This blog is not intended to judge or assign blame. Instead, it aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the Holocaust by examining all aspects of that dark period, particularly the early days of the Third Reich. During this time, the Nazis successfully deceived many people, including those they would later persecute.

The Association of German National Jews and the German Vanguard: A Historical Perspective

A complex interplay of integration, identity, and confrontation with anti-Semitism marks the history of Jewish communities in Germany. Among the various Jewish organizations that emerged during the tumultuous interwar period, the Association of German National Jews (Verband nationaldeutscher Juden) and the German Vanguard (Deutscher Vortrupp) stand out for their unique ideological stance. These organizations advocated an alignment with German nationalism and, controversially, supported certain aspects of the Nazi regime, a position that continues to provoke scholarly debate.

Historical Background and Formation

The Association of German National Jews was founded in 1921 by Max Naumann, a German-Jewish lawyer. Its establishment reflected the belief held by some assimilated Jews that full integration into German society could be achieved by demonstrating loyalty to the German nation and its values. TheAssociation’s primary goal was to promote the assimilation of Jews into German culture, encouraging its members to downplay their Jewish identity in favor of embracing German nationalism.

Similarly, the German Vanguard, which emerged later in the interwar period, sought to position itself as a group of patriotic German Jews who aligned themselves with the broader goals of German revitalization. Both organizations rejected Zionism and distanced themselves from Jewish communal solidarity, arguing that such movements fostered separateness and undermined efforts at assimilation.

Ideological Stance and Controversial Alignments

The ideology of the Association of German National Jews was marked by an unwavering commitment to German patriotism and an often vocal opposition to other Jewish organizations. Its members sought to demonstrate their loyalty to Germany by criticizing Zionism, which they saw as antithetical to their assimilationist goals, and by supporting German cultural and political traditions. Max Naumann, in particular, was an outspoken critic of Jewish communalism and believed that Jews should fully identify as Germans above all else.

This approach led to controversial alignments with the rising Nazi Party during the early 1930s. Naumann and others in the Association believed that by demonstrating their patriotism and utility to the German nation, they could counter anti-Semitic prejudices. Astonishingly, the Association initially expressed support for some Nazi policies, interpreting them as a means to purge “foreign” elements from Jewish identity and to compel Jews to assimilate fully into German culture. However, this position was ultimately rooted in a tragic miscalculation of the Nazi regime’s intentions.

Decline and Disbandment

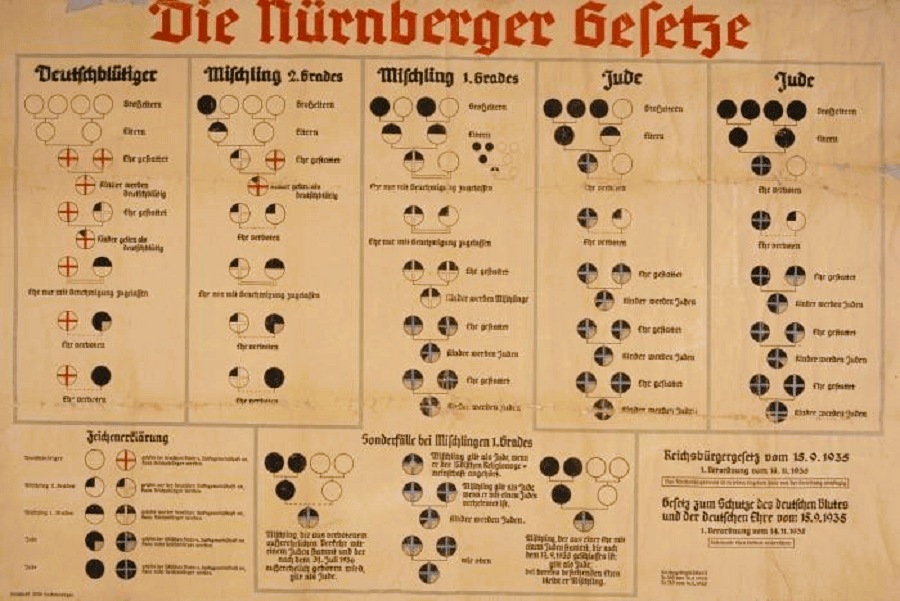

The rise of Adolf Hitler and the intensification of anti-Semitic policies in the 1930s rendered the goals of these organizations untenable. The Nazis did not differentiate between assimilated Jews and those who maintained distinct Jewish identities; all were subject to exclusion and persecution under the Nuremberg Laws and subsequent measures. The Association of German National Jews was officially disbanded in 1935 under pressure from the Nazi regime, which sought to eliminate all Jewish voices, regardless of their ideological stance.

Legacy and Controversy

The legacy of the Association of German National Jews and the German Vanguard is a contentious chapter in Jewish history. Their advocacy for assimilation and alignment with German nationalism represents a profound, if flawed, effort to navigate the challenges of anti-Semitism and integration. Scholars often view these organizations as illustrative of the diverse and sometimes conflicting responses of German Jews to the pressures of their time.

Critics argue that the association’s alignment with the Nazis was a grave error, reflecting a misunderstanding of the regime’s virulent and uncompromising anti-Semitism. However, others contend that the association’s efforts were born out of desperation and a genuine, albeit misguided, hope for a place in German society.

The Association of German National Jews and the German Vanguard highlight the complex dynamics of identity and survival faced by Jewish communities in interwar Germany. Their history serves as a sobering reminder of the dangers of assimilationist strategies in the face of rising totalitarianism and underscores the tragic consequences of misjudging ideological extremism. While their actions remain controversial, these organizations provide valuable insights into the struggles of minority communities to reconcile cultural integration with the preservation of dignity and identity in the face of persecution.

Hitler’s Jewish Generals

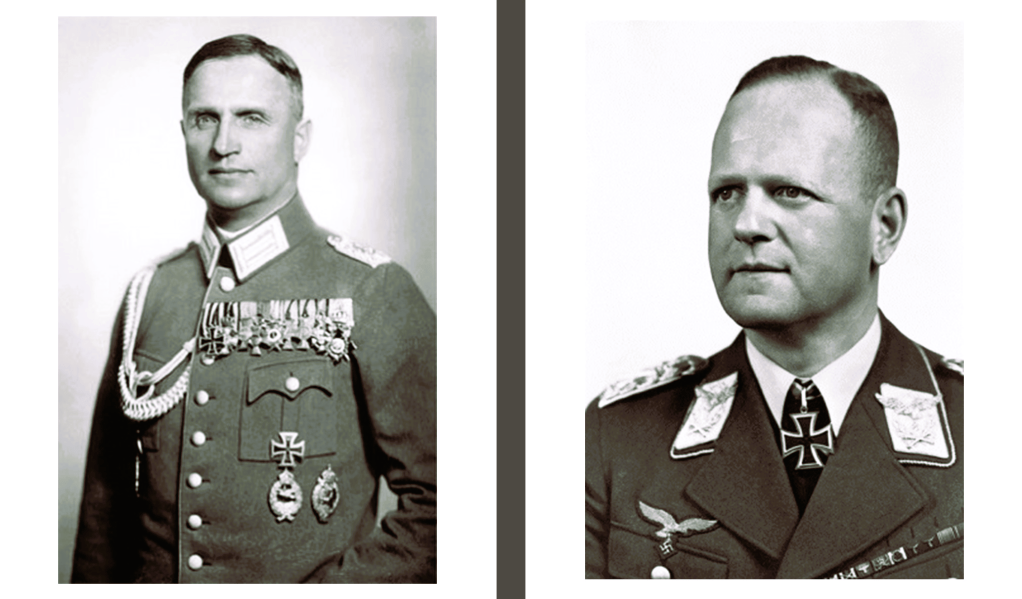

Erhard Milch (1892–1972) rose to the rank of Field Marshal and became known as the “Father of the Luftwaffe.” At eighteen, he joined the front lines as a gunner against the Russians and later transferred to the Air Force in 1915, serving against the French. Although not a pilot and without combat missions, he commanded squadrons by the war’s end.

After World War I, Milch transitioned to civilian aviation, eventually becoming Lufthansa’s manager. In the late 1920s, he joined the NSDAP, and after the Nazis seized power, he became Hermann Göring’s deputy as the Minister of Aviation.

In 1935, rumors arose that Milch’s father, Anton, was Jewish. Despite the Gestapo beginning an investigation, Göring intervened. To resolve the issue, Milch’s mother, Clara, signed an affidavit claiming she had an affair with an Aryan, Baron Hermann von Biron, who was the true father of her children. This declaration “proved” Milch’s Aryan heritage. Göring famously quipped, “Only I decide who is a Jew in my ministry and who is not!”

Less well-known is the story of Helmuth Wilberg (1880–1941), one of Germany’s pioneering fighter pilots. During 1917–1918, Wilberg commanded approximately seventy squadrons, and by the 1920s, he was recognized as the leading aviation theoretician in the Reichswehr. Göring initially sought to appoint General Wilberg as Chief of Staff of the Luftwaffe, but it was discovered that his mother was Jewish.

Unwilling to lose such a valuable asset, Göring declared Wilberg an “honorary Aryan” and entrusted him with developing the doctrine of the German Air Force. Wilberg played a key role in crafting the Blitzkrieg strategy and participated in the Polish campaign. He died in a plane crash in November 1941.

Sources

https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674931428

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Vanguard

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%206254.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Naumann

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1934/08/18/94557665.html?pageNumber=2

https://www.nli.org.il/en/a-topic/987007269402005171

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Association_of_German_National_Jews

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donations

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment