This blog is not intended to pass judgment. However, when writing about the Holocaust, it’s important not to shy away from its more controversial aspects. As I mentioned at the beginning, my goal is not to judge anyone—because the truth is, I cannot say with certainty how I would have acted in a similar situation.

Chaim Mordechai Rumkowski remains one of the most controversial figures of the Holocaust due to his role as the head of the Jewish Council (Judenrat) in the Łódź Ghetto. Appointed by the Nazis in 1940, Rumkowski wielded immense power over the ghetto’s population, making life-and-death decisions that have been debated by historians and scholars. His policies and leadership strategy, often characterized by his belief in survival through labor, continue to evoke strong reactions, ranging from accusations of collaboration to arguments that he was attempting to save as many lives as possible in an impossible situation.

Background and Rise to Power

Before the war, Chaim Rumkowski was a businessman and a Zionist activist involved in orphan care in Łódź. When the Germans occupied Poland in 1939, they quickly established ghettos to segregate the Jewish population. The Łódź Ghetto, the second-largest in Nazi-occupied Europe, was officially sealed in 1940, trapping approximately 160,000 Jews within its confines. The Nazis appointed Rumkowski as the head of the Judenrat, a governing body responsible for maintaining order, implementing German policies, and distributing scarce resources.

Rumkowski’s Leadership and Policies

Rumkowski’s leadership was defined by his belief that making the ghetto economically indispensable to the Nazis could ensure its survival. Under his administration, the Łódź Ghetto became an extensive forced labor camp, producing goods for the German war effort. Factories were established, and residents, including children and the elderly, were forced into grueling labor under the pretext that productivity would protect them from deportation.

Rumkowski saw himself as a paternal figure, often referring to the ghetto’s inhabitants as “his children.” His speeches, particularly the infamous “Give Me Your Children” speech in 1942, remain among the most chilling moments of Holocaust history.

In this speech, he urged parents to surrender their children for deportation, arguing that compliance with Nazi demands would save the remaining population. This decision, which led to the deportation and subsequent murder of thousands of children and elderly individuals, has been a focal point of his moral and historical assessment.

Controversy and Debate

The nature of Rumkowski’s leadership remains deeply contentious. Some view him as a power-hungry figure who enjoyed his privileged status, indulging in personal luxuries while the ghetto’s inhabitants starved. His authoritarian rule, the establishment of a personal police force, and the elimination of political rivals painted him as a self-serving despot. Moreover, his willingness to cooperate with the Nazis, including organizing deportations, led many to label him a traitor.

Conversely, others argue that Rumkowski was operating under extraordinary duress and made difficult choices in a desperate attempt to minimize Jewish casualties. Unlike other ghettos that experienced violent resistance, Łódź survived longer than most, only being liquidated in 1944. Some historians suggest that this extended existence, facilitated by his labor policies, gave certain individuals a greater chance of survival, though ultimately, the vast majority of the ghetto’s population perished in concentration camps.

he Germans authorized Chaim Rumkowski as the sole authority in managing and organizing life within the Łódź Ghetto. His power stemmed not only from this official designation but also from his domineering personality and forceful leadership style. Initially, Hans Biebow, the Nazi administrator of the ghetto, granted Rumkowski significant control—so long as it did not interfere with key German objectives: maintaining absolute order, confiscating Jewish property and assets, enforcing coerced labor, and serving Biebow’s own personal interests.

Their relationship functioned efficiently—at least on the surface. Rumkowski was given the freedom to govern the ghetto as he saw fit, while Biebow reaped the benefits. In an effort to maintain this dynamic, Rumkowski obeyed every order with little resistance, even offering gifts and personal favors to Biebow. His willingness to cooperate with the Nazis was summed up in a speech where he reportedly boasted, “My motto is always to be at least ten minutes ahead of every German demand.” He believed that by anticipating their expectations, he could satisfy them and, in turn, safeguard the Jewish population.

Despite these efforts, Łódź was the last ghetto in Eastern Europe to be liquidated. When the city was liberated, only 877 inhabitants survived—hiding with Polish rescuers. Rumkowski, however, played no role in their survival.

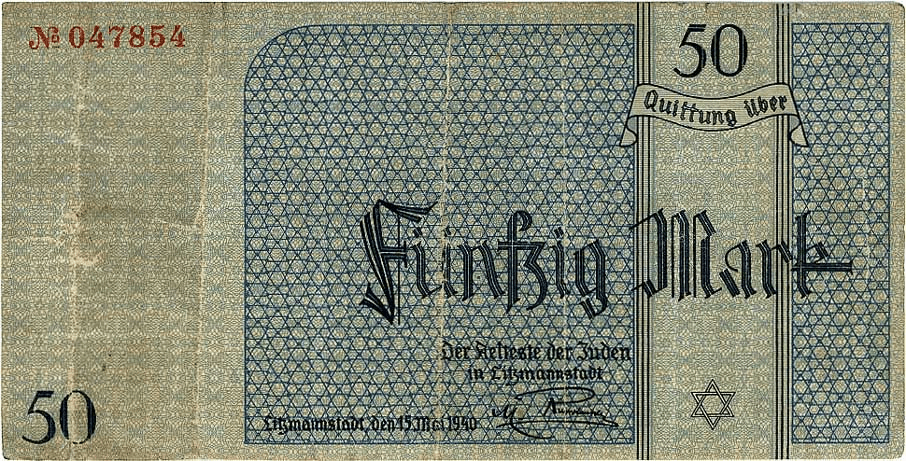

The Ghetto Currency and Economic Control

Following the confiscation of cash and valuables, Rumkowski proposed a new form of currency exclusive to the ghetto—the ersatz. This system allowed people to purchase food rations and basic necessities but was widely seen as an example of his growing hunger for control. As a result, residents mockingly referred to the currency as the “Rumkin.”

The ersatz currency had significant consequences. It discouraged smugglers, who could no longer be paid in real money, from risking their lives to bring in goods from the outside. Rumkowski defended this policy, arguing that food smuggling would “destabilize the ghetto with regard to the prices of basic commodities.” In effect, however, it further restricted the already desperate population.

Suppression of Dissent

Rumkowski tolerated no opposition. With the assistance of the Jewish police, he forcefully suppressed demonstrations and public protests. On occasion, he even called upon the Nazis to intervene, often leading to the execution of demonstrators. Those who led protests faced harsh repercussions: some were denied the right to work—an effective death sentence by starvation—while others were arrested, imprisoned, or deported to labor camps. By the spring of 1941, nearly all resistance to Rumkowski had been eliminated.

Forced Labor and the Path to Extermination

In the early stages of the Nazi occupation, German authorities had not yet finalized their plans for the ghetto. Initially, they intended to liquidate it by October 1940, but as the Final Solution was still in development, this plan was postponed. In the meantime, the Nazis began to take Rumkowski’s labor agenda seriously. Forced labor became a defining feature of ghetto life, with Rumkowski leading the charge. “In another three years,” he claimed, “the ghetto will be working like a clock.” His confidence, however, was not shared by Nazi officials. Max Horn of Ostindustrie dismissed the ghetto’s economic system as poorly managed, unprofitable, and focused on the wrong products.

By January 1942, mass deportations had begun. Rumkowski’s Judenrat was tasked with selecting individuals for transport to Chełmno extermination camp. Within weeks, 10,000 Jews were deported, followed by 34,000 more by April 2, 11,000 by May 15, and over 15,000 by mid-September—totaling approximately 55,000 victims. Those deemed “unfit for work”—including children and the elderly—were among the first to be sent to their deaths.

The Fate of Rumkowski

As the Łódź Ghetto was liquidated in August 1944, Rumkowski and his family were deported to Auschwitz, where they were reportedly killed by fellow Jewish prisoners who blamed him for their suffering. His death marked the end of one of the most controversial Judenrat leaders, but the debate over his legacy continues.

Chaim Rumkowski’s tenure as the head of the Łódź Ghetto Judenrat remains one of the Holocaust’s most complex moral dilemmas. Whether seen as a pragmatic leader trying to save his people or as a collaborator who facilitated their destruction, his actions force us to grapple with the agonizing choices imposed upon Jews under Nazi rule. His story serves as a reminder of the harrowing ethical and existential dilemmas faced by those caught in the machinery of genocide.

sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chaim_Rumkowski

https://historum.com/t/lodz-ghetto-leader-or-sell-out.54973/

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/give-me-your-children-voices-from-the-lodz-ghetto

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/chaim-mordechai-rumkowski

https://www.timesofisrael.com/king-chaim-ruler-of-the-lodz-ghetto-exposed-in-boston-exhibit/

https://www.yadvashem.org/holocaust/this-month/june/1940-2.html

https://academic.oup.com/hgs/article/35/2/185/6330495

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment