Eugene Bullard was an extraordinary figure in history whose courage, resilience, and determination helped him overcome significant racial and social barriers. He was not only the first African American military pilot but also a soldier, entertainer, and spy who played a significant role in both World Wars. Despite his achievements, Bullard’s story remained largely unrecognized in the United States for many years. His life serves as a testament to perseverance in the face of adversity and an inspiring example of a man who refused to be limited by societal constraints.

Early Life and Escape to France

Eugene Jacques Bullard was born on October 9, 1895, in Columbus, Georgia, to William and Josephine Bullard. Growing up in the racially segregated South, Bullard witnessed firsthand the discrimination and violence faced by African Americans. His father often told him stories about France, where Black individuals were treated with greater equality and dignity. Inspired by these tales, Bullard resolved to leave the United States and seek a better life in France.

At the age of 11, he ran away from home and traveled across the United States, doing odd jobs to support himself. Eventually, he stowed away on a ship bound for Scotland and later made his way to France. He found work as a boxer and circus performer, integrating himself into French society. The acceptance and opportunities he found in France affirmed his belief that he had made the right choice in leaving America.

Military Service in World War I

When World War I broke out in 1914, Bullard enlisted in the French Foreign Legion, determined to fight for his adopted country. He served with distinction in battles such as Verdun and was wounded multiple times. For his bravery, he was awarded the prestigious Croix de Guerre and Médaille Militaire, honors given for heroism in battle.

While serving with the 170th Infantry, Bullard was seriously wounded in action during the Battle of Verdun in March 1916. During his recovery, he took up flying on a bet. After regaining his strength, he volunteered on October 2, 1916

He’d soon get the nick name ‘The Black Sparrow’

Bullard sought to join the French Air Service. Although racial discrimination had prevented African Americans from becoming pilots in the United States, Bullard was accepted into the Aéronautique Militaire, making history as the first African American military aviator.

He flew numerous combat missions, engaging in dogfights against German aircraft and demonstrating exceptional skill and bravery. Despite his accomplishments, he was never permitted to join the United States Army Air Corps due to the racial policies of the American military at the time.

After the United States entered the war in 1917, Bullard attempted to join the U.S. Air Service but was denied. Officially, the rejection was due to his enlisted status, as the Air Service required pilots to be officers with at least the rank of First Lieutenant. In reality, racial prejudice within the American military was the true barrier. Bullard returned to the Aéronautique Militaire but was abruptly removed following an apparent confrontation with a French officer. He then rejoined the 170th Infantry Regiment until his discharge in October 1919.

Life Between the Wars

After World War I, Bullard remained in France, where he opened a successful nightclub in Paris. His club, Le Grand Duc, became a popular gathering spot for celebrities, artists, and intellectuals, including Josephine Baker, Louis Armstrong, and Ernest Hemingway. Bullard also became involved in the jazz scene, further cementing his place in the cultural fabric of France.

Bullard also founded Bullard’s Athletic Club, a gymnasium that offered physical culture training, boxing, massage, ping pong, and hydrotherapy. Additionally, he worked as a trainer for renowned boxers Panama Al Brown and Young Perez.

On July 17, 1923, he married Marcelle Eugénie Henriette Straumann (born July 8, 1901), a milliner from Paris’ second arrondissement. Their marriage ended in divorce on December 5, 1935, with Straumann relinquishing custody of their two children, Jacqueline Ginette and Lolita Joséphine, to Bullard.

When World War II broke out in September 1939, Bullard—who was fluent in German—was recruited by the French government to spy on German citizens who continued to frequent his nightclub

Contributions During World War II

When Nazi Germany invaded France in 1940, Bullard joined the French Resistance and fought against the advancing forces. He was wounded once again but managed to escape to Spain and later to the United States.

Return to the United States and Later Years

Despite his heroic service in France, Bullard faced racism and discrimination upon his return to the United States. He worked menial jobs, including as an elevator operator in New York City, far removed from the grandeur of his life in Paris. His contributions to history went largely unrecognized for decades.

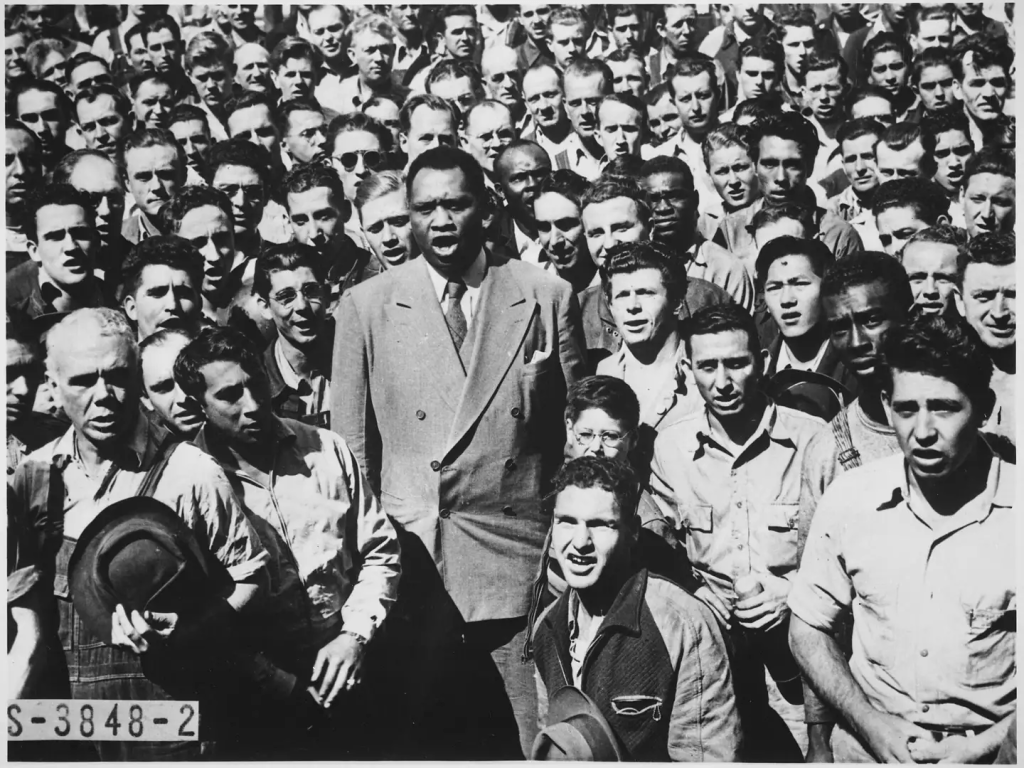

In 1949, a benefit concert by Black actor, singer, and activist Paul Robeson in Peekskill, New York, organized for the Civil Rights Congress, ended in violence known as the Peekskill riots. The unrest was partly instigated by members of the local Veterans of Foreign Wars and American Legion posts, who viewed Robeson as a communist sympathizer.

The concert was originally scheduled for August 27 at Lakeland Acres, north of Peekskill. However, before Robeson arrived, a mob attacked concert-goers with baseball bats and stones, seriously injuring thirteen people before police intervened. As a result, the event was postponed until September 4. While the rescheduled concert proceeded without incident, attendees were ambushed as they departed, facing a gauntlet of hostile locals who hurled rocks at their vehicles.

Bullard was among those brutally attacked after the concert. He was knocked to the ground and beaten by an enraged mob, which included members of state and local law enforcement. The assault was captured on film and later featured in the 1970s documentary The Tallest Tree in Our Forest and the Oscar-winning documentary Paul Robeson: Tribute to an Artist, narrated by Sidney Poitier. Despite clear evidence, none of Bullard’s attackers were prosecuted. Graphic images of Bullard being beaten by two policemen, a state trooper, and a concert-goer were later published in The Whole World in His Hands: A Pictorial Biography of Paul Robeson by Susan Robeson

In 1959, France honored Bullard by making him a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honor, the country’s highest military distinction. He also participated in ceremonies commemorating the contributions of foreign soldiers in France. However, his legacy remained largely ignored in the United States until decades later.

Eugene Bullard passed away on October 12, 1961. It was only posthumously that he began to receive recognition in his homeland. In 1994, the United States Air Force honored him with a symbolic commission as a second lieutenant, acknowledging his place in aviation history. His story has since been more widely shared, ensuring that his remarkable achievements are not forgotten.

Legacy and Impact

Eugene Bullard’s life is a powerful example of resilience, bravery, and an unyielding belief in justice. He broke racial barriers in military aviation, fought for a country that welcomed him when his own would not, and contributed significantly to the cultural and military history of both France and the United States. His story serves as an inspiration to future generations, highlighting the importance of perseverance in the face of adversity.

Though Bullard may not have received the recognition he deserved during his lifetime, his legacy continues to inspire those who learn about his incredible journey. He remains a symbol of courage and an enduring figure in both African American history and the history of military aviation.

sources

https://www.timesunion.com/history/article/peekskill-riots-paul-robeson-racism-18279119.php

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eugene_Bullard

https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/eugene-j-bullard

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/great-war-two-lives-eugene-bullard/

https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/eugene-bullard-1895-1961/

Donations

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment