Among the most dishonorable acts of art theft in history, the looting orchestrated by the Third Reich stands as the most colossal. By the end of World War II, Nazi forces had seized over 20% of Europe’s art. This cultural plunder was driven in part by the regime’s systematic assault on modernism and Adolf Hitler’s ambition to establish a grand “Führermuseum” in his hometown of Linz, Austria. Hitler envisioned this museum as the ultimate showcase for Europe’s most valuable and celebrated masterpieces. For the Nazi operatives to achieve their goals, they looted and hid countless artworks. They stored these items in various locations, including the Musée Jeu de Paume in Paris and Nazi headquarters in Munich. They concealed caches in caves and mines in Merkers, Altaussee, and Siegen.

This unprecedented assault on European culture spurred a critical Allied response. Volunteers, museum staff, and resistance members mobilized to safeguard treasures held in national institutions, as private collections were often left vulnerable to seizure. Art was quickly relocated from Paris’ Louvre Museum and other galleries and museums by the Nazis to secret locations to protect it from plunder. These sanctuaries included countryside monasteries and even a sprawling slate quarry in Wales—unlikely strongholds for protecting centuries of cultural heritage.

Despite these heroic efforts, the Nazis seized thousands of artworks from individuals and institutions. Many pieces ended up adorning the homes and offices of high-ranking Nazi officials. The fate of these looted masterpieces, from the chaos of World War II to their subsequent recovery—or loss—offers a compelling glimpse into the resilience of cultural preservation against the tide of destruction.

Dormant bank accounts, transfers of gold, and unclaimed insurance policies—seized by the Nazis and mainly hidden in Swiss bank accounts during World War II—have become focal points of economic and financial research. Simultaneously, museums and galleries are investigating the provenance of paintings, decorative arts, and sculptures in their collections to ensure none were looted during the war. Despite the Nazis’ reputation for meticulous recordkeeping, a significant number of stolen artworks remain missing and unaccounted for. While the Allied forces recovered many German records, do these documents truly unravel the stories behind individual art pieces? What is the complete narrative of the Allied efforts to trace the rightful owners of more than two million looted artworks and hold German art dealers and Nazi collaborators accountable?

In recent years, a surge of interest in Holocaust-era assets has driven heirs, art historians, and curators to confront these questions, delving into art provenance and claims research. Historically, few researchers explored the economic and financial aspects of the Nazi regime, and even fewer delved into Holocaust-related assets. Today, however, provenance research has become a critical endeavor for auction houses, art dealers, and museums. This renewed attention not only sheds light on unresolved histories but also seeks to restore justice and transparency in the art world.

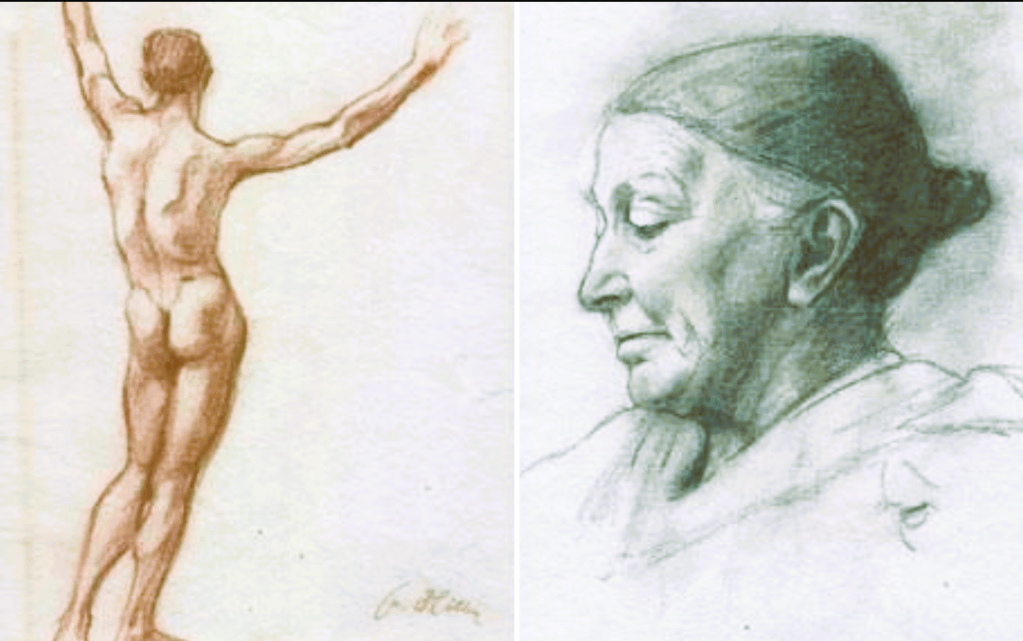

Adolf Hitler, a failed artist who the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts rejected, saw himself as a connoisseur of the arts.

In Mein Kampf, he vehemently denounced modern art, branding it as degenerate and a reflection of the moral decay of 20th-century society. He particularly despised movements such as Cubism, Futurism, and Dadaism. After becoming Chancellor of Germany in 1933, Hitler imposed his rigid aesthetic ideology on the nation. The Nazis exalted classical portraits and landscapes by Old Masters, especially those of Germanic origin, while labeling modern art as “degenerate.”

Under the Third Reich, modern art in Germany’s state museums faced destruction or sale, with proceeds directed toward Hitler’s grand ambition to create a European Art Museum in Linz. This museum was envisioned as a shrine to his curated vision of European culture. Meanwhile, high-ranking Nazi officials, including Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring and Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, exploited German military conquests to amass extensive private art collections, further fueling the regime’s plunder of Europe’s cultural treasures.

The systematic dispossession of Jewish people—along with the confiscation of their homes, businesses, artworks, financial assets, musical instruments, books, and even household furnishings—was a fundamental part of the Holocaust. In every country under Nazi control, Jews were systematically stripped of their possessions through a variety of methods facilitated by Nazi looting organizations. These actions were not only an extension of the regime’s genocidal policies but also a crucial means of consolidating wealth and resources for the Reich.

Key Aspects of Nazi Plunder

Targets

- Art Collections:

- Paintings, sculptures, and other artworks were seized from Jewish families, museums, and institutions.

- Works by prominent artists such as Rembrandt, Picasso, and Klimt were stolen.

- Degenerate Art Campaign: Nazis confiscated modernist and avant-garde art that they considered “degenerate.”

- Cultural and Religious Artifacts:

- Manuscripts, rare books, and religious items like Torah scrolls were targeted.

- Artifacts were taken from libraries, synagogues, and churches.

- Private Possessions:

- Jewelry, furniture, and other valuables were looted from Jewish homes, often following forced deportations.

- National Treasures:

- In occupied countries, the Nazis systematically plundered national museums and cultural institutions.

Organizations and Methods

- Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR):

- A Nazi task force led by Alfred Rosenberg focused on confiscating cultural property in occupied territories.

- Reichsbank and SS:

- Precious metals, jewelry, and other valuables were sent to the Reichsbank to fund the Nazi war effort.

- Looting of Jewish Property:

- The Nazis systematically cataloged and confiscated Jewish-owned assets as part of their racial policies.

- Transportation and Storage:

- Looted items were often transported to centralized repositories, such as the Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany and the Altaussee salt mines in Austria.

The Nazis systematically plundered cultural property across Germany and every occupied territory, with a particular focus on Jewish-owned property. This was executed through specialized organizations designed to identify and seize the most valuable public and private collections. Some artworks were earmarked for Hitler’s unrealized Führermuseum, while others were distributed to high-ranking officials like Hermann Göring or traded to fund Nazi activities.

In 1940, the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce for the Occupied Territories (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg für die Besetzten Gebiete, or ERR) was established, led by Alfred Rosenberg and Gerhard Utikal. The ERR’s first operational branch, the Western Agency (Dienststelle Westen), focused on France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, with its headquarters in Paris under Kurt von Behr. Initially, the ERR’s mission was to collect Jewish and Freemasonic books and documents, either to be destroyed or sent to Germany for further “study.” However, by late 1940, Hermann Göring—who effectively controlled the ERR—issued a directive to expand its operations. The ERR’s new mandate was to seize “Jewish” art collections and other valuable objects. These looted items were to be centralized in Paris, at the Musée Jeu de Paume, where art historians and staff inventoried the loot before it was sent to Germany.

Göring ordered that the spoils be divided between himself and Hitler. From 1940 to 1942, Göring visited Paris twenty times, where art dealer Bruno Lohse organized twenty exhibitions of the newly looted works, especially for Göring’s selection. At least 594 pieces were chosen for his personal collection. Lohse, appointed as a liaison officer and deputy leader of the ERR in March 1941, played a key role in facilitating the looting. Artworks not selected by Hitler or Göring were distributed to other Nazi leaders. Under the leadership of Rosenberg and Göring, the ERR seized a staggering 21,903 art objects from the occupied countries.

On 21 November 1944, at the request of Owen Roberts, William J. Donovan established the Art Looting Investigation Unit (ALIU) within the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). The unit was tasked with gathering intelligence on the looting, confiscation, and transfer of cultural property by Nazi Germany, its allies, and the individuals and organizations involved, with the ultimate goal of prosecuting war criminals and restituting stolen property. The ALIU compiled detailed reports identifying key suspects linked to art looting and Nazi policies of cultural theft. Interrogations were conducted in Bad Aussee, Austria, to uncover the extent of their involvement.

ALIU Reports and Index

The ALIU’s reports documented the networks of Nazi officials, art dealers, and other individuals who contributed to the Nazi spoliation of Jewish assets across occupied Europe. The final ALIU report consisted of 175 pages, divided into three parts:

Detailed Interrogation Reports (DIRs): These reports focused on individuals who played significant roles in the Nazi looting machine, including figures such as Heinrich Hoffmann, Ernst Buchner, Gustav Rochlitz, and Bruno Lohse.

Consolidated Interrogation Reports (CIRs): These reports outlined the art looting activities of Hermann Göring (the Göring Collection), the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), and the Linz Museum project.

Red Flag List: This list identified individuals involved in Nazi art spoliation across various countries, including Germany, France, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain, and more. The list also noted the status of these individuals—whether they were arrested, imprisoned, or remained at large.

Soviet Union

The Nazi plunder in Eastern Europe, particularly after the initiation of Operation Barbarossa, was extensive. In 1943 alone, Nazi forces sent millions of tons of resources back to Germany, including cereals, fodder, potatoes, and meat. However, the value of this plunder was comparatively low, largely due to the brutal scorched-earth tactics employed by both Nazi forces and retreating Soviet troops. By the end of the war, Nazi plunder in the Soviet Union included significant cultural losses.

In response, the Soviet State Extraordinary Commission for Ascertaining and Investigating the Crimes Committed by the German-Fascist Invaders was established on 2 November 1942. The commission cataloged extensive damage to Soviet cultural institutions, including 64 of the most significant museums, and reported that 173 museums in the Russian SFSR alone had been plundered. Looted items numbered in the hundreds of thousands, and the cataloging effort continued long after the war. In 2008, the Russian Federation’s State Commission for the Restitution of Cultural Valuables cataloged more than a million lost items, including artworks from prominent Russian museums and libraries.

The ERR and Nazi Looting in Eastern Europe

Under the leadership of Alfred Rosenberg, the ERR operated with the specific aim of collecting art, books, and cultural artifacts from occupied countries. As German forces retreated from Russia, the ERR’s operations expanded to include the seizure and transport of library collections to Berlin. The ERR’s teams were highly efficient, visiting hundreds of archival institutions, museums, and libraries across Eastern Europe. In total, they seized an estimated 100,000 geographical maps alone, for both academic and ideological purposes, as well as collector’s items.

The looting efforts in the Soviet Union were part of a larger network of confusion and competition among Nazi factions, including the German Army, the von Ribbentrop Battalion, the Gestapo, and individual officers. This often led to conflicts over authority and priorities, but the ERR teams continued their effective looting campaigns, contributing significantly to the Third Reich’s cultural theft.

Occupation of Poland and the Looting of Cultural Property

Following the German occupation of Poland in September 1939, the Nazi regime committed widespread atrocities against the Polish population, particularly targeting Polish Jews for genocide. In addition to this, the Nazis sought to eliminate the Polish upper classes and systematically destroy the nation’s cultural heritage. Art objects were looted on a large scale, as the Nazis had prepared a plan for cultural plunder even before the onset of hostilities.

Throughout the occupation, 25 museums and numerous other cultural institutions were destroyed. The total estimated cost of German Nazi theft and destruction of Polish cultural property is valued at $20 billion, which represents about 43 percent of Poland’s cultural heritage. More than 516,000 individual art pieces were stolen, including:

2,800 paintings by European artists

11,000 paintings by Polish artists

1,400 sculptures

75,000 manuscripts

25,000 maps

90,000 books, including over 20,000 printed before 1800

Hundreds of thousands of other items of artistic and historical value

To this day, many of the looted Polish artifacts remain in Germany. For decades, there have been ongoing negotiations between Poland and Germany regarding the return of this stolen cultural property.

Austria and the Looting of Art

After the Anschluss (the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany) on 12 March 1938, looting of Jewish properties began immediately. Churches, monasteries, and museums that had previously housed priceless art collections became prime targets for Nazi plunder. Among the looted properties was Ringstrasse, a prominent residential and cultural area from which art was confiscated.

Between 1943 and 1945, much of the looted artwork was stored in the salt mines at Altaussee, Austria. In 1944, about 4,700 pieces of art, including items from Austria and other parts of Europe, were held in these mines.

Führermuseum and Hitler’s Vision for Linz

Hitler’s vision for Linz, his hometown, was to transform it into the cultural capital of the Third Reich. He intended to build a series of museums and galleries, collectively known as the Führermuseum, to house the finest art treasures in the world. Hitler believed that Germany was entitled to claim these works, citing the looting that had occurred during the Napoleonic Wars and the First World War. The Führermuseum was intended to showcase art that Hitler considered to belong to Germany, many of which were looted from occupied countries.

The Hermann Göring Collection

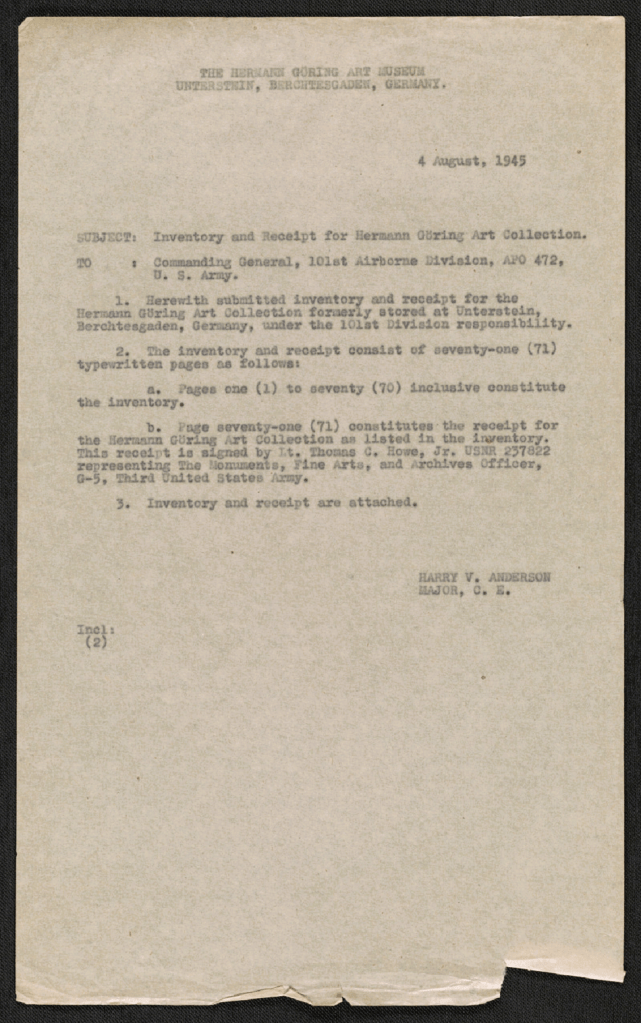

Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, a prominent Nazi leader, amassed an extensive personal collection of looted art, which came to be known as the Hermann Göring Collection. This collection represented approximately 50 percent of the works of art confiscated by the Reich from its enemies. Art dealer Bruno Lohse, who was also an adviser to Göring and a representative of the ERR in Paris, played a key role in assembling the collection.

By 1945, the Göring Collection included over 2,000 individual pieces, including more than 300 paintings. According to the US National Archives and Records Administration’s Consolidated Interrogation Report No. 2, Göring, unlike other Nazi officials, did not engage in overtly crude looting. Instead, he would often manage to create the illusion of legitimate acquisition by offering token payments or promises to the authorities overseeing the confiscation of the art. While Göring and his agents were not officially part of the German confiscation organizations, they utilized them to acquire artwork to the fullest extent possible.

Nazi Storage of Looted Art

Much of the looted art was stored at various locations across Europe, including in the salt mines of Austria. These sites were used to hide the stolen works from Allied forces during the war’s final years. These storage locations became crucial in the preservation and later retrieval of looted art after the war ended. Despite the best efforts of the Allies to recover as much art as possible, significant quantities of artwork remain missing or unaccounted for.

The Nazi regime under Adolf Hitler was notorious not only for its brutal policies of racial persecution and genocide but also for its systematic looting of cultural assets from occupied countries. During the Second World War, the Nazis pursued a wide-ranging plunder of art, books, and other valuable cultural objects with the aim of consolidating wealth for the Third Reich, strengthening its military effort, and fulfilling ideological goals.

Nazi Art Looting

The Third Reich’s obsession with art began as early as the 1930s, as Nazi ideologues sought to promote their vision of “Aryan” culture and eliminate what they considered “degenerate” art. Hitler envisioned a grand museum in Linz, Austria, to house artworks from Europe’s greatest collections, and Hermann Göring sought to enrich his personal collection. Art deemed “degenerate,” mostly modern works by Jewish, communist, and non-Aryan artists was confiscated from museums, galleries, and private collections across Europe. Paintings by artists like Picasso, Matisse, and van Gogh, among others, were either destroyed or sold to fund the Nazi war machine.

The Nazis also looted artworks from Jewish families and institutions. One of the most infamous cases involved the private collection of art dealer Paul Rosenberg. The Nazis seized hundreds of his paintings, many of which were later sold through approved art dealers or sent to storage in various locations, including salt mines and caves, for safekeeping. Much of Rosenberg’s collection remains missing to this day.

The Looting of Jewish Books

In addition to art, the Nazis sought to erase the cultural heritage of Jews by looting their books and religious texts. Jewish libraries and private collections were systematically raided across Europe. In France, for example, the Nazis took 50,000 books from the Alliance Israélite Universelle and thousands more from other Jewish institutions. These books were either destroyed, sold, or sent back to Germany. Similar plundering occurred in the Netherlands, Italy, and other occupied countries.

Repositories and Concealment of Looted Art

As the war drew closer to an end and the Allies advanced, the Nazis scrambled to hide their loot. Artworks were hidden in various remote locations, such as the salt mines of Merkers and Altaussee, where they were stored in conditions that preserved their integrity. These sites, along with others, became crucial repositories for thousands of looted objects. However, many works of art were never recovered or returned to their rightful owners.

Post-War Recovery and Restitution Efforts

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the Allies established special commissions, such as the Monuments Men, to track down and recover looted art and cultural objects. The recovery process was complicated, as many of the objects were dispersed across numerous hidden locations, and some had already been sold or transferred to private collections. One of the largest collection points for these looted objects was in Wiesbaden, Germany, where the Allies stored over 700,000 items, including paintings, sculptures, and other cultural treasures.

Efforts to return the stolen artworks were often hampered by bureaucratic obstacles, lack of proper documentation, and the complexity of identifying rightful owners, especially for those who had perished in the Holocaust. Organizations such as the World Jewish Restitution Organization and the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany played a crucial role in advocating for restitution. However, many works were never returned or returned only decades later.

The Continued Impact of Nazi Looting

Despite extensive efforts to locate and return looted artworks, many pieces remain missing, and some have surfaced in unexpected places. In 2012, a significant cache of around 1,500 artworks was discovered in the Munich home of Cornelius Gurlitt, the son of a Nazi-era art dealer. The collection included works by artists such as Marc Chagall and Henri Matisse, and many pieces are suspected to have been looted from Jewish families.

The issue of Nazi-looted art continues to affect the art world today. Museums and galleries around the world have increasingly become aware of the need to verify the provenance of their collections. This has led to greater scrutiny of the ownership history of artworks, particularly those acquired during the Nazi era. Institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago have posted lists of works with gaps in their provenance to encourage research and facilitate restitution efforts.

The Nazi Gold Train and Other Rumors

The search for looted Nazi treasures has also extended beyond art to rumors of hidden wealth, such as the legendary Nazi gold train. In 2015, two amateur explorers in Poland claimed to have found an armored train filled with gold, gems, and weapons hidden by the Nazis as they retreated. While some experts remain skeptical, the discovery of such alleged treasures highlights the ongoing fascination with and mystery surrounding Nazi loot.

Modern Restitution Efforts and Controversies

Since the 1990s, efforts to return looted art have intensified, with countries and institutions increasingly recognizing their responsibility to address the legacy of Nazi looting. In 1998, an international conference in Washington, D.C., sought to establish a global framework for handling Nazi-looted assets. As a result, many institutions, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, have reviewed their collections and worked to identify works that may have been taken during the Nazi era. This process continues today, with countries like Germany and Austria enacting laws to facilitate the restitution of looted cultural objects.

Despite these efforts, the process remains fraught with challenges. Many objects remain unaccounted for, and disputes over the rightful ownership of these objects continue to emerge. In some cases, museums and galleries have faced legal battles over artworks, with the descendants of original owners seeking to reclaim their cultural heritage.

Conclusion

The plundering of art and cultural objects by the Nazis represents one of the largest and most systematic thefts in history. Although efforts to recover and restitute these looted treasures have been ongoing for decades, much remains to be done. The legacy of Nazi looting continues to shape the art world today, and the restitution of these objects is not only a matter of legal and moral responsibility but also an ongoing quest to restore the cultural heritage of those who suffered under Nazi tyranny.

In August 1940, Samuel Hartveld and his wife, Clara Meiboom, boarded the SS Exeter in Lisbon, bound for New York. At 62, Hartveld, a successful Jewish art dealer, was leaving behind a world he once knew. The couple had fled their home city of Antwerp just before the Nazi invasion of Belgium in May 1940, parting from their 23-year-old son, Adelin, who chose to join the resistance.

Hartveld also bid farewell to a flourishing gallery housed in a stunning art deco building in the Flemish capital, a prized library, and more than 60 works of art. Though the couple survived the war, their son Adelin was tragically killed in January 1942. Hartveld was never reunited with his paintings, which were sold off at a fraction of their value to a Nazi sympathizer, and today they are scattered across galleries in northwestern Europe, including the Tate collection.

Hartveld’s lost paintings are but one example of the vast array of art looted, stolen, or forcibly sold after Adolf Hitler rose to power in 1933. Nearly 80 years after the end of World War II, a new book, Kunst voor das Reich, argues that Belgium has yet to confront this dark chapter of its history fully.

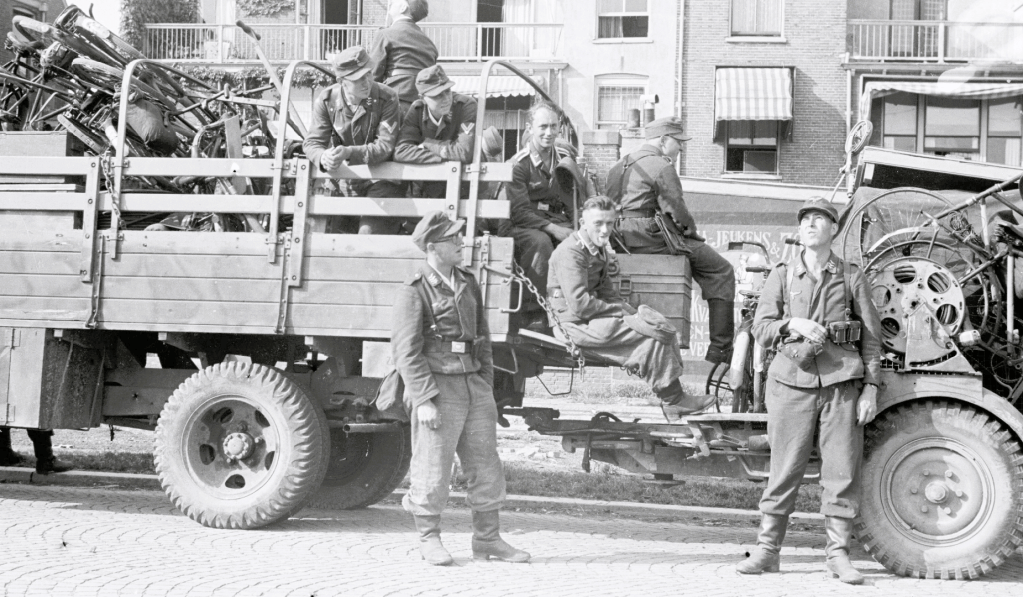

Even after they surrendered in the Netherlands, the Nazis were still looting.

German soldiers wait after their surrender at the moment of departure next to their fully loaded truck with partly stolen goods.

German soldiers depart after their surrender with horse-drawn carts full of requisitioned items, including bicycles.

It is important to note that more than 30,000 pieces of art remain missing. While many may have been destroyed, others could be hidden from the public eye or privately traded for substantial profit. Countless instances have seen restitution contested or rendered impossible, with the original owners of these masterpieces never living to witness their return.

Sources

https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/summer/nazi-looted-art-1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nazi_plunder

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20211123-the-masterpieces-stolen-by-the-nazis

https://kulturgutverluste.de/en/contexts/nazi-looted-cultural-property

Donations

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment