“Dolle Dinsdag” or “Mad Tuesday,” which occurred on September 5, 1944, was a pivotal and chaotic day in the Netherlands during World War II. The day is remembered for the widespread belief among the Dutch population that liberation from Nazi occupation was imminent, leading to scenes of jubilation, panic, and disarray. This essay delves into the historical background, the events leading up to Dolle Dinsdag, its significance during the war, and its aftermath, all of which illustrate the complexities of the Dutch experience in World War II.

Background: The Netherlands under Nazi Occupation

When Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands on May 10, 1940, it was a swift military campaign. Despite resistance, the Dutch government was forced to surrender five days later after the Luftwaffe bombed Rotterdam, and Queen Wilhelmina fled to London to form a government-in-exile. For the next four years, the Dutch lived under German occupation, which grew increasingly oppressive as the war progressed.

The Nazi regime imposed a brutal system of repression, mainly targeting Jews, resistance groups, and anyone suspected of opposing the occupation. The Dutch economy was heavily exploited for the German war effort. By 1944, food shortages were severe, leading to widespread suffering. As the Allies began making significant progress against the Axis forces, hope for liberation started to rise among the Dutch people, setting the stage for Dolle Dinsdag.

The Catalyst: Allied Advances in 1944

The primary catalyst for Dolle Dinsdag was the success of the Allied forces during the summer of 1944. The D-Day landings on June 6, 1944, marked the beginning of the liberation of Western Europe. The rapid Allied advance through France, combined with the collapse of German defenses, gave the Dutch new hope.

By September 1944, the Allied forces had liberated much of France and Belgium. The British and American armies, under the leadership of generals like Dwight D. Eisenhower, Bernard Montgomery, and Omar Bradley, pushed the Germans into retreat, and the front lines approached the southern border of the Netherlands. News of the liberation of Brussels on September 3, followed by the rapid Allied advance towards the Dutch border, created a surge of optimism.

A critical factor contributing to Dolle Dinsdag was a BBC broadcast on September 4, 1944, that reported the Allies were close to the Dutch border and might enter the Netherlands any day. Though this information was premature and somewhat exaggerated, it led to a widespread belief among the Dutch that liberation was imminent.

The Events of Dolle Dinsdag

The news spread like wildfire throughout the country, setting off what came to be known as Dolle Dinsdag, or “Mad Tuesday.” People across the Netherlands, in towns and cities alike, believed that Allied forces were only hours away from liberating them from four years of brutal occupation. Spontaneous celebrations broke out as Dutch citizens poured into the streets, waving flags, singing songs, and welcoming what they assumed would be an immediate end to the war.

Joy and Optimism

- For many Dutch people, the long years of suffering, persecution, and hardship appeared to be over. Residents began taking down black-out curtains, a symbol of the occupation’s suffocating presence, and put out orange banners in honor of the Dutch royal family. Resistance members and those who had been hiding, particularly Jewish citizens and people in hiding for forced labor reasons, came out into the open.

- Some local collaborators feared the coming of the Allies and quickly fled, seeking refuge in Germany or attempting to hide among the population. Resistance fighters, encouraged by the belief that liberation was near, became more active in sabotaging Nazi efforts.

Panic and Chaos

- For the Germans and their Dutch collaborators, the events of Dolle Dinsdag caused panic. Many German soldiers and NSB (National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands) members fled the country, fearing Allied retribution. The Dutch Nazi leader, Anton Mussert, along with others in his regime, were convinced that their cause was lost. Thousands of collaborators scrambled to pack their belongings and escape, abandoning posts and government positions.

- The resulting chaos led to the disruption of local governance as Nazi officials abandoned their offices. Even the civil police became paralyzed by confusion. German soldiers retreated or defected in various directions, some even throwing away their uniforms to avoid detection. Train stations were packed with people, with long lines of retreating Germans adding to the disarray.

Premature Celebrations

- Despite the euphoria, no Allied forces actually arrived on September 5, 1944. The Allies were still several weeks away from mounting a major operation aimed at liberating the Netherlands. This left the Dutch population in an awkward and vulnerable position, having celebrated too soon. Resistance fighters and those who had revealed themselves were exposed to reprisal, while collaborators who had fled returned emboldened, leading to a backlash against those who had been premature in their celebrations.

For some Jews who emerged from hiding, Dolle Dinsdag had disastrous consequences. When it became clear that the Allies were not yet arriving, the Nazi occupiers and Dutch collaborators, who had initially panicked, began to regroup. Jewish people who had exposed themselves, assuming that liberation was imminent, were suddenly vulnerable to arrest. In some cases, those who had harbored Jews were also exposed, leading to betrayals or increased risk of discovery.

The SS and other Nazi authorities realizing their control had not yet wholly collapsed, imposed brutal reprisals on suspected resistance fighters, hidden Jews, and those who had aided them. Fearful of losing their grip on the country, the Nazis intensified their crackdown on the Jewish population and resistance members, conducting more raids and arrests in the weeks following Dolle Dinsdag.

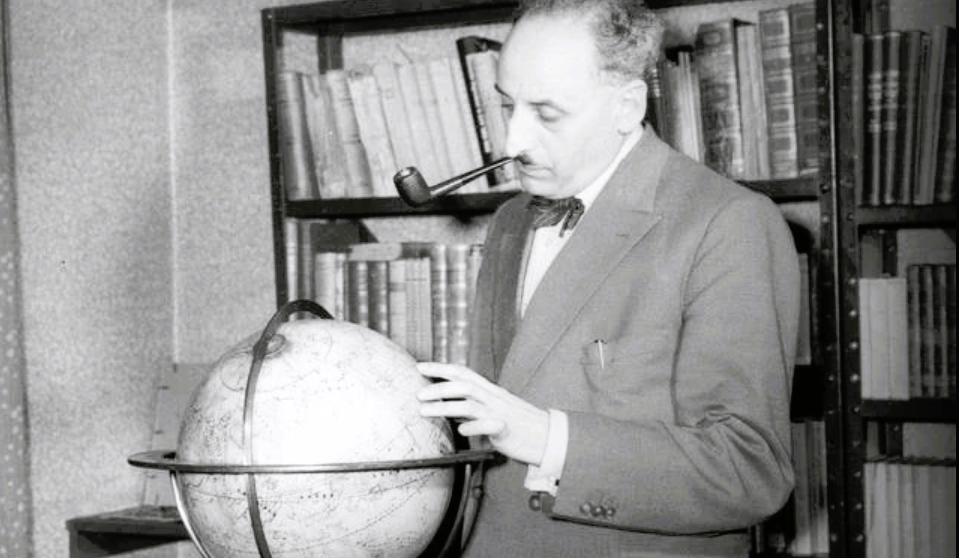

Hans Freudenthal’s escape on Dolle Dinsdag

The panic that Dolle Dinsdag caused among German officials and Dutch collaborators reverberated in Westerbork as well. Reports suggest that some German personnel stationed at the camp began preparing for a potential retreat, contributing to a sense of confusion. 8,000 NSB members( Dutch Nazis) and their families were housed in Westerbork on September 5, 1944, probably so they could pretend they were victims in case the Allied forces arrived.

On September 5, 1944. At the German airfield Havelte, Jewish workers were dismissed. Among them was Hans Freudenthal, a mathematics teacher. He took the train back home to Amsterdam.

On Dolle Dinsdag (Mad Tuesday), the men were dismissed and mostly made their way home by walking, cycling, or taking the train, hiding the Star of David under their coats. Most men—often under pressure from their families—decided to go into hiding until the liberation. Hans Freudenthal was among them. It was not an easy journey, and he described it as follows:

“September 5th. Picked up by a car on the way, which already had three people fleeing, and one more joined us. Along the way, I was told that no trains were running, but this turned out to be untrue at the Meppel station. I sat in the toilet until departure. 9:15.

We departed on a Friesian train, leaving Zwolle at 12:35. There, a train with German civilians and soldiers, along with many FlAKs (Flugabwehrkanonen – anti-aircraft cannons), also left for the North. This train later caught fire near Dedemsvaart.

Our train stopped just past Wezep at 13:00. We got out and fled into the forest. A group of planes flew overhead. We had a fairly long opportunity to escape. Terrible shooting followed. We were fired at around 25 times during one major assault. Two were killed, one seriously injured, and three were lightly wounded. It was dreadful to witness. Dr. van Oldebroek arrived. The dead and injured had been too close to the locomotive. On the train was a children’s holiday group with 50 children and a woman with crutches.

Would there be another locomotive? Ours had been hit four to six times. We had little hope. Should we walk home from there? It would take days, and there wasn’t enough food. There were prisoners on the train guarded by four Maréchaussée—escapees. Everyone was fleeing. One had already jumped off the train in Beilen and escaped, as a Maréchaussée shot at his colleague.

At 17:10, a locomotive arrived for the old train, and the new train departed. We arrived at 19:12 and left again at 19:26 from Amersfoort. At 21:00, we reached Muiderpoort. It was very crowded. This unexpected train allowed many more people to escape, including those who had tried to travel from Amersfoort to Amsterdam via Utrecht but had to turn back at Maarsen due to bomb damage. The lines from Utrecht to Leiden and Utrecht to The Hague were also broken. Some people had walked from our train to Oldebroek and even to Nunspeet. Some never made it to the train.

The mood in Amsterdam felt as if the Germans were already gone. They were apparently fighting in Rotterdam. The Landwacht (national guard) shot at people who were still on the streets after 20:00.”

Why the Allies Did Not Arrive

Despite the hopes raised by Dolle Dinsdag, the Netherlands remained under Nazi occupation for several more months. The primary reason for this delay was the strategic decisions made by the Allied commanders. After the liberation of Belgium, the Allies focused on securing key ports like Antwerp to ensure supplies could flow to the advancing armies. This was critical for maintaining the momentum of their campaign.

Additionally, Operation Market Garden, launched later in September, was an ambitious but ultimately unsuccessful attempt to capture bridges across major rivers in the Netherlands and pave the way for a rapid advance into Germany. This operation was meant to bypass the heavily fortified Siegfried Line and liberate the Netherlands quickly, It fell short of its objectives, especially in Arnhem, where British paratroopers were trapped and defeated in what became known as the Battle of Arnhem.

As a result of these military setbacks, the northern part of the Netherlands, including major cities like Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and The Hague, remained under German control until the final months of the war in 1945.

Aftermath of Dolle Dinsdag

Dolle Dinsdag had significant consequences for the Dutch population and the German occupiers. For the Dutch, the premature celebrations left many disillusioned and fearful of retribution. The Nazi authorities, initially shaken by the sudden flight of collaborators, quickly reasserted control. They imposed harsh measures in response to the perceived loss of order, with increased arrests, executions, and a crackdown on resistance activities.

For the German occupiers, the day revealed the fragility of their hold on the Netherlands. Although they managed to restore order temporarily, the chaos of Dolle Dinsdag signaled the beginning of the end of their occupation. It was clear that the Dutch people were ready for liberation, and the resistance movement gained momentum in the months that followed, with support growing for acts of sabotage against German infrastructure.

The final winter of the occupation, known as the Hongerwinter or “Hunger Winter,” was one of the most tragic periods in Dutch history. As the Allies focused on other fronts and supply lines were cut off, the Dutch population faced severe food shortages. Thousands died from starvation and cold in the winter of 1944-45.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Dolle Dinsdag remains a significant event in Dutch history, symbolizing both the hope and despair of the final year of the German occupation. It marked the psychological turning point for the Dutch people, who began to believe that the end of the war was finally within sight, even though they would still endure months of suffering before liberation came.

The day also serves as a reminder of war’s unpredictability and the impact of rumors and misinformation on public sentiment. Dolle Dinsdag was a spontaneous event fueled by hope; it was also a moment of great vulnerability for the Dutch population.

Sources

https://westerborkportretten.nl/bronnen/dolle-dinsdag-in-kamp-westerbork

https://www.haagsetijden.nl/tijdlijn/de-wereldoorlogen/dolle-dinsdag

https://dvhn.nl/drenthe/Dolle-Dinsdag-80-jaar-geleden-29194065.html

https://www.liberationroute.com/pois/1537/perilous-discharge-from-havelte-jewish-labour-camp

https://www.annefrank.org/en/timeline/36/mad-tuesday-german-soldiers-and-collaborators-on-the-run/

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment