The Frankfurt Auschwitz trial (1963–1965) was one of the most significant post-war trials of Nazi war criminals in West Germany. It prosecuted former SS officers and personnel involved in the operation of the Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp during the Holocaust. The trial, held in Frankfurt am Main, was led by Fritz Bauer, a German-Jewish prosecutor determined to bring Nazi criminals to justice.

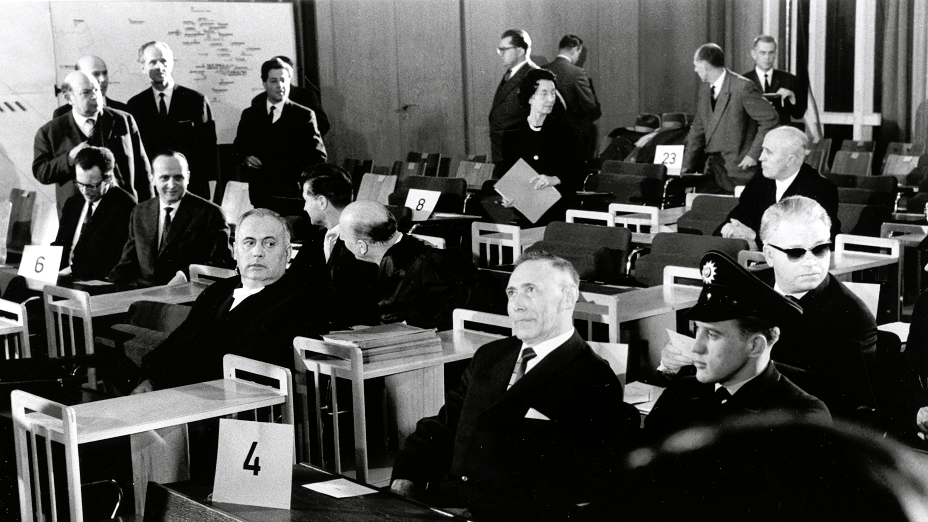

Unlike the Nuremberg Trials, which were conducted by the Allies, this was a West German national trial and marked a shift in Germany’s willingness to confront its Nazi past. A total of 22 defendants were charged, mostly mid- and lower-ranking officials, accused of murder and aiding mass murder. The trial was notable for extensive eyewitness testimonies from Holocaust survivors, which provided harrowing details of the atrocities committed at Auschwitz.

In 1965, the court convicted 17 defendants, sentencing them to prison terms ranging from a few years to life, while six were acquitted. The trial played a crucial role in educating the German public about Nazi crimes and is considered a milestone in confronting Holocaust history.

The first Auschwitz Trial in Frankfurt commenced at the Römer, Frankfurt’s City Hall, on December 20, 1963.

Approximately 360 witnesses were called to testify, including around 210 survivors. Below are testimonies from some of the witnesses.

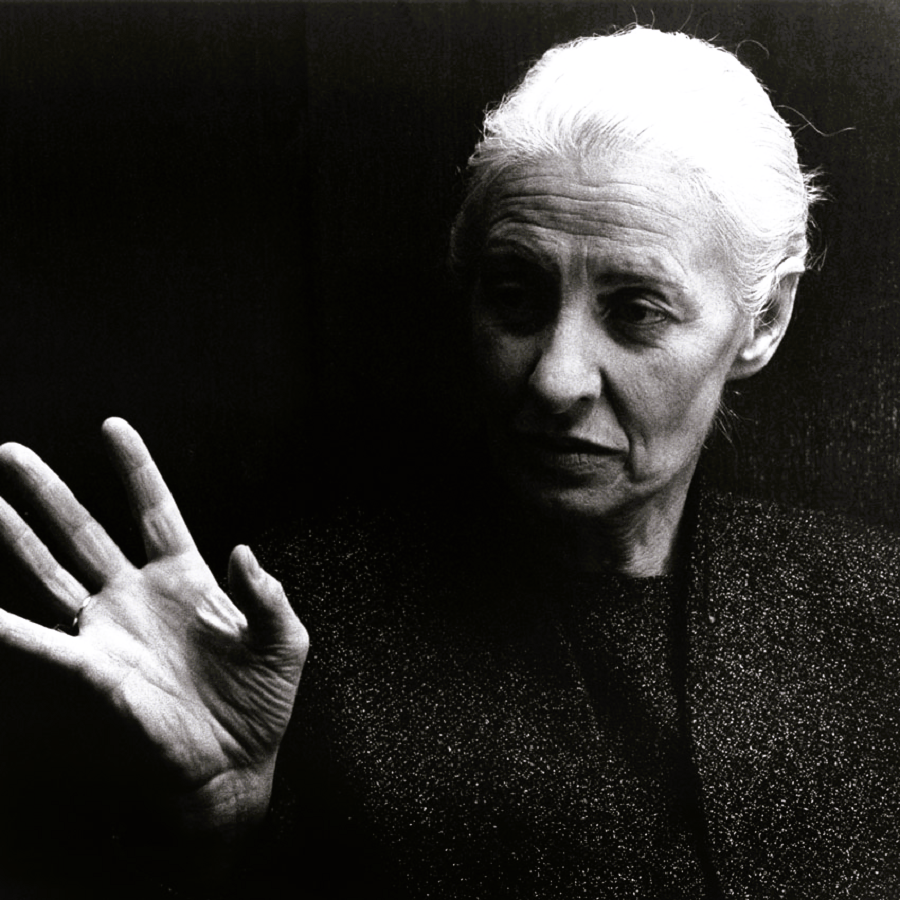

Ella Lingens (née Reiner), born in Vienna in 1908, was arrested by the Gestapo in October 1942 for “favoring Jews.” After spending four months in police custody, she was deported to Auschwitz. Lingens had attempted to help Polish Jews escape to Switzerland. As a “Reich German” and political prisoner, she was assigned the number 36,088.

A medical doctor by profession, Lingens worked primarily as a prisoner doctor in the infirmary of the women’s concentration camp in Birkenau (camp section BIa). In early December 1944, she was transferred to the Dachau concentration camp near Munich, where she was liberated by the American army at the end of April 1945.

But I know that all the SS doctors had their own personal ambitions and somehow felt that they wanted to gain something from their time in service, and everyone came up with something. For example, Dr. König wanted to conduct experiments on the question of erythrocyte sedimentation rates. And Mengele conducted his experiments, some of which were these ethnological descriptions, the twin stories. […] And whether the people, these SS doctors, asked whether they were allowed to do this or not, I don’t know. I assume not, because everyone there could do whatever they wanted.

(22nd day of the trial, March 2, 1964)

Mariana Adam (née Willner), born in 1923 in Tîrgu Mureș/Neumarkt (Romania), was deported to Auschwitz in June 1944 along with her parents from Rákosliget (now a district of Budapest). Upon arrival, she was held unregistered for several days as a so-called “depot prisoner” in the “Mexico” (BIII) transit camp.

She was then transported to the Plaszów concentration camp near Kraków. After the dissolution of Plaszów, Adam was sent back to Auschwitz in early August 1944 as part of a transport carrying 7,500 Jewish female prisoners. She was registered as prisoner number A-17,169.

At the Birkenau ramp, an SS officer selected Adam, and a few days later, she was told that he was Dr. Victor Capesius, the camp’s pharmacist. Along with other Jewish women, Adam was sent to camp section BIIb, which housed Jewish women from Hungary following the second liquidation of the Theresienstadt family camp in July 1944.

We were crammed into wagons under impossible conditions: 130, 140 people in a cattle wagon, with no food, no water, almost no air. If we lifted a foot, we couldn’t put it down. Some of us went mad. Others died. But they were standing next to us, they couldn’t fall down. It was a hellish journey.

(112th day of the trial, November 16, 1964)

Jehuda Bacon, born in 1929 in Moravská Ostrava (Czechoslovakia), was deported from his hometown in the autumn of 1942 to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, which the Nazis referred to as the “old people’s ghetto.” In December 1943, he was transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and placed in the Theresienstadt family camp (BIIb), where he was assigned prisoner number 168,194.

During the so-called second liquidation of the family camp, Bacon and 70 other boys were transferred to the “children’s block” of the men’s camp (BIId). He was forced to work in a commando that pulled a so-called trolley and, as part of this labor, entered the fenced-off crematoria area, where he witnessed the gas chambers.

During the “evacuation” of Auschwitz on January 18, 1945, Bacon survived the death march and was transported to the Mauthausen concentration camp near Linz, Austria. He was later liberated by the American army at the Gunskirchen subcamp.

At the time of his testimony in October 1964, Jehuda Bacon was 35 years old and living in Jerusalem, Israel, where he worked as an artist and art teacher.

We were often in the “sauna,” and when there were no people in the gas chambers and we had finished our work, the Kapo allowed us to warm ourselves in the gas chambers, so that I saw the gas chambers very closely and also the undressing chambers. And through this work we saw much more than the prisoners [normally] could see.

(106th day of the trial, October 30, 1964)

(When the witness Jehuda Bacon refers to the term “sauna,” he does not mean the building in the Birkenau extermination camp that was in use in December 1943 and referred to as “sauna” in camp language—a facility where prisoners’ clothing was disinfected and where washrooms were available for camp inmates. Instead, Bacon uses “sauna” to describe the crematoria with gas chambers. This was part of the SS’s deception, as they misled arriving victims by telling them they were going to the “bath” or “sauna” to wash and change before their execution.)

Ernst Toch, born in Vienna in 1912, was arrested by the Gestapo in mid-1939 and deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin. In October 1942, following an order from Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler to transfer Jewish prisoners from concentration camps in the Reich to Auschwitz, Toch was among more than 400 prisoners sent there. He was registered as prisoner number 70,231.

Initially subjected to brutal forced labor in the Chelmek subcamp, Toch later became a prisoner clerk in the infirmary of Block 21. In the autumn of 1944, he was transferred to the clothing store in Block 28, where he managed the laundry store. Unlike many others, Toch managed to avoid the death march, which led to the deaths of countless prisoners. He remained in Auschwitz and was liberated by the Red Army on January 27, 1945.

A part of this corridor was covered with blankets at the end. A number of prisoners stood in front of these blankets, undressed. And since no one else was to be seen there, I went behind the blanket compartment and there I could see that a prisoner who had just been called in had to sit on a stool. He was asked to put his left hand over his eyes, he was asked where he came from – it was in the wrong order: first he was asked where he came from, and then he was asked to put his left hand over his eyes, and then the Klehr injected. […] In the chest.

(52nd day of the trial, June 5, 1964)

(Klehr administered lethal injections of phenol (carbolic acid) to prisoners using a so-called record syringe—a long hollow needle attached to a large glass cylinder with a metal piston. The injections were typically fatal within moments.)

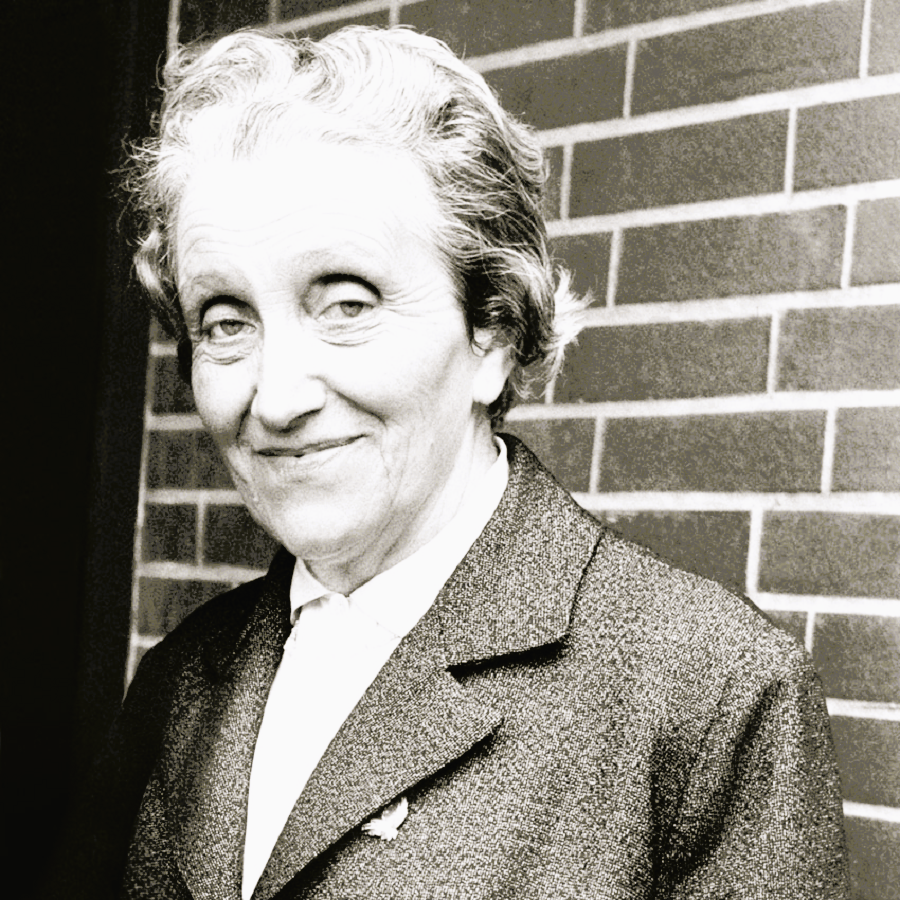

Gisella Böhm, born in 1897 in Sighișoara/Schäßburg, Romania, was taken with her family in April 1944 as part of the “Hungary Action” to a makeshift ghetto in Tîrgu Mureș. This ghetto, located near their home in Odorhei/Oderhellen, served as a collection point before deportation to Auschwitz.

At the end of May 1944, Böhm was transported to Auschwitz alongside her daughter Ella, who also later testified as a witness in the Auschwitz trial. Her husband was deported separately on a death train. Upon arrival, Böhm was subjected to a selection process conducted by an SS commission that included the defendant Dr. Victor Capesius and SS doctors Dr. Josef Mengele and Dr. Fritz Klein. She was assigned to the camp and registered as prisoner number A-25,382.

We were arranged in rows, the women walking to the right, we were led into a bath and completely depilated. We were then shaved. All hairy parts of our skin were stripped of hair, with razors and completely unevenly. They were very disfigured figures, these shaved women, and very unhappy. I consoled them: “We are going to work, we will be disinfected, we will be given clothes.”

(113th day of the trial, November 19, 1964)

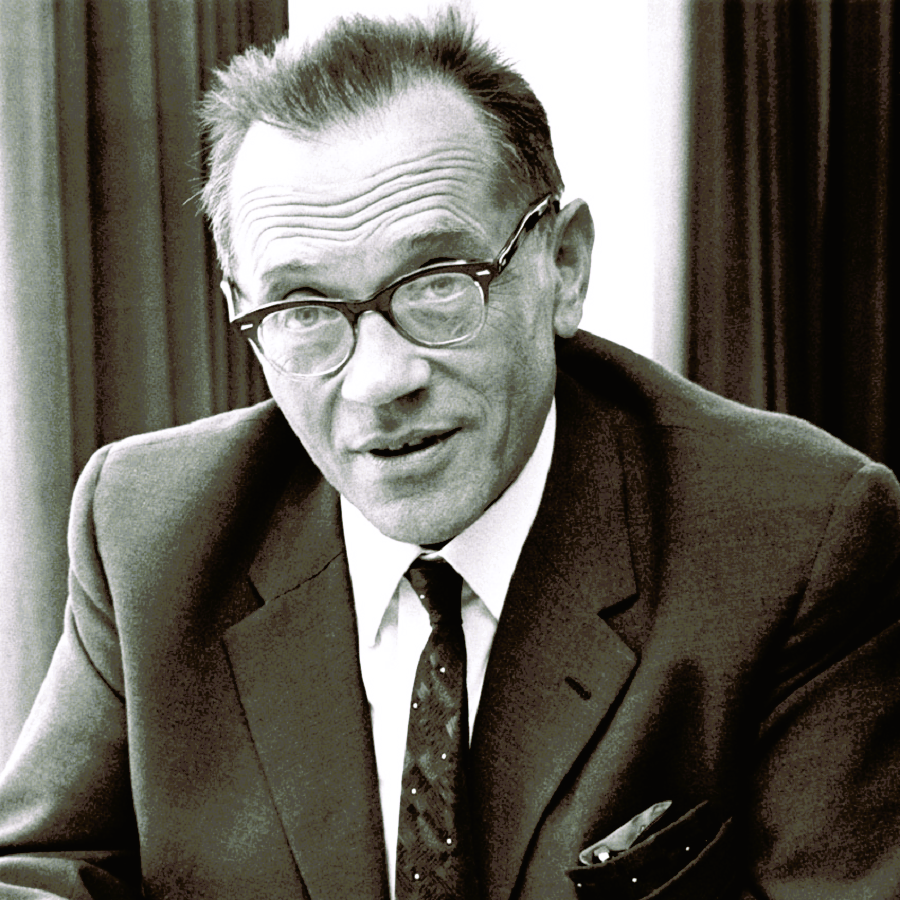

The trial garnered significant publicity in Germany but was ultimately considered a failure by Fritz Bauer. He criticized the media for portraying the accused as monstrous outliers, which allowed the German public to dissociate themselves from any moral responsibility for the atrocities committed at Auschwitz. This framing suggested that the genocide was the work of a few pathological individuals rather than a systemic crime carried out with the participation of ordinary Germans.

Bauer was also deeply troubled by the legal framework of the trial. Since those who followed orders in carrying out murders were legally treated as mere accomplices rather than principal perpetrators, it implied that the Nazi policies of genocide and the camp regulations at Auschwitz were, in some way, legally valid.

He lamented that the trial reinforced a “wishful fantasy that there were only a few people with responsibility … and the rest were merely terrorized, violated hangers-on, compelled to do things completely contrary to their true nature.”

Moreover, Bauer argued that the judges’ rulings created the false impression that Nazi Germany had been an occupied country where most Germans had no choice but to obey orders. He countered this by asserting,

“But this … had nothing to do with historical reality. There were virulent nationalists, imperialists, anti-Semites, and Jew-haters. Without them, Hitler was unthinkable.”

Public sentiment at the time reflected this reluctance to confront the past. A public opinion poll conducted after the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials found that 57% of Germans were opposed to holding further Nazi trials.

sources

http://www.wollheim-memorial.de/en/monowitz_fap_i_en

https://landesarchiv.hessen.de/mow/chapters/chapter-5_en

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankfurt_Auschwitz_trials

https://auschwitz-prozess-frankfurt.de/index.php/der-auschwitz-prozess/zeugen#zeugen

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment