The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was one of the most significant judicial efforts to hold individuals accountable for crimes committed during war. Established in the aftermath of World War II, the tribunal sought to prosecute the leading figures of Imperial Japan for crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Convened on May 3, 1946, and concluding on November 12, 1948, the tribunal stood as a defining moment in international criminal justice. It not only exposed the brutal realities of Japan’s wartime aggression but also set enduring legal precedents for how the international community deals with atrocities and the responsibilities of state leaders.

Background and Context

The roots of the IMTFE lie in the broader Allied effort to punish Axis leaders for their roles in starting and conducting a war of aggression. As early as 1943, at the Moscow Conference (October 19–30, 1943), the Allies had agreed that those responsible for atrocities committed by Axis powers would face justice. After the Allied victory in Europe, the Nuremberg Trials were established in November 1945 to prosecute Nazi leaders. In Asia, a similar tribunal was conceived to address Japan’s war crimes.

Following Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945, after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima (August 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (August 9, 1945) and the Soviet declaration of war on Japan (August 8, 1945), the Allies occupied Japan under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, who served as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP). One of MacArthur’s key responsibilities was to ensure the prosecution of Japanese leaders who had led the country into aggressive wars and sanctioned atrocities throughout East and Southeast Asia.

On January 19, 1946, MacArthur issued a special proclamation establishing the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. The tribunal’s Charter, known as the Charter of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (CIMTFE), defined its jurisdiction and procedures. It closely mirrored the Nuremberg Charter (August 8, 1945) and specified three categories of crimes:

- Class A (Crimes against Peace): Planning, preparing, initiating, or waging wars of aggression in violation of international treaties.

- Class B (War Crimes): Conventional violations of the laws or customs of war.

- Class C (Crimes against Humanity): Inhumane acts committed against civilian populations before or during the war.

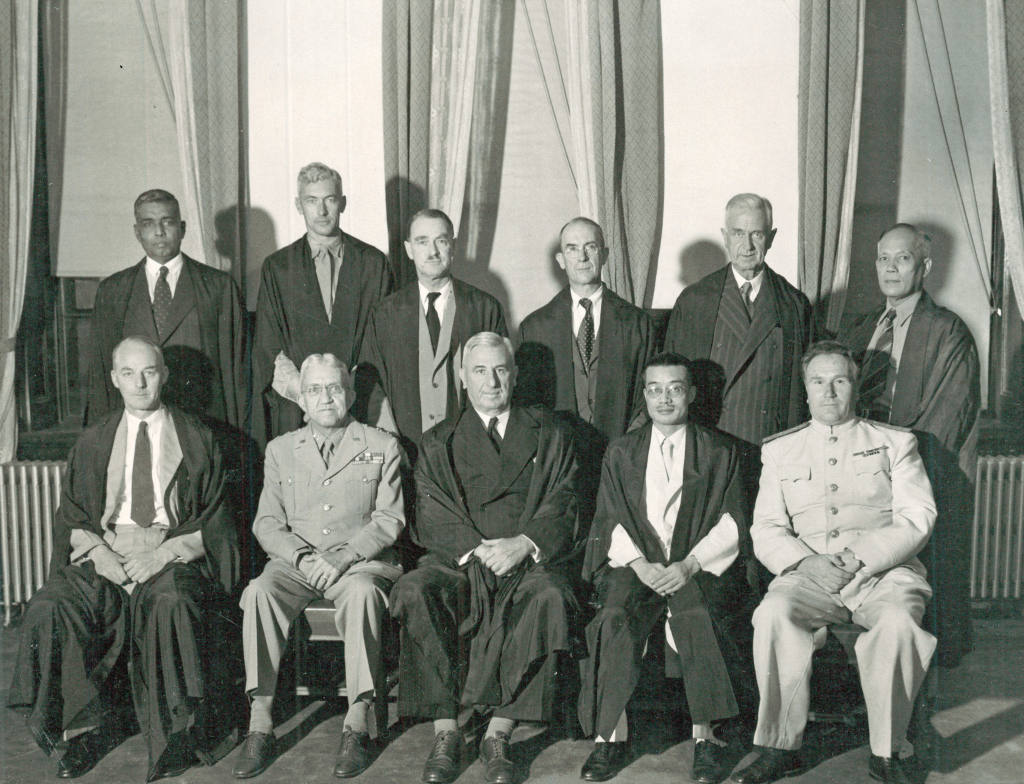

Structure and Composition of the Tribunal

The IMTFE consisted of eleven judges, each representing one of the Allied powers that had participated in the Pacific War. The judges and their respective countries were:

- Justice Sir William Webb (Australia) – President of the Tribunal

- Justice Myron C. Cramer (United States)

- Justice Henri Bernard (France)

- Justice Edward Stuart McDougall (Canada)

- Justice Delfín Jaranilla (Philippines)

- Justice Mei Ju-ao (China)

- Justice I.M. Zaryanov (Soviet Union)

- Justice Radhabinod Pal (India)

- Justice Erima Harvey Northcroft (New Zealand)

- Justice Lord Patrick (United Kingdom)

- Justice B.V.A. Röling (Netherlands)

The Chief Prosecutor, Joseph B. Keenan (United States), headed an international team of prosecutors drawn from the Allied nations. The tribunal convened at the War Ministry Building in Tokyo — today’s Ichigaya district — and began hearings on May 3, 1946.

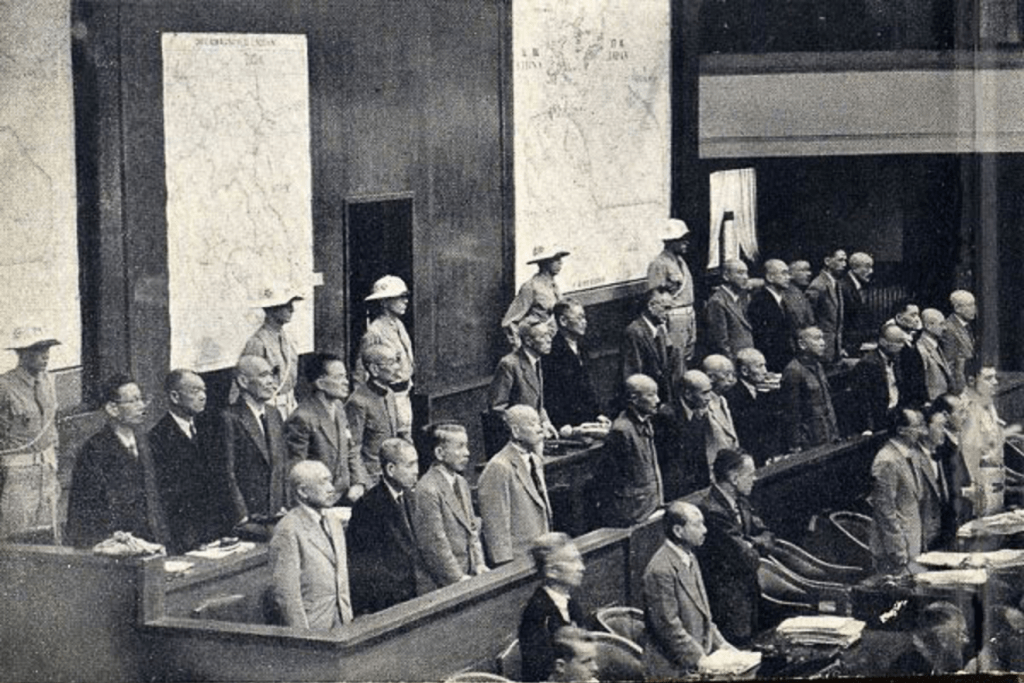

The Defendants and Charges

A total of 28 high-ranking Japanese leaders were indicted on April 29, 1946. The list included key political, military, and diplomatic figures, such as:

- Hideki Tojo, former Prime Minister and Army General

- Koki Hirota, former Prime Minister and Foreign Minister

- Shigenori Togo, Foreign Minister during the attack on Pearl Harbor

- Kenji Doihara, Army General and intelligence officer

- Seishirō Itagaki, Army General and Minister of War

- Heitarō Kimura, Army General

- Iwane Matsui, General associated with the Nanjing Massacre (December 1937 – January 1938)

The indictment, filed on April 29, 1946, contained 55 counts divided into three classes. The most serious were the Class A charges, which alleged a conspiracy dating back to 1928 to dominate East Asia and the Pacific through aggressive warfare. Specific reference was made to Japan’s invasions of Manchuria (September 1931), China (1937), and the attacks on the United States (Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941) and the British Empire (Malaya, Hong Kong, and Singapore, December 1941–February 1942).

Proceedings and Key Evidence

The trial proceedings lasted for more than two and a half years, making it one of the longest trials in legal history. The prosecution presented an enormous volume of evidence — over 400 witnesses, 4,000 exhibits, and 48,000 pages of testimony. Much of the evidence detailed Japan’s aggression and atrocities in China, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific islands.

One of the most harrowing episodes discussed during the trial was the Nanjing Massacre (also known as the Rape of Nanking), in which an estimated 200,000–300,000 Chinese civilians were killed by Japanese troops between December 1937 and February 1938. The tribunal also examined the mistreatment of prisoners of war, including the Bataan Death March (April 9–17, 1942) in the Philippines, where thousands of captured American and Filipino soldiers died from starvation, dehydration, and abuse.

The defense argued that Japan’s wars were acts of self-defense, driven by the need for raw materials and security against Western imperialism. They also claimed that the tribunal applied retroactive justice, as the concept of “crimes against peace” had not been established under international law before the war. Despite these arguments, the majority of judges upheld the legitimacy of the charges.

Judgment and Sentencing

After more than 817 court sessions, the tribunal delivered its judgment on November 12, 1948. All 25 remaining defendants were found guilty on at least one count (three had died or were incapacitated during the trial). Seven men were sentenced to death by hanging, sixteen received life imprisonment, and two received lesser sentences. The sentences were as follows:

Sentenced to Death (Executed on December 23, 1948):

- Hideki Tojo – Former Prime Minister and General

- Seishirō Itagaki – General and War Minister

- Kenji Doihara – General and intelligence officer

- Heitarō Kimura – General and commander in Burma

- Iwane Matsui – General responsible for Nanjing

- Akira Muto – General and chief of staff in the Philippines

- Koki Hirota – Former Prime Minister and Foreign Minister

Sentenced to Life Imprisonment:

Included Shigenori Togo, Yosuke Matsuoka, Naoki Hoshino, and others. Several, including Matsuoka and Hiranuma, died in prison in the early 1950s.

The executions were carried out at Sugamo Prison, Tokyo, in the early hours of December 23, 1948 — coincidentally, the birthday of Crown Prince Akihito (later Emperor Akihito), which many saw as symbolically complex.

Criticisms and Controversies

The IMTFE, though pioneering, was not without criticism. One of the most vocal critics was Justice Radhabinod Pal (India), who issued a dissenting opinion exceeding 1,200 pages, arguing that all defendants should be acquitted. He claimed the trial represented “victor’s justice”, as only the defeated Japanese were prosecuted, while Allied war crimes — such as the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the firebombing of Tokyo (March 9–10, 1945) which killed over 100,000 civilians — were ignored.

Another controversy surrounded the immunity of Emperor Hirohito and members of the imperial family. Despite evidence of their involvement in Japan’s militarization, the U.S. occupation authorities, led by General MacArthur, decided not to indict the Emperor, fearing that his prosecution might destabilize Japan’s postwar reconstruction.

Critics also questioned the tribunal’s legitimacy due to its retroactive application of international law — particularly regarding “crimes against peace,” a concept that had not been codified before 1939. Moreover, some argued that the tribunal overlooked the broader political and economic causes of Japan’s militarism, focusing instead on a narrow set of individuals.

Impact and Legacy

Despite its controversies, the Tokyo Tribunal established vital precedents in international criminal law. It reinforced the principle of individual responsibility — that government leaders and military commanders could not escape liability for crimes committed under their authority. The tribunal’s jurisprudence influenced later institutions, including:

- The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) (1993)

- The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) (1994)

- The International Criminal Court (ICC) (established in 2002 under the Rome Statute)

The IMTFE also contributed to Japan’s postwar identity. The tribunal’s findings helped shape the Japanese Constitution of 1947, particularly Article 9, which renounces war as a sovereign right. However, domestic debate over the tribunal continues. Some Japanese conservatives view the IMTFE as a politically motivated instrument of occupation, while others see it as a necessary reckoning that helped Japan rebuild as a peaceful democracy.

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East marked a turning point in the history of global justice. Between May 3, 1946, and November 12, 1948, the tribunal sought to impose accountability on those who had led Japan into one of the darkest chapters in modern history. Though flawed in procedure and limited in scope, it symbolized a major step toward a world where acts of aggression, mass atrocities, and crimes against humanity could no longer be committed with impunity.

The IMTFE’s legacy endures not only in legal institutions but also in the moral conscience of the international community. It remains a testament to the belief — however imperfectly realized — that justice must extend beyond the battlefield, and that even in the aftermath of global conflict, the rule of law must prevail.

sources

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/topics/tokyo-war-crimes-trial

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Military_Tribunal_for_the_Far_East

https://imtfe.law.virginia.edu/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Military_Tribunal_for_the_Far_East

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment