Tomorrow is St. Patrick’s Day, Ireland’s national holiday—a time to reflect on Ireland’s complex Holocaust history

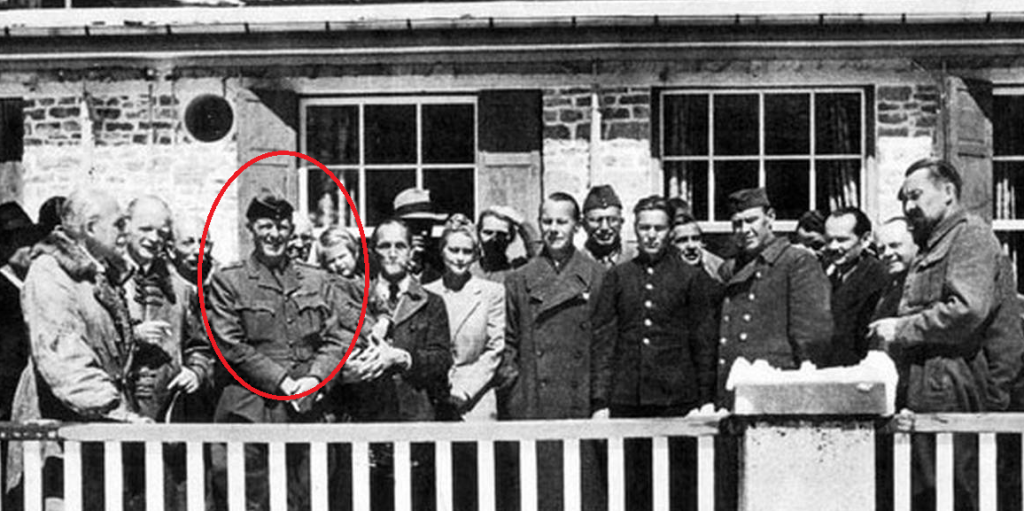

On May 2, 1945, Taoiseach(prime minister) Éamon de Valera expressed condolences to the German ambassador following the death of Adolf Hitler. This gesture was met with widespread national and international criticism. Angela D. Walsh, a resident of East 44th Street, New York, wrote to de Valera the following day, stating, “I am horrified, ashamed, humiliated… You, who are the head of a Catholic country, have now shown allegiance to a devil.”

This act also raised a significant theological question. De Valera was a devout Roman Catholic, and the Catholic Church has long regarded suicide as a grave offense constituting mortal sin. As stated in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, “It is God who remains the sovereign master of life. … We are stewards, not owners, of the life God has entrusted to us. It is not ours to dispose of.” Beyond Hitler’s undeniable responsibility for genocide, his suicide also violated a core Catholic teaching. Why, then, would de Valera offer condolences to someone who had committed both heinous crimes and a mortal sin? If Hitler had been an Irish Catholic, he would not have received absolution.

The rationale behind de Valera’s decision lay in Ireland’s policy of neutrality. His expression of condolences was in accordance with diplomatic protocol. Furthermore, historian Paul Bew suggests that de Valera dismissed reports of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp as “anti-national propaganda,” not out of disbelief but because acknowledging the Holocaust would have undermined the core justification for Irish neutrality.

However, as Ireland’s leader, de Valera should have been acutely aware that several Irish citizens were murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

Irish Holocaust Victims

Ettie Steinberg

Ettie (Esther) Steinberg was born in Veretski (Vericky), Czechoslovakia, on January 11, 1914. She was one of seven children. In 1925, her family moved to Ireland and settled on Raymond Terrace off the South Circular Road in Dublin. Ettie attended St. Catherine’s School on Donore Avenue before working as a seamstress.

In 1937, she married Wojteck Gluck, a Belgian goldsmith, in Greenville Hall Synagogue, Dublin. The couple relocated to Antwerp and later to Paris, where their son, Leon, was born on March 28, 1939.

By 1942, the family had moved to Toulouse, where they were arrested and detained at the Drancy Transit Camp near Paris. Ettie’s relatives in Dublin managed to secure visas for the Glucks to travel to Northern Ireland, but tragically, the documents arrived too late. Ettie, Wojteck, and Leon were rounded up and deported.

On September 2, 1942, the Glucks were transported by train from Drancy to Auschwitz, where they were murdered in gas chambers two days later.

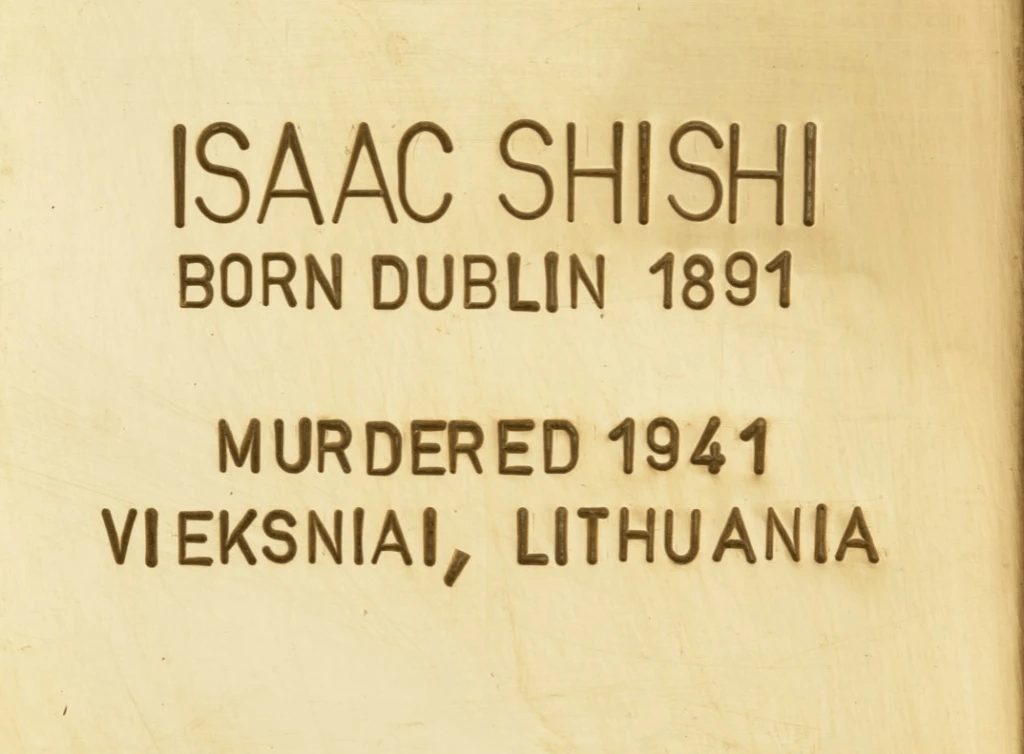

Isaac Shishi

Isaac Shishi was born in Dublin on January 29, 1891, to a Lithuanian Jewish family who had emigrated to Ireland in 1890. His sister, Rose (or Rachel), was born in Dublin in 1892. The family lived on St. Alban’s Road, off the South Circular Road.

In 1893, Isaac’s parents returned to Lithuania, where they had three more children. Isaac remained in Lithuania, married Chana Garbel in 1922, and had a daughter, Sheine, in 1924.

In 1941, Isaac, Chana, and Sheine were murdered by the Nazis in Vieksniai, Lithuania, despite Isaac being an Irish citizen.

Ephraim and Jeanne (Lena) Saks

The parents of Ephraim and Lena Saks made their way from Ponedel in Lithuania to Dublin in 1914 via Leeds and Antwerp. They had three young children when they arrived, and the family remained in Ireland for the First World War duration. Children, Ephraim was born in Dublin on 19 April 1915, and his sister, Lena (aka Jeanne), was born on 2 February 1918.

Sometime after the end of the First World War, the family returned to Antwerp. A Belgian record shows the family was living together with the five children.

Ephraim was a furrier (Furrier is defined: as a person who either makes clothing out of fur, repairs fur garments or sells them) and single, living in France at the outbreak of the Second World War. He was arrested and deported from the Drancy Transit Camp in Paris to Auschwitz on 24 August 1942. There he was murdered by the Nazis.

Jeanne (aka Janie, aka Lena) was single and professionally a salesperson, living in Antwerp during the war. She was captured and deported to Auschwitz. She was murdered there by the Nazis at the camp in 1942/43. Testimony by Julia Apfel, a sister of Ephraim and Jeanne Saks, is on the Yad Vashem website. Three of Julia’s siblings, two of whom, Ephraim and Jeanne (Lena) were born in Dublin and hence were Irish citizens, were murdered in the Holocaust.

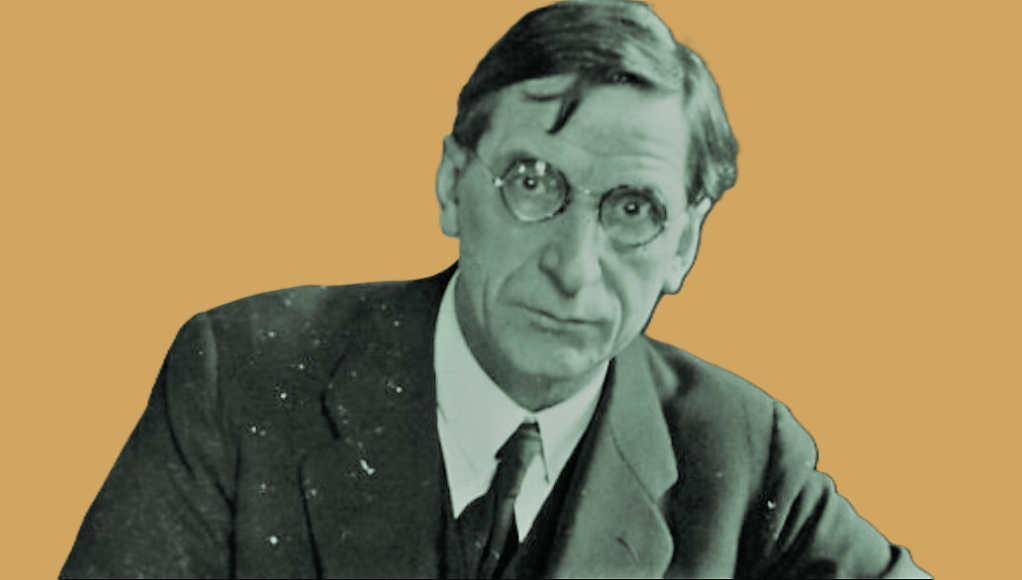

Major John McGrath

John McGrath, a native of County Roscommon, left his position as manager of the Theatre Royal in Dublin at the outbreak of World War II to join the war effort. A World War I veteran, he remained a reserve officer. Captured in northern France after Dunkirk in June 1940, he became the senior British officer in a camp for Irish-born POWs whom the Germans sought to recruit.

McGrath was later imprisoned in Sachsenhausen and, in 1943, transferred to Dachau. Classified as a “Nacht und Nebel” (Night and Fog) prisoner, he was meant to disappear without a trace. He endured nearly two years in the camps before being liberated in April 1945.

After his release, McGrath returned to Dublin, but his time in captivity took a severe toll. Suffering from nervous and intestinal disorders, he resigned from the Theatre Royal and passed away on November 27, 1946. His death, resulting from his internment, arguably makes him a Holocaust victim.

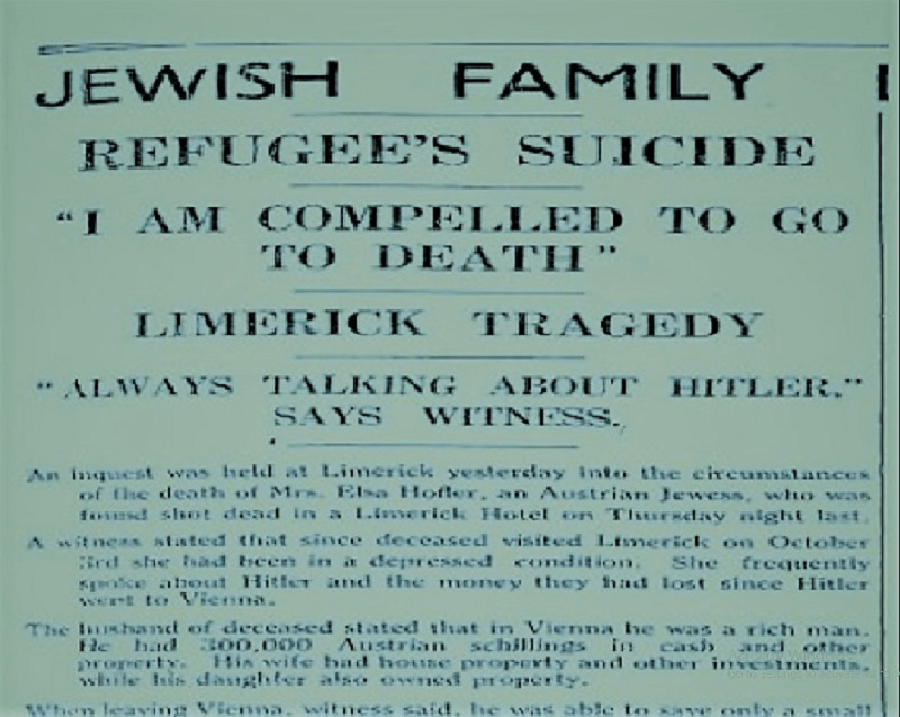

Elsa Reininger

Elsa Reininger was not an Irish citizen. However, there is a direct link between her death and Ireland.

Elsa had fled Austria and arrived in Limerick from England in October 1938. There her passport was stamped for a 48 hours stay, basically a short-term visa.

The experiences she witnessed in Austria disturbed Elsa. She had shattered nerves from what she had seen and experienced in Vienna and the possibility that she might have to return there. She was suffering from depression. On 27 October 1938, she booked a room at the Crescent Hotel. There she took a gun from her handbag, and as she lay on the bed, she put it to her head and pulled the trigger, killing herself at age 57. No one heard the shot. She was right to be concerned because she knew the authorities would deport her back to Austria.

De Valera’s diplomatic protocol may have been intended to maintain Irish neutrality, but his condolences to the German ambassador cannot be separated from the reality that Irish citizens and those with connections to Ireland were among Hitler’s victims. The stories of Ettie Steinberg, Isaac Shishi, Ephraim and Jeanne Saks, Major John McGrath, and Elsa Reininger highlight the devastating impact of the Holocaust on Ireland and its people.

Sources:

https://www.holocausteducationireland.org/ireland-and-the-holocaust

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment