When people hear or read the name of a concentration camp, they often assume there is only one camp. In fact, most main Camps had subcamps—Buchenwald had approximately 100 subcamps. (You can find the list of the camps at the end of this post.) This piece will show photographs of Buchenwald and some testimonies from survivors.

The photo above was taken by Willem Hoogwerf, a prisoner at Buchenwald. The following photographs were also taken by him and include his descriptions.

He was born on 24 January 1916 in Vlaardingen, the Netherlands. He trained and worked as a car mechanic. On 24 February 1941, he was arrested as a member of the Dutch resistance group, Geuzen. He was admitted to Buchenwald Concentration Camp as a political prisoner (Detention No. 5434) on 9 April 1941. There, he worked in the garages of the Commandant. In April 1945, he was liberated and returned to the Netherlands. He died on 3 August 2004 in Vlaardingen.

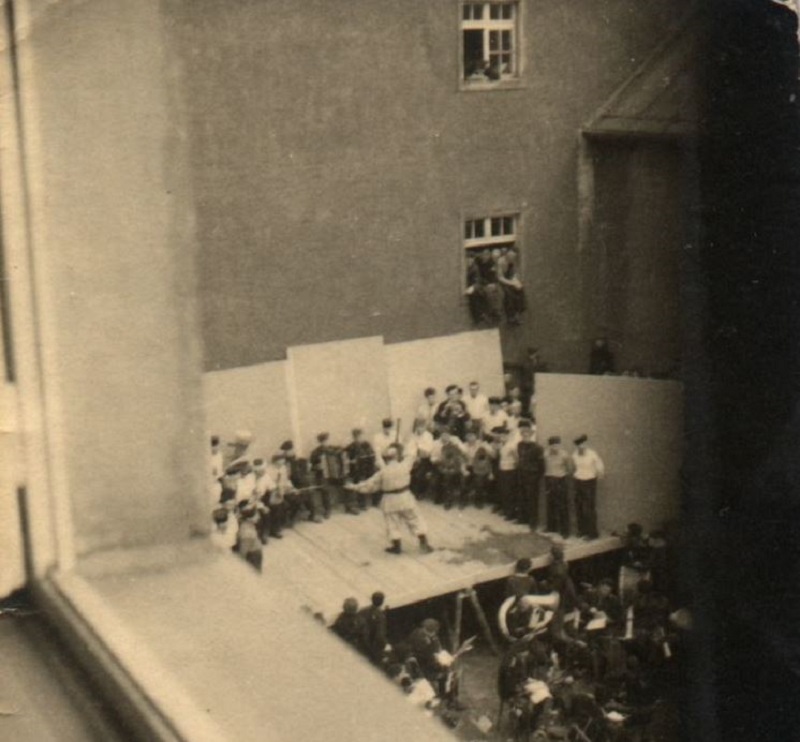

The description he gave for the photograph above:

“The gallows. On a rainy Sunday when the SS were bored, they made 100 prisoners to walk one after the other inside the fence and under the gallows. Everything had to stop at a whistle and those who stood under the gallows were hanged. During an execution the entire camp had to watch. Once, when 3 prisoners were being hanged, the camp commander thought the empty hooks were so untidy and had 3 of the forced spectators hanged as well. At least then all 6 hooks were used.”

“Camp Buchenwald, each barrack is surrounded by barbed wire. If typhus broke out in a barracks (lice), the gate would not open in the morning and typhus and hunger would take care of the rest.”

“In the right corner, the corpses are stripped of their clothes and thrown naked onto the wagon. The cremator awaits. This is part of a day’s harvest.”

“The gallows at the crematorium. In the background a mountain of cremation remains.”

Felix Müller

Felix Müller was born on 6 June 1904 in Leipzig. He was a construction worker and was admitted to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp as a political prisoner on 23 September 1943. After liberation on 11 April 1945, he returned to Leipzig. He passed away on 5 January 1962.

“View from a window in the effects room of a prisoner orchestra giving a concert for the camp inmates in front of the chamber building.”

Nina Andrejewskaja

“And there we stood for as long as we could still hear the shuffle of the wooden clogs.”

Nina Andrejewskaja was forced to look on as the German occupiers burnt her native city to the ground in the autumn of 1943. She was deported with her mother and sister to Saxony to perform forced labour, and there they were separated. The fifteen-year-old attempted to flee but was apprehended by the Gestapo. After interrogations and abuse, she was committed to the Ravensbrück concentration camp in the autumn of 1944. In Taucha, a Buchenwald subcamp, she was put to work manufacturing grenades. She managed to flee when the camp was cleared. She found her mother and sister near Chemnitz and returned home with them. She learned German and later worked for a German diplomat in Moscow.

The so-called Blood Road (Blutstraße) was the 5-km-long access road to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp built by inmates. At the beginning of mid-1938, the prisoners were forced to turn an old wooden road into a broad, concrete street.

Hundreds, many of them Jews, worked from dawn to dusk. Hungry, thirsty, and driven by blows from the SS, they carried construction materials on their shoulders from the quarry to the construction site. Work had to be carried out without proper tools and largely by hand. During the year-long construction period, inmates gave the new street its nickname, the Blood Road.

Beginning in April 1939, a regular bus line drove this Weimar-Buchenwald route and was accessible to the general public. Just in front of today’s memorial site portions of the cement street are visible and have been preserved in their original condition.

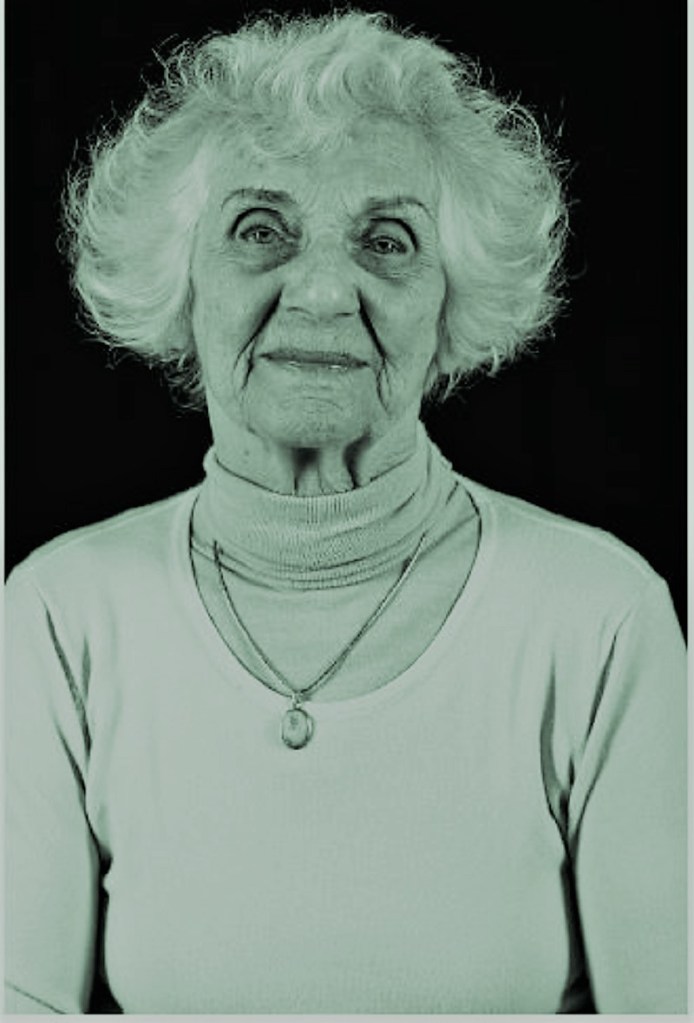

Éva Fahidi-Pusztai

“We did not even say goodbye to each other.”

Éva Fahidi was born on 22 October 1925 in Debrecen, Hungary, the daughter of the affluent middle-class timber merchant Desiderius Fahidi and his wife Irma Fahidi. In 1936, this Jewish family converted to Catholicism, and Éva and her sister attended the convent school. In the late 1930s, ever stricter anti-Semitic laws were introduced, increasingly excluding the Jewish population from society. When the German Wehrmacht occupied Hungary in the spring of 1944, the Fahidi family was forced to move to the ghetto. In late June, the Jewish population of the city was herded into a brick factory and deported to Auschwitz in several transports. On 27 June 1944, the Fahidi family was placed on the last transport—which took them to Auschwitz/Birkenau. Upon arrival, Éva Fahidi was separated from her mother and sister, who were both murdered in the gas chambers. Her father died soon afterward because of the conditions in the camp.

In mid-August 1944, Fahidi was transported along with 999 other Hungarian Jewish women to a subcamp of Buchenwald Concentration Camp to carry out forced labour. At Münchmühle near Allendorf, she was set to work producing shells.

While on a death march in March 1945, Fahidi was liberated by American troops; she returned to Hungary and worked in the export trade. She now lives in Budapest. She is a member of the Advisory Board of Former Inmates of Buchenwald Concentration Camp of the Buchenwald und Mittelbau-Dora Memorials Foundation and of the International Committee of Buchenwald-Dora and Subcamps. In 2012 she was awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, and in 2014 was made an honorary citizen of Stadtallendorf.

Éva Pusztai works, in part together with the Buchenwald Memorial, to ensure that the fate of the Jewish women is not forgotten. Current social and political developments in Hungary give added impetus to her efforts to oppose any reinterpretation of the annihilation of the Hungarian Jews and to bring about the conviction and sentencing of the last surviving criminals from the Nazi concentration and extermination camps.

“We are grandparents, and the fate of our grandchildren is what matters most to us. with four grandchildren, i myself have a stake in the future. the best i can wish for them – however utopian this may sound – is that they can create for themselves a life without fear. that they will build themselves a democratic society in which institutional hatred is unknown.”

The Subcamps

Sources

https://fotoarchiv.buchenwald.de/home

https://www.buchenwald.de/en/geschichte/biografien/bag-ausstellung

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_subcamps_of_Buchenwald

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment