Some people think I am Jewish, others think I am an atheist. In fact, I am neither, I am a New Apostolic Christian. But before I go into the main story, firstly a brief history and explanation of the church because it is not a well-known Christian faith.

The church has existed since 1863 in Germany and since 1897 in the Netherlands. It came about from the schism in Hamburg in 1863, when it separated from the Catholic Apostolic Church, which itself started in the 1830s as a renewal movement in, among others, the Anglican Church and Church of Scotland. The church ministers have no formal theological training. In addition to their family, professional, and social obligations, they perform their pastoral duties in an honorary capacity

However, this blog is not about the church but its situation during the Nazi era and also about one of its members who was murdered in Auschwitz.

It faced a complex relationship with the Nazi regime of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. Like many religious groups in Germany at the time, the New Apostolic Church had to navigate a precarious balance between adherence to its religious principles and the demands of the Nazi government.

The New Apostolic Church originated in the early 19th century as part of the larger Pentecostal movement, emphasizing the restoration of apostolic practices and spiritual gifts. By the time the Third Reich rose to power in the 1930s, the New Apostolic Church had established a presence in Germany and elsewhere.

Initially, the New Apostolic Church did not pose a significant challenge to the Nazi regime, and it did not draw the same level of attention or persecution as some other Christian denominations, such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses or the Confessing Church, which actively opposed Nazi policies. However, the New Apostolic Church did not fully align itself with the Nazi ideology either.

One key area of conflict between the New Apostolic Church and the Third Reich was the issue of allegiance. The Nazi regime sought to centralize power and control all aspects of German society, including religious institutions. This often led to conflicts with churches that refused to prioritize allegiance to the state over their religious beliefs.

The New Apostolic Church faced pressure to conform to the Nazi regime’s demands, including the incorporation of Nazi symbols and ideology into its practices. However, the church leadership generally avoided direct confrontation with the regime and sought to maintain a degree of independence.

While some members of the New Apostolic Church may have supported the Nazi regime, others resisted its influence or remained neutral. Individual experiences varied widely, with some facing persecution for their refusal to comply with Nazi demands, while others managed to coexist with the regime relatively peacefully.

Despite the challenges posed by the Third Reich, the New Apostolic Church survived the Nazi era and continued to exist after the fall of the regime. In the post-war period, the church, like many other religious organizations in Germany, grappled with questions of complicity, resistance, and reconciliation in the face of the horrors of the Holocaust and the crimes of the Nazi regime.

Harry Fränkel

Harry Fränkel was born on 27 April 1882 near Bremen in northern Germany. His parents, Salomon and Eliese Fränkel were Jewish. He converted and became the New Apostolic on 23 July 1908. In 1909 already he was a Sunday School teacher in Dortmund. In 1911 he was ordained as a Deacon and then, around 1922, as a Priest.

He was a successful textile merchant. He could afford to send his three children to college. And the family could afford domestic help. And then the year 1933 dawned—the year in which the Nazis seized power in Germany.

Under Persecution

Fränkel, a so-called full Jew because both parents were Jews, lost his job as managing director of the company Mayer & Günther. He started his own business. Advertisements in the German-language magazine Unsere Familie, for example, document this. In 1938, however, legislation forbade him from running his own business. His son Erich took over. Before long, he too was forbidden from carrying on with the business.

Meanwhile, Priest Fränkel was asked to suspend his ministerial activity—to protect the Church. Reprints of the choir folder omitted his name as a hymn writer. His son Harry Jr., a graphic designer and illustrator, was refused admission to the Academy of Arts. It was becoming harder and harder to find work for him. This is when Fränkel Sr. decided to emigrate.

On the Run

A first attempt was to take him to South Africa. Harry Fränkel wrote to Assistant Chief Apostle Heinrich Franz Schlaphoff, but he was unable to help. By decree, South Africa closed itself off to European Jews. The Apostle, however, gave him the address of a contact in Argentina.

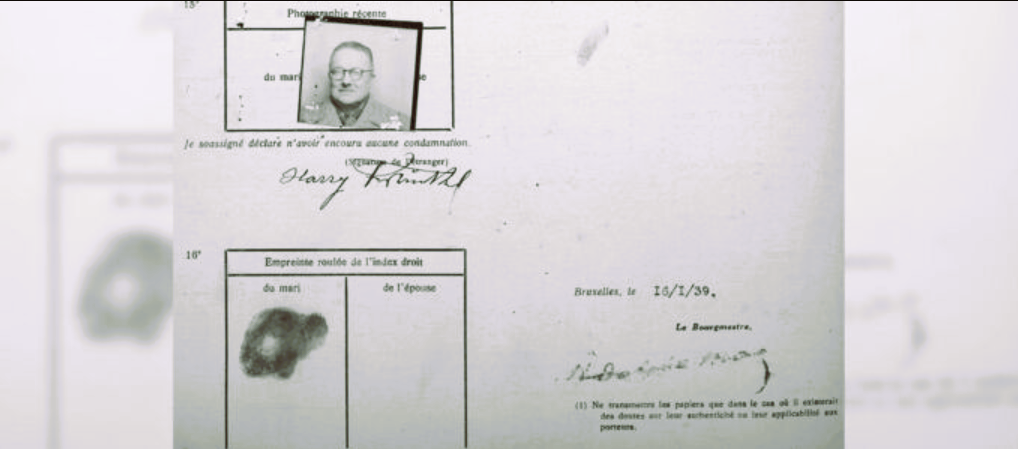

Belgium was the gateway to the free world at the time. The country was more liberal in terms of refugees than its European neighbours. For 17 months, Harry Fränkel lived in Brussels in five different locations—separated from his family, friends, and congregation. While he fought for permission to be able to stay in Brussels, the Gestapo, the secret police of the Nazi regime, knew of his whereabouts. And then came 10 May 1940, the day Germany invaded Belgium.

Deported and interned

Some 10,000 men were arrested in Belgium on that day because they were suddenly labelled as enemy foreigners and were considered a threat to the country. In a mass deportation, they were carted off to France by rail. There was hardly anything to drink in the overheated and overcrowded wagons, nothing to sit on or lie down on, no toilets…

This brought Harry Fränkel close to the French-Spanish border. First, he was taken to the Saint-Cyprien camp, Block 1, Barrack No I 42, and then to a place called Gurs, which was considered the most horrifying concentration camp in France. It was rife with hunger, cold, vermin, disease, and death. And then came the day when France surrendered to Germany, on 22 June 1940.

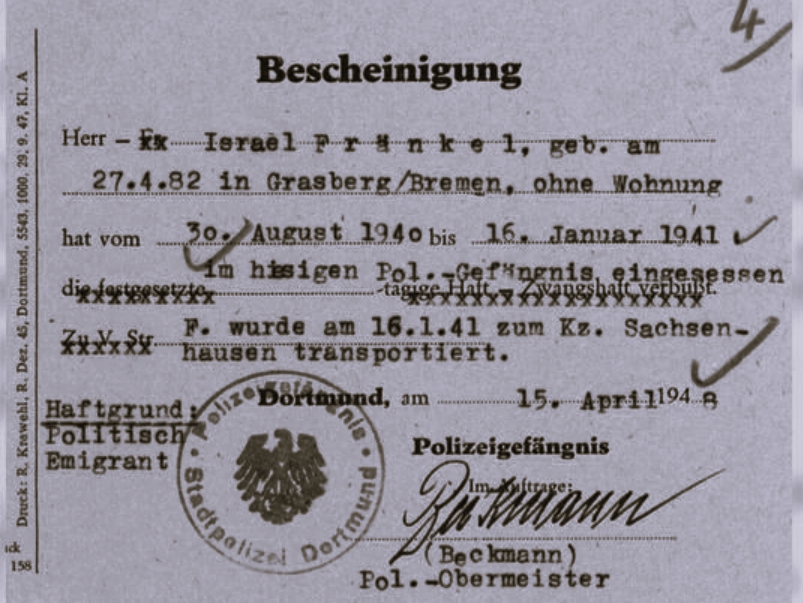

The armistice was followed by an extradition treaty. Harry Fränkel set out on his final journey. It took him via pre-trial confinement in Frankfurt (Germany) and the notorious Steinwache (a prison used by the Gestapo) in Dortmund—barely two kilometres away from his home and family—to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin and finally to Auschwitz.

Where he was murdered on 5 November 1942 at 8 a.m.: as per the International Holocaust Remembrance Center Yad Vashem. However, his name lives on, as the writer of the New Apostolic hymn, “Take off your shoes, for the place where you stand is holy.”

Sources

https://nac.today/en/a/1041771

https://nak.org/en/church/history

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donations

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment