The Holocaust remains one of the darkest periods in human history, and while the atrocities committed by the Nazi regime are well-documented, the role of major corporations in facilitating these crimes is often less discussed. One such corporation is International Business Machines (IBM), an American multinational known for its computing technology. The company’s involvement with Nazi Germany, particularly its provision of technology that enabled the efficient tracking and extermination of Jews and other persecuted groups, raises serious ethical and historical questions.

IBM’s Business with Nazi Germany

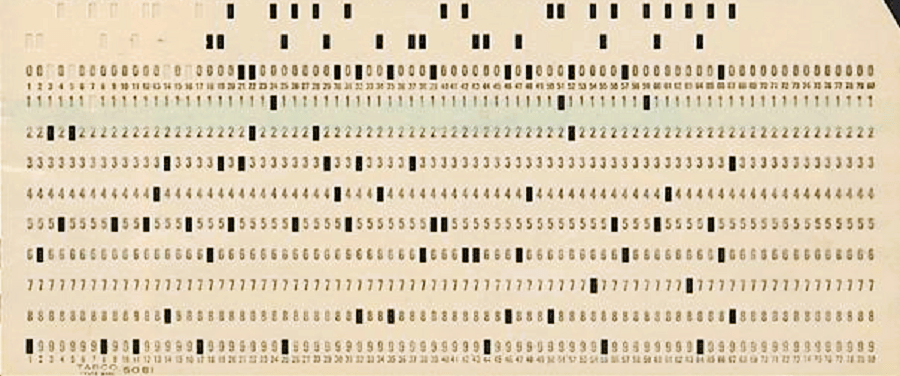

IBM, founded in 1911 as the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR) before being renamed in 1924, was already a significant player in data processing technology by the 1930s. During that time, it specialized in punch-card systems, a precursor to modern computing that allowed for the rapid organization, tabulation, and retrieval of vast amounts of data.

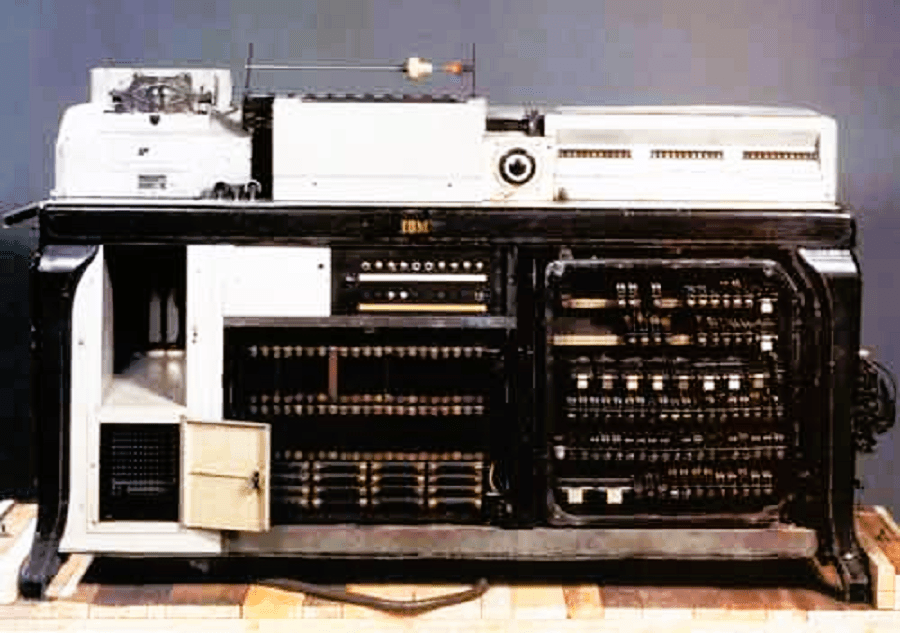

Under the leadership of Thomas J. Watson, IBM aggressively expanded internationally, including into Germany, where it operated through its subsidiary, Deutsche Hollerith Maschinen Gesellschaft (Dehomag). This subsidiary played a crucial role in supplying punch-card machines to the German government, which the Nazis used for various administrative functions, including census-taking, railroad scheduling, and population tracking.

The Role of IBM’s Technology in the Holocaust

The Nazis were notorious for their meticulous record-keeping, and their ability to identify and track individuals was central to the execution of the Holocaust. IBM’s punch-card technology was instrumental in organizing this mass persecution.

- Census and Identification: The Nazi regime conducted a detailed census to identify Jewish citizens and other targeted groups. IBM’s punch-card systems allowed for rapid categorization based on race, profession, and residence, making it easier to locate individuals for deportation.

- Transportation Logistics: IBM technology was used to manage Germany’s vast railway system, which transported millions of people to concentration camps such as Auschwitz and Treblinka. The efficiency of these transports directly contributed to the scale and speed of the genocide.

- Camp Administration: Concentration camps relied on IBM’s punch-card systems to catalog prisoners, monitor forced labor, and track execution schedules. Each prisoner was assigned a numerical code, processed through IBM systems, to keep records of their fate.

Did IBM Know?

One of the most controversial aspects of IBM’s involvement is the question of how much its executives, particularly Thomas J. Watson, knew about how their technology was being used. Evidence suggests that IBM was not just a passive supplier but an active business partner to Nazi Germany.

Watson was awarded a medal by Adolf Hitler in 1937, symbolizing IBM’s cooperation with the Nazi regime.

While he returned the medal in 1940 as international tensions rose, IBM’s business dealings with Germany continued even after the U.S. entered World War II. Through Dehomag and other subsidiaries, IBM maintained indirect control over its technology and operations in Nazi-occupied territories.

Aftermath and Ethical Lessons

After the war, IBM distanced itself from its wartime activities, and its role in the Holocaust was largely forgotten until researchers, particularly investigative journalist Edwin Black, uncovered extensive documentation in the early 2000s. In his book IBM and the Holocaust, Black detailed how IBM’s technology was integral to Nazi efficiency in persecution and genocide.

Despite the evidence, IBM has never formally taken responsibility or issued a public apology. The company maintains that it lost direct control over its German subsidiary after the U.S. entered the war, a claim disputed by historical records showing that IBM continued to profit from its operations in Nazi-controlled Europe.

Punch cards, also known as Hollerith cards after IBM founder Herman Hollerith, were the precursors to modern computers. These cards stored information using holes punched in specific rows and columns, which were then “read” by a tabulating machine—similar to how a player piano functions. Initially designed for census tracking, the Hollerith system was later adapted for various data-processing tasks.

From the onset of the Nazi regime in 1933, IBM leveraged its exclusive punch card technology and global monopoly on information processing to support Hitler’s anti-Jewish policies. Step by step, IBM facilitated the systematic persecution and extermination of Jews by providing punch cards, machinery, training, and servicing. The company directly managed operations through its New York headquarters and its European subsidiaries, including Deutsche Hollerith-Maschinen Gesellschaft (DEHOMAG) in Germany, as well as branches in Poland, the Netherlands, France, Switzerland, and other occupied countries.

Among the punch cards published were those used by the SS, including the SS Rassenamt (Race Office), which specialized in racial classification and coordinated with other Reich offices. Another punch card was custom-designed by IBM for Richard Korherr, a statistician who reported directly to Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler and collaborated with Adolf Eichmann—both key architects of the Holocaust. These punch cards, bearing the IBM subsidiary DEHOMAG’s insignia, illustrate how IBM’s technology was used by the Nazi regime.

In 1937, as Nazi persecution intensified, Hitler awarded IBM CEO Thomas Watson the Order of the German Eagle with Star, a medal created to honor foreign individuals who provided exceptional service to the Third Reich. Though Watson returned the medal in 1940 amid public outrage, newly uncovered documents reveal that IBM continued expanding its role in Nazi operations. A letter dated June 10, 1941, from IBM’s New York office confirms that IBM headquarters directly oversaw its Dutch subsidiary, which was used to identify and facilitate the extermination of Dutch Jews. Similar subsidiaries were established across Nazi-occupied Europe, often under the name “Watson Business Machines.”

IBM’s involvement extended to concentration camps, where it maintained a dedicated Hollerith Department to process prisoner data. Declassified IBM concentration camp codes reveal the company’s numerical designations: Auschwitz was coded as 001, Buchenwald as 002, and Dachau as 003. Prisoner categories were similarly reduced to numbers—3 for homosexuals, 9 for “anti-social” individuals, 12 for Romani people, and 8 for Jews. Methods of death were also coded: 3 indicated natural causes, 4 meant execution, 5 signified suicide, and 6 referred to “special treatment”—a euphemism for execution in gas chambers. IBM engineers designed these systems, printed the punch cards, configured the machines, trained personnel, and provided on-site maintenance every two weeks.

Recently released photographs show the Hollerith Bunker at Dachau, a fortified structure housing IBM machines and controlled by the SS.

Built to withstand Allied bombardment, the facility underscores the importance the Nazis placed on IBM technology—not just in their war against the Jews but also in military logistics and railway coordination. Watson personally approved expenses for bomb shelters to protect DEHOMAG facilities because IBM bore the costs, affecting its profit margins. His approval was necessary as he received a 1% commission on all Nazi business profits.

Two U.S. government memos highlight IBM’s complicity. A State Department memo dated December 3, 1941—just days before the attack on Pearl Harbor—documents IBM’s top attorney, Harrison Chauncey, expressing concerns that “his company may someday be blamed for cooperating with the Germans.” Another memo, from the Justice Department, emerged during a federal investigation into IBM’s dealings with the Nazis. Economic Warfare Section chief investigator Howard J. Carter concluded, “What Hitler has done to us through his economic warfare, one of our own American corporations has also done … IBM is in a class with the Nazis.” He further described IBM as “an international monster.”

Despite IBM’s modern reputation for technological innovation, its dark history cannot be overlooked. The Treaty on Genocide, Article 2, defines genocide as acts intended to destroy a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. Article 3 lists “complicity in genocide” as a punishable act, applying to “rulers, public officials, or private individuals.”

In 2001, a lawsuit was filed under the Alien Tort Claims Act against IBM for allegedly facilitating the Holocaust and covering up DEHOMAG’s activities. However, the suit was dropped to avoid delaying compensation payments from a German Holocaust fund for survivors. IBM’s German division contributed $3 million to the fund without admitting liability. In 2004, the human rights group Gypsy International Recognition and Compensation Action (GIRCA) sued IBM in Switzerland, but the case was dismissed in 2006 due to the statute of limitations.

Edwin Black’s book IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America’s Most Powerful Corporation explores IBM’s role in the Holocaust. Newly released in an expanded edition, it sheds further light on the corporation’s complicity in one of history’s darkest chapters.

The case of IBM and the Holocaust serves as a chilling reminder of how technology can be used for both progress and destruction. It also raises ethical questions about corporate responsibility in wartime and the extent to which companies should be held accountable for their complicity in crimes against humanity.

While IBM has since evolved into a leader in ethical AI and technology, its past involvement with Nazi Germany remains a stark example of the dangers of unchecked corporate power. This history underscores the importance of vigilance, ethical governance, and accountability in technological advancements, ensuring that such tools are never again used for oppressive or genocidal purposes.

Sources

https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=34689

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_J._Watson

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/ibm-and-nazi-germany/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/27058571

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/mar/29/humanities.highereducation

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/ibm-and-quot-death-s-calculator-quot-2

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IBM_and_the_Holocaust

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment