The one thing that always baffled me is the vehement hate the Nazis had for Jazz music. It was considered “Entartete Musik”—degenerate music, a label applied in the 1930s by the Nazis to Jazz and also other forms of music.

I wrote a piece about Johnny & Jones before, this is not so much a follow-up as it is more of an enhancement to the previous blog. I felt it was important to remember those who were murdered for their art and their religious background.

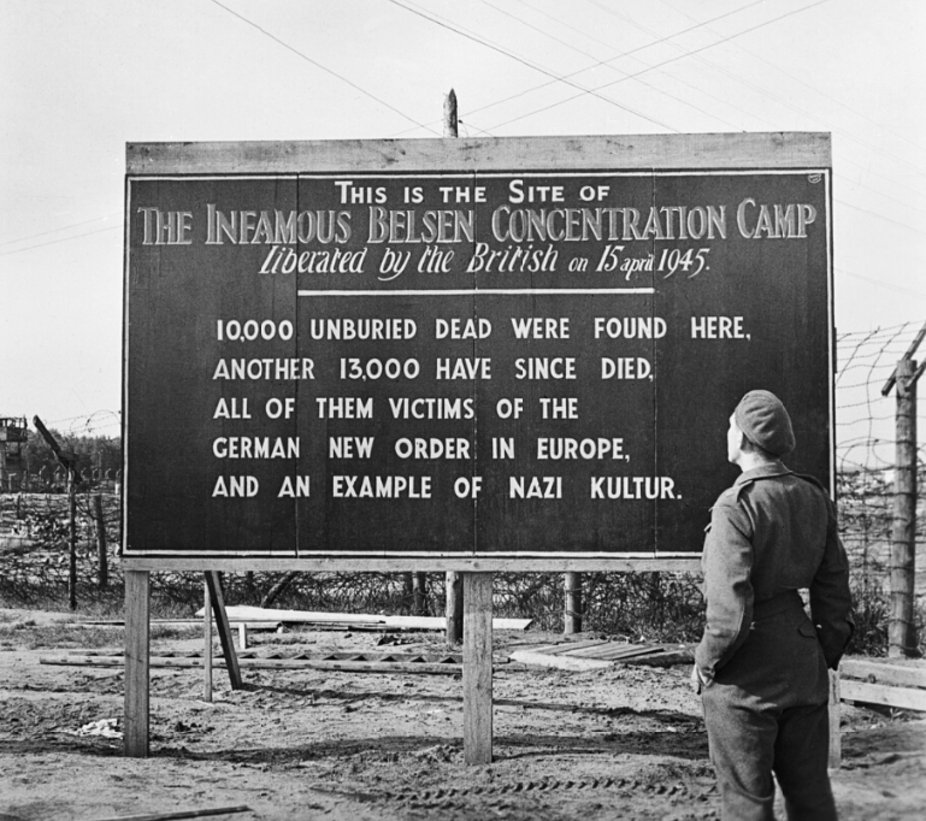

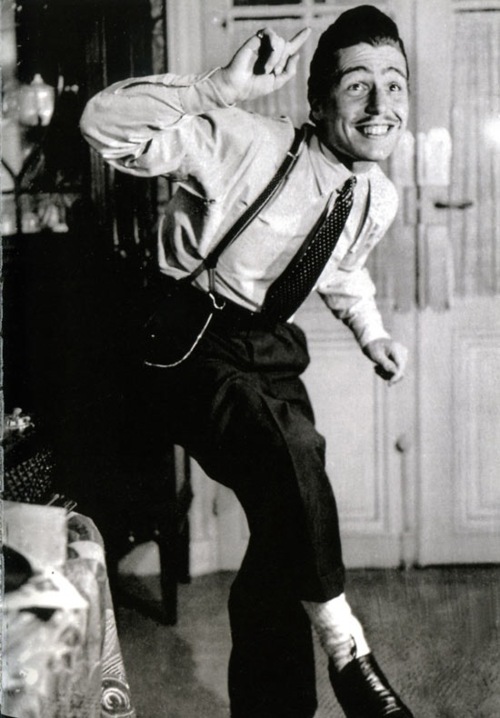

In the 1930s, the Amsterdam duo Nol (Arnold Siméon) van Wesel and Max (Salomon Meyer) Kannewasser, alias Johnny & Jones, were extremely popular— thanks, in part, to their first single hit, “Mister Dinges Weet Niet Wat Swing Is.” They were cousins and they accompanied themselves on the guitar. The musicians sang their swinging Jazz songs with smooth lyrics in a semi-American accent. Their careers come to an end when the two Jewish musicians were arrested by the Germans during World War II, and they were killed in the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp.

In 1934, The Bijko Rhythm Stompers performed in De Bijenkorf, the group consisted of Bob Beek, Max Kannewasser, Max Meents and Nol van Wesel. This was the first time that the collaboration between Max (Salomon Meijer) Kannewasser (24 September 1916/Jones) and Nol (Arnold Simeon) van Wesel (23 August 1918/Johnny) can be traced.

In 1936, Johnny & Jones started performing as a singing duo. They were discovered during a performance in the café/restaurant, Van Klaveren on the corner of Frederiksplein and Weteringschans. Shortly afterwards they quit their jobs at De Bijenkorf and entered the artistic profession. They became the first teenage idols soon after in the Netherlands.

They could be heard regularly in 1938 on VARA radio. They then performed as an interlude with “The Ramblers.” They recorded records for the record-label Decca, which was started in November 1938 with the song “Mister Dinges Does Not Know What Swing Is.” This song was their greatest success.

Initially, at the start of the war, Johnny & Jones were able to perform without much problem. For example, in February 1941 they performed at Amersfoort with “The Ramblers,” but by the end of 1941, this was forbidden for Jewish artists.

With growing pressure to go into hiding, their final performance was for a wedding reception of one of Arnold’s colleagues from de Bijenkorf (Dutch department store), Wim Duveen.

He was married to Betty Cohen at the main synagogue in Amsterdam in 1942. Salomon, in 1942, had married Suzanne Koster, a woman from the Dutch East Indies (Surabaya) and Arnold had married Gerda Lindenstaedt, also in 1942, a German refugee who had come to Holland in 1939.

The young men went into hiding with their wives at the Jewish nursing home Joodsche Invalide. The staff would hide them in an elevator between floors during inspections. When they were not hiding, they performed for staff and patients. Disaster struck on 29 September 1943 when the home was raided and its inhabitants sent to Westerbork.

Johnny & Jones were put to work there processing parts of crashed aircraft, including Plexiglas (source: Leo Cohen, a fellow prisoner in Westerbork). They found a place at the camp in the revue (consisting of excellent artists). Since only German-language performances were allowed, Johnny & Jones had to learn German and they had to have it well-mastered. Only then could they perform in March 1944 during a camp revue.

In August 1944, the two singers were allowed to leave the camp, with permission of the commandant, not only for their work disassembling parts but also to record songs in Amsterdam. In the NEKOS studios, they recorded six songs about their life in Westerbork, including “Westerbork Serenade.“

Ik geloof ik ben niet helemaal in orde

Ik ben met mijn gedachten er niet bij

Opeens ben ik een ander mens geworden

Mijn hart klopt als de vliegtuigsloperij

Ik zing mijn Westerbork serenade

Langs het spoorwegbaantje schijnt het zilveren maantje

Op de heide

Ik zing mijn Westerbork serenade

Mit einer schoene Dame, wandelend tezamen zij aan zijde

En mijn hart brandt als de ketel in het ketelhuis

Zo had ik het nooit te pakken bij mijn moeder thuis

Ik zing mijn Westerbork serenade

Tussen de barakken kreeg ik het te pakken op de hei

Dieser Westerbork liebelei

Dieser Westerbork liebelei

Daarna ging ik naar de saniteter

Die vent zei d’r is heus niets aan te doen

Maar je voelt je heel wat stukken beter

Na ‘t geven van de allereerste zoen (en dat moet je niet doen)

Ik zing mijn Westerbork serenade

Langs het spoorwegbaantje schijnt het zilveren maantje op de heide

Ik zing mijn Westerbork serenade

Mit einer schoene Dame

Wandelend tezamen zij aan zijde

En mijn hart brandt als de ketel in het ketelhuis

Zo had ik het nooit te pakken bij mijn mammie thuis

Ik zing mijn Westerbork serenade

Tussen de barakken kreeg ik het te pakken op de hei

Dieser Westerbork liebelei

Below is the translated text of the song.

I think I’m not quite right

I’m not there with my mind

Suddenly I became a different person

My heart beats like an aeroplane junkyard

Chorus

I sing my Westerbork serenade

The silver moon shines along the railway track

On the heath

I sing my Westerbork serenade

With a pretty lady, walking together cheek to cheek

And my heart burns like the boiler in the boiler house

I never hit me quite like this at Mother’s place

I sing my Westerbork serenade

Between the barracks, I threw my arms around her

Over there

This Westerbork love affair.

And so I went over to the medic,

The guy said there’s nothing you can do about it

But you feel a lot better

After giving the very first kiss (and you shouldn’t)

Chorus repeats

A fellow artist who met them at the time wondered how Jews were allowed to walk freely in Amsterdam, without a yellow star. They told him about their temporary freedom. He suggested that they go into hiding but they refused. It was a camp rule, “Those who escaped risked the lives of their families,” who would face deportation. So they returned.

In September 1944, they were deported with their wives to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. They did not stay long. On a transport from the ghetto, the duo were separated from their wives. Salomon and Arnold were deported from camp to camp: Auschwitz, Sachsenhausen, Ohrdruf, Buchenwald and finally, after a 10-day train journey, they wound up in Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp, where they died of exhaustion shortly before its liberation. Nol van Wesel died on 20 March 1945 at the age of 26 and Max Kannewasser died on 15 April 1945 at the age of 28.

Salomon’s mother-in-law, Marie Louise Koster, recalled seeing their bodies dragged out of the sick barracks onto a van, to be cremated. She was in the so-called Stern Lager (Star Camp) with her husband Willem and her daughter Sonja. Salomon’s wife Suzanne survived Mauthausen and Auschwitz and lived in the United States until 2018. Gerda was killed in Auschwitz in 1944. Neither had children. Arnold’s parents were killed in Auschwitz in 1942. Salomon’s parents had died before the war. Their cousin Barend Beek went via Westerbork to Auschwitz and was killed in a subcamp of Stutthof on 11 December 1944.

They may have been murdered—but their music lives on.

sources

https://holocaustmusic.ort.org/places/camps/western-europe/westerbork/johnny-jones/

You must be logged in to post a comment.