On the night of August 31, 1939, a German radio station in the small town of Gleiwitz (now Gliwice, Poland) became the stage for one of the most infamous false-flag operations in modern history. Known as the Gleiwitz incident, this orchestrated event was part of a broader Nazi propaganda effort to fabricate a justification for Germany’s planned invasion of Poland. In the following days, Adolf Hitler declared that Poland had attacked Germany, using Gleiwitz and other staged border clashes as proof of Polish aggression. The invasion that followed on September 1, 1939 marked the beginning of World War II.

This blog explores the Gleiwitz incident in depth, analyzing its planning, execution, and political function. It situates the event within the broader framework of Nazi strategy, propaganda, and international diplomacy, while reflecting on its enduring significance in the study of war, deception, and manufactured consent.

Historical Context: Tension on the German-Polish Border

By 1939, Hitler’s ambitions for Lebensraum—“living space” in Eastern Europe—were clear. Having already annexed Austria (1938) and dismantled Czechoslovakia (1938–1939), the Nazi regime turned its sights on Poland. Poland was strategically significant, rich in agricultural resources, and home to territory Germany had lost under the Treaty of Versailles after World War I.

Hitler, however, faced a challenge: he needed to present Germany as the victim of aggression rather than the instigator of conflict. Europe still bore the scars of World War I, and both domestic and international opinion were wary of war. Nazi propaganda, therefore, sought to frame Poland as the aggressor. This required a staged provocation that would legitimize German military action.

Planning the Operation: Himmler and Heydrich

The Gleiwitz incident was part of a larger operation codenamed “Operation Himmler”, overseen by Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, and executed by Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA).

Operation Himmler consisted of multiple false-flag operations designed to simulate Polish attacks on German territory. These staged incidents included sabotage, border skirmishes, and acts of violence, all designed to provide “evidence” of Polish hostility.

The Gleiwitz radio station attack was chosen as the most prominent of these provocations. Radio was a powerful medium in the 1930s, and the Nazis understood that a broadcast from a German station allegedly seized by Polish forces would have strong propaganda value.

The Execution: August 31, 1939

On the evening of August 31, SS operatives disguised as Polish soldiers stormed the Gleiwitz radio station. They briefly seized control and broadcast an anti-German message in Polish, urging ethnic Poles in Upper Silesia to resist German rule.

To bolster the appearance of authenticity, the SS used a “false flag” tactic involving the use of corpses. Prisoners from concentration camps—referred to as “Konserve” (canned goods) by the SS—were dressed in Polish uniforms, killed (often by lethal injection or gunfire), and left at the scene as supposed evidence of Polish attackers killed in the assault.

The most famous victim was Franciszek Honiok, a Silesian farmer with Polish sympathies who had previously been in German custody. He was executed and left behind as a “Polish saboteur,” his death carefully staged to lend credibility to the incident.

Propaganda and Hitler’s Declaration of War

The Gleiwitz incident was quickly broadcast as news of Polish aggression. On September 1, 1939, Hitler addressed the Reichstag, declaring:

“This night for the first time Polish regular soldiers fired on our own territory. Since 5:45 a.m. we are shooting back.”

In reality, German troops had already launched a massive invasion of Poland earlier that morning, coordinated with overwhelming force. The Gleiwitz incident, along with other Operation Himmler provocations, was thus not a cause of the invasion but rather its pretext—a carefully scripted narrative meant to reassure the German public and mislead foreign powers.

International Reception: Skepticism and Ineffectiveness

Despite the Nazi regime’s efforts, the Gleiwitz incident failed to convince much of the international community. Britain and France were not persuaded by German claims of Polish aggression. Just two days later, on September 3, 1939, both nations declared war on Germany, honoring their treaty obligations to Poland.

The incident did, however, succeed domestically. German citizens, bombarded by state-controlled media, largely accepted the narrative of Polish hostility. The propaganda created a climate of fear and patriotic fervor that made the invasion appear defensive rather than aggressive.

Historical Significance and Legacy

The Gleiwitz incident remains a paradigmatic example of a false-flag operation, where one party fabricates an attack by another to justify retaliatory action. Its significance lies not only in its immediate role in the outbreak of World War II but also in what it reveals about the mechanisms of propaganda and manipulation.

Scholars have since studied Gleiwitz as a case study in:

State-sponsored deception: Demonstrating how authoritarian regimes can manufacture events to legitimize violence.

The role of media in war: Highlighting how control of communication channels can shape public perception.

The fragility of evidence in propaganda wars: Showing how truth can be distorted or fabricated in the service of power.

The incident also raises ethical and political questions that remain relevant today. In an age of digital media, disinformation campaigns, and hybrid warfare, the Gleiwitz incident serves as an early warning of the dangers posed by manufactured narratives.

The Gleiwitz incident of August 31, 1939, was a small but pivotal moment in world history. By staging a false Polish attack, the Nazi regime created a pretext for the invasion of Poland, sparking a global conflict that would last six years and claim millions of lives. While the ruse was transparent to many outside observers, it was effective enough to rally domestic support and obscure the reality of Nazi aggression.

As an example of how propaganda and deception can be weaponized to justify war, Gleiwitz stands as both a historical warning and a contemporary reminder: the stories states tell about war are rarely straightforward, and critical scrutiny of official narratives is always necessary.

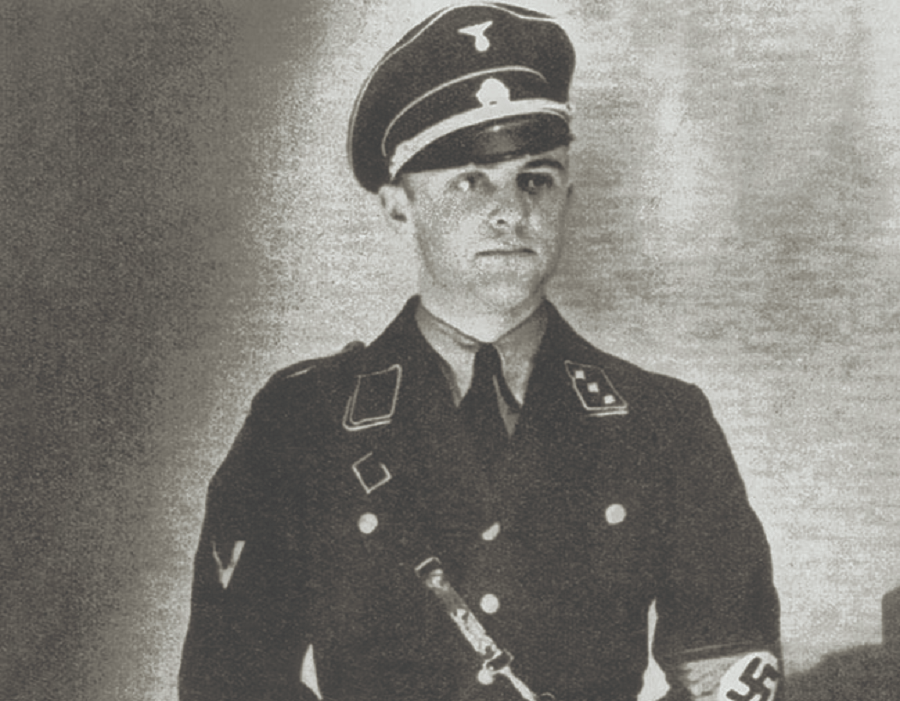

On the afternoon of August 31, 1939, in the German border town of Gleiwitz, SS-Sturmbannführer Alfred Naujocks sat anxiously in a hotel room with seven SS men. Two days earlier, the group had arrived under the guise of mining engineers to scout their objective. Now they waited for the signal to act. Their mission was simple but momentous: to stage a fake Polish attack that would provide Hitler with the pretext he needed to invade. Within hours, their deception would help ignite the most devastating conflict in human history—World War II.

Naujocks, a 27-year-old from Kiel on Germany’s Baltic coast, was an early devotee of Nazism. He joined the SS in 1931 after a brief stint at university, where he gained a reputation for street brawling—one fight with a Communist wielding an iron bar left his nose permanently flattened. A contemporary later described him as an “intellectual gangster,” a fitting label for a man who advanced rapidly through the SS under the patronage of Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the German police and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the SS intelligence service. In that role, Naujocks proved himself both ruthless and resourceful: he personally assassinated a dissident Nazi in Prague in 1935 and later helped establish the infamous Berlin brothel Salon Kitty. Ostensibly a playground for visiting dignitaries, the establishment doubled as an SS intelligence operation—its rooms wired for surveillance, its madam an undercover agent, and its clients ripe for blackmail.

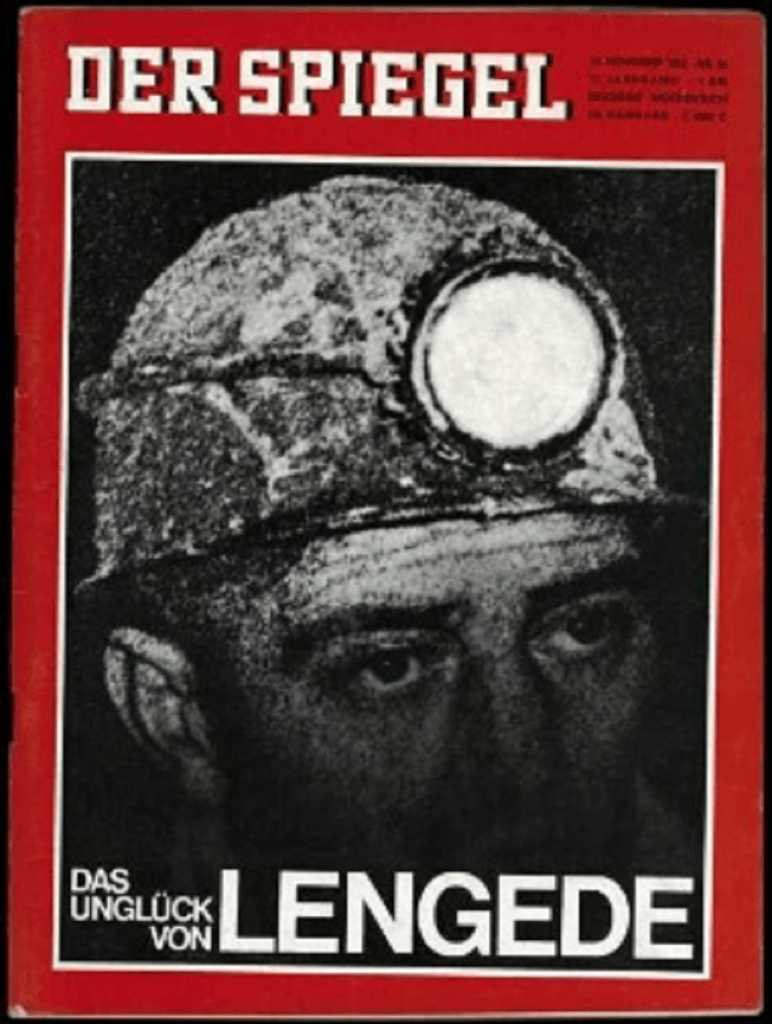

On November 12, 1963, he gave an interview to Der Spiegel. What follows is the English translation.

Interview with Alfred Naujocks (Der Spiegel, November 12, 1963)

SPIEGEL: Mr. Naujocks, on August 31, 1939—the eve of the war—the Gliwice radio station’s programming was interrupted shortly after 8 p.m. Polish voices rang out: “The Gliwice radio station is in our hands.”

NAUJOCKS: They were not Poles, but Germans.

SPIEGEL: You were the head of the SS commando that staged the attack.

NAUJOCKS: Yes. At the time, I was a Sturmbannführer and worked exclusively in the foreign intelligence service of the Reich Security Main Office. Gleiwitz was completely outside my area of responsibility. In that respect, it was a purely special assignment.

SPIEGEL: Who gave you that assignment?

NAUJOCKS: Heydrich, the head of the Reich Security Main Office. I was summoned to him at the beginning of August 1939. He explained that the partition of Poland between Russia and Germany was already decided, and that, for political reasons, the blame for what was to come had to be shifted—both abroad and within Germany. I was to carry out a special assignment, treated as a secret Reich matter: to occupy the transmitter at a specific time and day, upon receiving the release order, and ensure that a fiery speech in Polish was broadcast over the radio.

SPIEGEL: The “release order”?

NAUJOCKS: “Grandmother died” was the keyword that triggered the action.

SPIEGEL: Was the course of the action precisely defined?

NAUJOCKS: Heydrich set the framework:

I was not to contact any German authorities in Gleiwitz.

None of us was to carry identification showing SS, SD, police, or German Reich citizenship.

The operation had to appear real enough that German authorities would react as if it were genuine. At the same time, Heydrich wanted to test how quickly the security forces would respond.

SPIEGEL: Was there mention of leaving behind a dead “Polish insurgent” as evidence?

NAUJOCKS: No, not at that stage.

SPIEGEL: Who came up with that?

NAUJOCKS: I had nothing to do with it, and I don’t know who first proposed the idea. In my view, leaving a corpse was not in our interest. To make it credible, we would have needed a shootout or confrontation with the police, which my orders specifically forbade.

SPIEGEL: So, with Heydrich’s orders, you set off toward Gleiwitz.

NAUJOCKS: Yes. I had 48 hours to prepare. I selected six or seven men.

SPIEGEL: All from the SD?

NAUJOCKS: Not all. For example, we needed someone fluent in Polish to deliver the speech, and also a skilled radio technician who could interrupt a live broadcast at an unfamiliar station. So, we traveled from Berlin to Gleiwitz in two cars and stayed in two separate hotels, disguised as civilians.

SPIEGEL: Did you train your men?

NAUJOCKS: No. They were already used to taking and carrying out orders. We were, in that sense, a semi-military unit.

SPIEGEL: What precautions did you take? Where did you get the text of the speech?

NAUJOCKS: I wrote it myself and had it translated into Polish. For me, the main concern was whether the transmitter was secure. But the station’s security was so lax it didn’t worry me.

SPIEGEL: How did you discover that?

NAUJOCKS: I scouted the grounds, especially the entrance. There were no guards, only a porter at the gate for part of the time. It was not difficult.

SPIEGEL: After the war, some said you posed as a merchant or postal worker to get inside the station.

NAUJOCKS: Fabrications. None of us ever entered the transmitter before the night of the action. But I was prepared to, if necessary.

SPIEGEL: So you waited for the cue from Berlin?

NAUJOCKS: Yes. A few days earlier, Heydrich warned me to be ready at any hour, and that I should report to SS-Oberführer Müller the same day.

SPIEGEL: Gestapo chief Müller?

NAUJOCKS: Yes. He came from Berlin to Oppeln. In that meeting I first heard the term “canned goods.”

SPIEGEL: The Nazi code name for concentration camp prisoners used as fake evidence of Polish attacks?

NAUJOCKS: Yes. Müller had central command over the operations in the border area. Since concentration camps were under the Gestapo, he could decide who was sent or released, without judicial review.

SPIEGEL: At Nuremberg, it was said these were “convicted criminals.”

NAUJOCKS: Müller told me they were professional criminals.

SPIEGEL: And Müller explained these “canned goods” would be used in your operation?

NAUJOCKS: Yes. He told me I would also receive one.

SPIEGEL: In Polish uniform?

NAUJOCKS: That was discussed, but I convinced him it wouldn’t work at Gleiwitz. Müller agreed and said the man would be in civilian clothes.

SPIEGEL: Was the timing already set?

NAUJOCKS: No. Both Müller and I were waiting for the signal. For us in Gleiwitz, the time was fixed at 8 p.m.—dark enough for cover, but early enough that people were still listening to the radio.

SPIEGEL: How would the prisoner be brought?

NAUJOCKS: Müller said: you begin at 8 p.m., and between 8 and 8:10 the “canned goods” will be delivered to the station.

SPIEGEL: Alive or dead?

NAUJOCKS: He didn’t say. I promised to leave two men outside to allow his agents access.

SPIEGEL: When did you finally get the green light?

NAUJOCKS: On August 31, around 4 p.m.—a direct call from Heydrich. The code phrase was: “Grandmother has died.”

SPIEGEL: Then you began.

NAUJOCKS: At 8 p.m. sharp, we entered the station. At gunpoint, we forced the staff—six or seven people—into the basement, where one of my men guarded them.

SPIEGEL: Did anyone raise the alarm?

NAUJOCKS: No. We had pistols and submachine guns. They didn’t resist. We searched for the microphone.

SPIEGEL: Did your technician have difficulties?

NAUJOCKS: Yes. We could only use the emergency “storm microphone.”

SPIEGEL: Did you pressure the staff?

NAUJOCKS: No. It wasn’t necessary.

SPIEGEL: Did you fire shots?

NAUJOCKS: Yes. We fired warning shots into the ceiling to create commotion and intimidate them.

SPIEGEL: How long did it last?

NAUJOCKS: About 20 minutes in total. The broadcast lasted four minutes.

SPIEGEL: And the guard in the basement?

NAUJOCKS: I had him recalled before we left.

SPIEGEL: Afterward, you saw the prisoner delivered by the Gestapo?

NAUJOCKS: Yes, lying near the entrance, his face covered in blood. I don’t know if he was dead or alive. I didn’t look closely—I wanted to leave quickly.

SPIEGEL: Could one of your men have shot him?

NAUJOCKS: No. I’m certain of that.

SPIEGEL: Later, the East German film The Gleiwitz Case depicted you as the killer.

NAUJOCKS: False. Completely fabricated.

SPIEGEL: Then who killed him?

NAUJOCKS: I can’t say. Perhaps he was killed by injection, as Müller once mentioned.

SPIEGEL: After the action, you returned to Berlin?

NAUJOCKS: No. We spent the night at the hotel.

SPIEGEL: Did you report to Berlin?

NAUJOCKS: Yes. But Heydrich was furious. He hadn’t heard the broadcast in Berlin, since Gleiwitz relayed the Breslau frequency. He accused me of lying.

SPIEGEL: Final question: What would you have done if the staff had resisted?

NAUJOCKS: Then we would have broken resistance—by force if necessary. But no one was beaten.

sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gleiwitz_incident

https://tvpworld.com/88613554/the-gleiwitz-incident-86-years-on-the-german-plot-that-sparked-wwii

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Himmler

https://www.tracesofwar.com/articles/7876/Gleiwitz-incident.htm

https://www.thecollector.com/gleiwitz-incident-nazis-faked-attack-germany/

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a reply to tzipporahbatami Cancel reply