict limits on further note issuance by the central bank. The Rentenmark was later replaced by the Reichsmark as the permanent national currency.

By 1924, the currency had stabilised, and reparations payments resumed under the Dawes Plan, which restructured Germany’s obligations and facilitated foreign loans. Because hyperinflation had effectively erased many nominal debts, legislation was introduced to revalue certain long-term obligations, such as mortgages, so that creditors could recover part of their losses.

Hyperinflation had severe social and political consequences, contributing to widespread hardship, resentment, and instability within the Weimar Republic. Historians and economists continue to debate its underlying causes, particularly the relative importance of reparations, war debts, fiscal policy, and monetary mismanagement.

A Flourishing Republic

The first years of the new republic were chaotic. The United States, in particular, watched the European continent with anxiety. At the beginning of the 1920s, the first signs of armed resistance against the “oppressors of Versailles” were already heard in Germany. In the United States, there was a conviction that another war would only lead to more destruction, which would benefit no one. In 1924, American bankers, led by Charles G. Dawes, came to Germany’s aid with loans: the Dawes Plan. Thanks in part to this plan, the German economy began to recover. Additionally, tensions with France were partially eased through the clever diplomacy of several German diplomats and government officials. The Weimar Republic promised to continue paying reparations. This reconciliation policy, which allowed the two countries to interact more normally, led to relative peace in Europe.

Thanks to the recovering economy, Berlin became one of the most attractive capitals in Europe. The city had a leading nightlife, was popular among artists, and hosted scientific research in its many university buildings. In parliament, democratic parties preferred to form coalition governments to achieve a majority. The Social Democrats were the largest party on average until 1930, followed by two liberal parties and a Christian Democratic party. There was also a conservative-nationalist party with relatively strong support. Although this party and its followers were not supporters of democracy, they sometimes still supported a Weimar government.

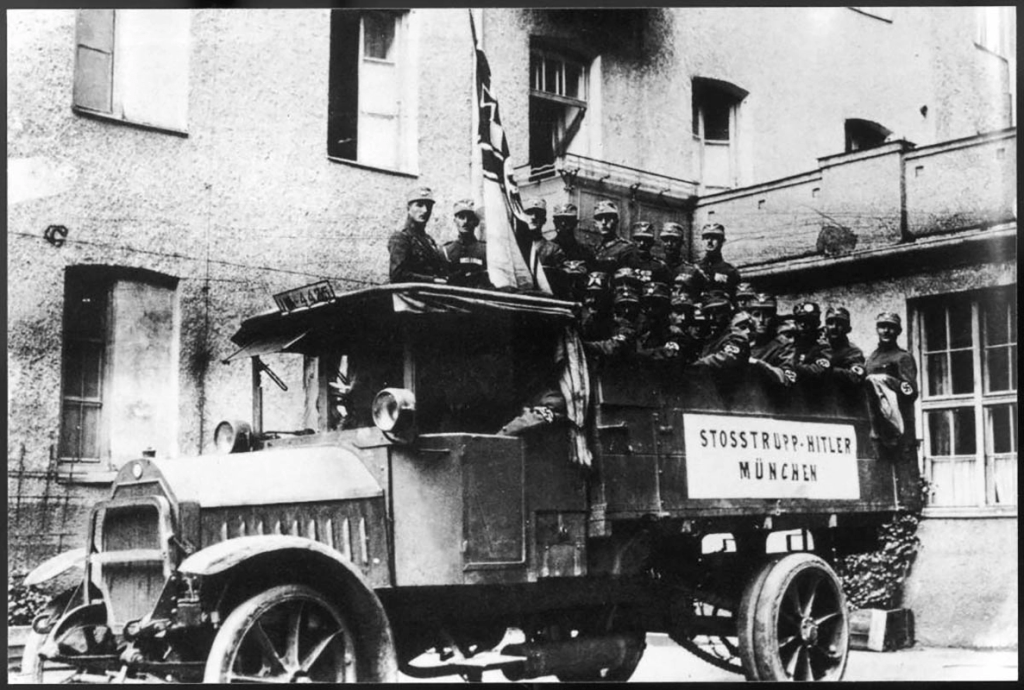

After 1933, the Weimar Republic headed toward the erosion of democracy. A young officer from the First World War would be responsible for this: Adolf Hitler.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weimar_Republic

https://www.britannica.com/place/Weimar-Republic

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-weimar-republic

https://www.thecollector.com/weimar-republic-hitler-rise-to-power/

https://www.bundestag.de/en/parliament/history/parliamentarism/weimar/weimar-200326

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment