I know that most people will know what the Holocaust is, but for some groups, it had a different name. In this blog, I try to explain some of the complexities.

The Holocaust stands as one of the most horrific and systematic genocides in human history. Occurring during World War II, from 1933 to 1945, the Holocaust was the Nazi regime’s deliberate and calculated extermination of six million Jews, alongside millions of others deemed undesirable, including Romani people, disabled individuals, Polish and Soviet civilians, political prisoners, and other minority groups. This essay explores the origins, implementation, and aftermath of the Holocaust, reflecting on its profound impact on humanity and the lessons it imparts.

The roots of the Holocaust can be traced to a toxic blend of long-standing anti-Semitism, nationalism, and the perverse ideology propagated by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. Hitler’s book, Mein Kampf, outlined his vision of a racially pure Germany and his virulent hatred towards Jews, whom he scapegoated for Germany’s social, economic, and political problems. When the Nazis rose to power in 1933, they began enacting a series of laws designed to disenfranchise, segregate, and ultimately eliminate Jews from German society. The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 legally codified racial discrimination, stripping Jews of their citizenship and prohibiting intermarriage between Jews and non-Jews.

The systematic execution of the Holocaust, known as the “Final Solution,” was a meticulously planned operation. The invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 marked a turning point, as mobile killing units called Einsatzgruppen began mass shootings of Jews and other targeted groups. This phase saw the transition from sporadic killings to a coordinated effort to annihilate the Jewish population.

The establishment of ghettos in occupied territories further isolated Jews, subjecting them to inhumane living conditions, starvation, and disease. The most infamous ghettos, like those in Warsaw and Łódź, were precursors to the extermination camps. The Wannsee Conference in January 1942 formalized the plan to systematically murder all Jews within reach of Nazi control.

Extermination camps, such as Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, Sobibor, and Belzec, became the central sites of mass murder. These camps utilized gas chambers, crematoria, and forced labor to kill millions efficiently. Auschwitz alone accounted for the deaths of over a million Jews. The industrial scale of the Holocaust was unprecedented, reflecting a chilling level of bureaucratic organization and cruelty.

The end of World War II in 1945 brought the liberation of the remaining concentration camp survivors by Allied forces. The full extent of the Holocaust’s atrocities was revealed, shocking the world and prompting a reevaluation of humanity’s moral compass. The Nuremberg Trials held Nazi leaders accountable, establishing a precedent for prosecuting crimes against humanity.

Shoah

The biblical word Shoah (שואה), also spelled as Shoa and Sho’ah, meaning “calamity” in Hebrew (and also used to refer to “destruction” since the Middle Ages), became the standard Hebrew term for the Holocaust as early as the early 1940s. In recent literature, it is prefixed with Ha (“The” in Hebrew) when referring to the Nazi mass murders, for the same reason that holocaust becomes “The Holocaust.” It may be spelled Ha-Shoah or HaShoah, as in Yom HaShoah, the annual Jewish “Holocaust and Heroism Remembrance Day.”

The Porajmos

The Porajmos, also known as the Romani Holocaust, stands as one of the lesser-known but equally devastating chapters of the atrocities committed during World War II. This genocide targeted the Romani people, an ethnic minority spread across Europe, who suffered under the Nazi regime’s brutal policies. While the Holocaust primarily evokes images of the Jewish genocide, the Porajmos highlights the systematic persecution and extermination of the Romani, an event that remains overshadowed in historical discourse.

The Romani people, with their origins traced back to northern India, have a long history of migration throughout Europe. Over centuries, they faced marginalization, discrimination, and persecution. By the time the Nazis rose to power, the Romani were already stigmatized as social outcasts and viewed with suspicion by many Europeans.

The Nazi ideology, with its emphasis on racial purity, deemed the Romani as racially inferior and asocial. Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, spearheaded the efforts to classify the Romani racially, attempting to segregate the so-called “pure Gypsies” from those of mixed heritage. However, these pseudo-scientific distinctions ultimately gave way to widespread persecution irrespective of such classifications.

The Porajmos unfolded in various stages, beginning with systematic discrimination and escalating to mass murder. Initially, the Romani were subjected to forced sterilizations, social isolation, and deportations. The Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which stripped Jews of their rights, were later extended to include the Romani. They were deprived of their civil liberties, subjected to arbitrary arrests, and confined to ghettos.

The invasion of Poland in 1939 marked a significant escalation. The Romani, alongside Jews, were herded into ghettos and labor camps. With the launch of Operation Barbarossa in 1941, the mass shootings by Einsatzgruppen, mobile killing units, targeted Romani communities in the occupied Soviet territories. These actions were precursors to the more systematic extermination that would follow.

The most infamous symbol of the Porajmos is Auschwitz-Birkenau, where a designated “Gypsy family camp” was established. Conditions were horrendous, with overcrowding, starvation, forced labor, and medical experiments conducted by the notorious Dr. Josef Mengele. On the night of August 2, 1944, known as “Zigeunernacht” or “Gypsy Night,” nearly 3,000 Romani men, women, and children were murdered in the gas chambers. The estimate is that between 220,000 and 500,000 Romani people died during the Holocaust, though the exact numbers are uncertain due to incomplete records.

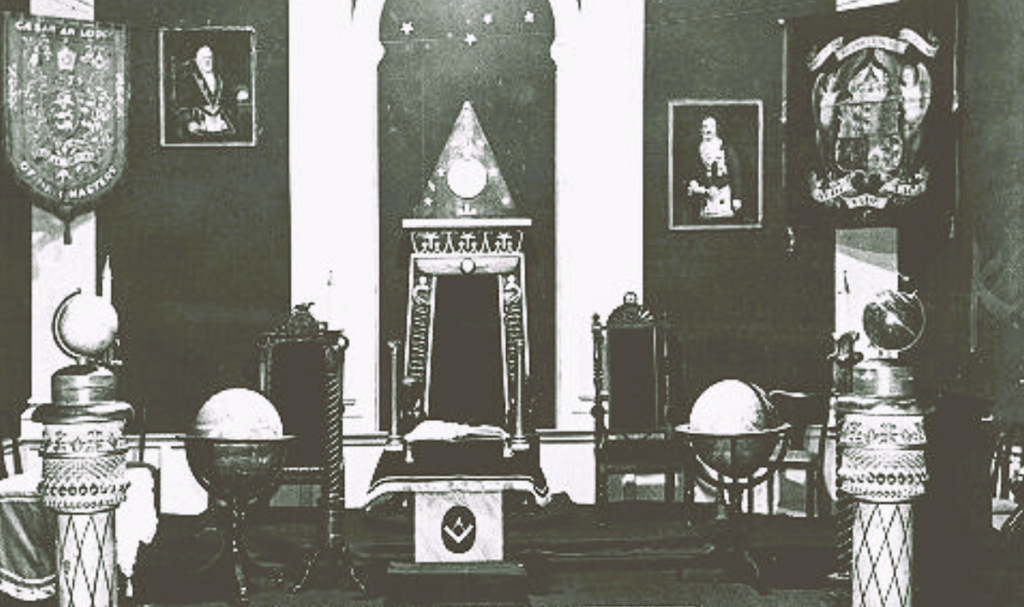

The Persecution of Freemasons

The persecution of Freemasons during the Third Reich is a lesser-known yet significant aspect of the broader campaign of terror and repression carried out by the Nazi regime. This period, marked by a systematic effort to eliminate perceived threats to Nazi ideology, saw the targeting of various groups, including Jews, political dissidents, and other minorities. Freemasons, whose principles of fraternity, liberty, and equality stood in stark contrast to the totalitarian and anti-democratic ethos of the Nazis, were among those who faced severe persecution.

The antipathy of the Nazi regime towards Freemasonry stemmed from a complex web of ideological, political, and social factors. Central to Nazi ideology was a belief in the existence of a global conspiracy orchestrated by Jews, often conflated with Freemasons, communists, and other perceived enemies. This belief was heavily influenced by the infamous forgery “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” which propagated the notion of a Jewish-Masonic plot to dominate the world. Hitler himself, in “Mein Kampf,” expressed his disdain for Freemasonry, alleging that it was a tool used by Jews to achieve their purported goals of world domination.

Freemasonry’s principles and practices further fueled Nazi hostility. The Masonic values of tolerance, enlightenment, and individual freedom were fundamentally at odds with the authoritarian and racially homogeneous society envisioned by the Nazis. The secrecy and international connections of Masonic lodges also aroused suspicion and paranoia among Nazi leaders, who viewed them as subversive organizations undermining the state’s authority.

The persecution of Freemasons in Nazi Germany began almost immediately after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. One of the regime’s first acts was to ban Masonic organizations and confiscate their properties. On April 7, 1933, Hermann Göring, one of Hitler’s top lieutenants, issued a decree dissolving Masonic lodges and appropriating their assets. This was followed by a series of measures aimed at eradicating Freemasonry from German society.

The regime’s propaganda apparatus also played a crucial role in demonizing Freemasonry. The Ministry of Propaganda, under Joseph Goebbels, produced and disseminated a vast array of anti-Masonic literature and media. Publications such as “Der Stürmer” and “Völkischer Beobachter” regularly featured articles attacking Freemasons, often depicting them as part of a broader Jewish conspiracy. Films, exhibitions, and pamphlets were used to educate the public about the alleged dangers posed by Freemasonry.

The repression of Freemasons involved both legal measures and direct violence. Many Masons were arrested, interrogated, and imprisoned in concentration camps. The Gestapo, the Nazi secret police, maintained detailed files on known Freemasons and actively sought to identify and neutralize them. Freemasons who held positions of influence or had connections with international Masonic bodies were particularly targeted.

In concentration camps, Freemasons were often marked with an inverted red triangle, distinguishing them from other prisoners. They were subjected to brutal treatment, forced labor, and, in many cases, execution. The exact number of Freemasons who perished during the Holocaust remains difficult to ascertain, but it is clear that they were among the many victims of the regime’s brutal policies.

The persecution of Freemasons during the Third Reich had a profound impact on the global Masonic community. In Germany, the destruction of Masonic lodges and the eradication of their members decimated the fraternity. Internationally, the persecution highlighted the resilience of Masonic principles in the face of tyranny and oppression. Many Masonic lodges outside of Germany provided support and refuge to their beleaguered brethren, reinforcing the values of solidarity and fraternity that are central to Freemasonry.

T4

The T4 Program, also known as Aktion T4, was a covert operation initiated by the Nazi regime in Germany aimed at systematically murdering individuals deemed “unworthy of life.” This program, which began in 1939, targeted the mentally ill, physically disabled, and other groups that the Nazis considered a drain on their utopian vision of a racially and genetically “pure” society. The T4 Program is not only a stark example of the extremes of eugenic ideology but also a precursor to the mass genocides that would follow in the Holocaust.

The roots of the T4 Program can be traced back to the broader eugenic movements that gained prominence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Eugenics, which advocated for the improvement of human genetic traits through selective breeding, found fertile ground in Germany, influenced by both local and international scientific discourse. The rise of the Nazi party brought these ideas into the political mainstream, with Adolf Hitler and other high-ranking officials expressing support for eugenic policies as part of their broader racial ideology.

Hitler’s personal commitment to these ideas was evident in his writings and speeches, where he frequently referred to the need to rid society of its “defective” elements. The onset of World War II provided the regime with both the cover and the logistical capacity to implement such radical policies on a large scale.

The T4 Program was officially initiated in 1939, following a secret decree signed by Hitler. The program was named after the address of its coordinating office, Tiergartenstraße 4, in Berlin. Under the guise of medical care, thousands of patients in psychiatric hospitals and care homes were subjected to systematic extermination.

The methodology of the T4 Program evolved over time. Initially, patients were killed through lethal injection and starvation. However, these methods were deemed inefficient. Subsequently, gas chambers were introduced, marking a chilling escalation in the program’s lethality. These gas chambers, disguised as shower rooms, used carbon monoxide gas to asphyxiate victims. This method not only allowed for the killing of large numbers of people at once but also foreshadowed the industrial-scale extermination techniques later employed in the Holocaust.

Despite the regime’s efforts to maintain secrecy, the T4 Program did not go unnoticed. Families of victims, church officials, and some medical professionals raised objections. Among the most vocal critics was Clemens August Graf von Galen, the Bishop of Münster, who delivered a series of sermons in 1941 condemning the program. His denunciations resonated widely, leading to public outcry and putting pressure on the Nazi leadership.

In response to the growing opposition, Hitler officially ordered the cessation of the T4 Program in August 1941. However, the killings did not entirely stop. Instead, the methods and infrastructure developed during the T4 Program were integrated into the broader genocidal machinery of the Holocaust, including the Aktion Reinhard camps and other extermination facilities.

The memory of the T4 Program has been preserved through various means, including memorials, museums, and scholarly research. It serves as a stark reminder of the consequences of unchecked power and the importance of vigilance against the resurgence of similar ideologies. In contemporary discussions about bioethics, disability rights, and human rights, the T4 Program is often cited as a historical example of the dangers posed by eugenic thinking and the imperative to uphold the dignity and worth of every individual.

Homosexuality and the Holocaust

The Holocaust, the systematic extermination of six million Jews by Nazi Germany, also targeted numerous other groups deemed undesirable by the Nazi regime. Among these were homosexuals, particularly gay men, who faced brutal persecution under Adolf Hitler’s regime. Understanding the plight of homosexuals during the Holocaust sheds light on the broader scope of Nazi oppression and the lingering effects of this dark period on LGBTQ+ communities.

Nazi ideology was grounded in a vision of racial purity and societal uniformity, heavily influenced by the pseudo-science of eugenics. Homosexuality was perceived as a threat to this vision for several reasons. First, it was seen as a degenerate behavior that undermined the moral fabric of the Aryan race. Second, homosexual men, in particular, were viewed as failing to fulfill their biological duty to procreate and thus perpetuate the Aryan lineage. Heinrich Himmler, a key architect of the Holocaust, explicitly linked homosexuality with racial decay, asserting that it would lead to the end of the Germanic people.

The legal foundation for the persecution of homosexuals was Paragraph 175 of the German penal code, which criminalized homosexual acts between men. Under the Nazi regime, this law was broadened and enforced with unprecedented severity. Gay men were subject to surveillance, arrest, and imprisonment. Approximately 100,000 men were arrested for homosexuality between 1933 and 1945, with around 50,000 of these sentenced to prison or concentration camps.

In concentration camps, homosexuals were identified by a pink triangle, a marker that often subjected them to particularly harsh treatment from both guards and fellow inmates. They were frequently assigned the most grueling labor and suffered extreme physical and sexual abuse. The death rate among homosexual prisoners was extraordinarily high, with estimates suggesting that as many as 60% did not survive.

The persecution of homosexuals during the Holocaust was characterized by a form of double marginalization. Firstly, they were ostracized within the broader society for their sexual orientation. Secondly, within the concentration camps, they were further marginalized by other prisoner groups. This dual stigmatization exacerbated their suffering and isolation.

The fate of lesbian women under the Nazi regime, though less systematically targeted, also warrants attention. Lesbians were not prosecuted under Paragraph 175, and thus their experiences varied. Some were arrested for other political reasons or for being “asocial,” while others were left relatively undisturbed. However, like all women in Nazi Germany, they were subject to the regime’s broader misogynistic and homophobic ideologies.

The end of World War II did not bring immediate liberation for homosexuals. Many who had been imprisoned under Paragraph 175 were not recognized as victims of Nazi persecution and continued to be seen as criminals under post-war German law. This legal and social stigma persisted for decades, delaying justice and recognition for the survivors.

The Nazis persecuted other groups, but I believe this to be a comprehensive overview.

Sources

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/euthanasia-program

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/gay-men-under-the-nazi-regime

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/tags/en/tag/freemasonry

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment