A needle hums, its bite inscribes,

More than ink, it brands their lives.

A sequence carved, devoid of name,

A silent scream in numeric shame.

The ink sinks deep, a cruel decree,

A name erased—humanity’s plea.

Flesh becomes a ledger’s page,

Etched in despair, grief, and rage.

Not a mark of pride but pain,

A scar that whispers what remains.

The calloused hand, the bitter blade,

A thousand souls in ash replayed.

Yet, in these lines, a paradox grows,

For, even as the dehumanized shows,

Each number bears a story untold,

A soul defying the freezing cold.

The numbers march in somber rows,

Like fading echoes of untold throes.

Yet even there, amidst the blight,

The spark of hope refused the night.

They stood as witnesses, fierce and true,

Though the world turned blind to what they knew.

Their lives—reduced to numbered tags,

But their spirits rose, though bodies sagged.

Now those numbers, ghosts—on skin,

Remind us of where hate begins.

A testament carved to never repeat,

To see the human in those we meet.

No needle hums, no fires burn,

But from these lessons, may we learn.

The numbers fade, the ink may die,

But memory stands where shadows lie.

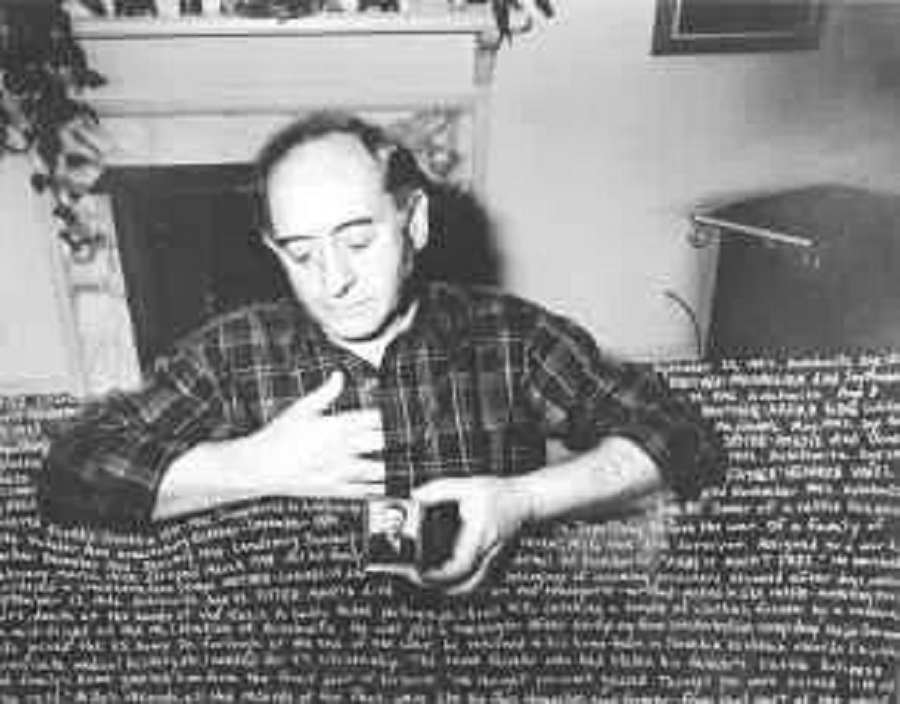

Below is the testimony of Miso (Michael) Vogel describing the arrival at Auschwitz

“So they marched us through the gate with whips and beatings and dogs jumping on us. We came to a huge brick building. They shoved us—shoved us into the huge brick building, and there were—prisoners and SS—telling us what to do next. It was tables, long tables. The first area was where we had to undress—strip our clothing. There were hooks behind us. You put the clothing through a piece of wire, hang the clothing up, take your shoes off, and put the shoes on the floor. Next table was the barbers, the camp barbers, who shaved our heads, cut our hair, and shaved our entire body. They said it’s for hygiene. Then we moved to another table—where the tattooing was done—the tattoo was done—on the left forearm. There was one person who would rub the—a little piece of dirty alcohol on your arm, and the other one had the—had the needle with the inkwell, and he would do the numbering. So my number is 65,316. That means there were 65,315 people numbered before me—tattooed before me. After the tattoo—tattooing was done—they put us where they gave us the clothing, but not what we came with. They gave us, issued us a striped brown cap, a jacket, a striped jacket, a pair of striped trousers, a pair of wooden clogs, and a shirt: no socks or underwear. Then the last area, when they gave us the uniform, they gave us two strips of cloth. The cloth, I would say, was about six inches long, maybe an inch-and-a-half wide, and it [was] star—starred with the Star of David, corresponding with the number on your left forearm, sewn on your left breast and also on the right pant leg. And then the last item, which was the most important item that we received, was a round bowl. And this bowl was the lifeblood of your being. First of all, without it, you couldn’t get the meager rations that we got. And second, the bathroom facilities were almost non-existent.”

Mr. Vogel died on 21 November 2000, aged 76.

Sources

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/id-card/miso-vogel

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/73637083/michael-miso-vogel

Leave a comment