The Buna-Monowitz Concentration Camp, part of the Auschwitz complex, was established to support the labor demands of IG Farben, a German chemical company. Prisoners were forced into grueling labor, constructing and operating facilities for the production of synthetic rubber and fuel. Conditions were brutal: malnutrition, disease, and the constant threat of violence characterized daily life.

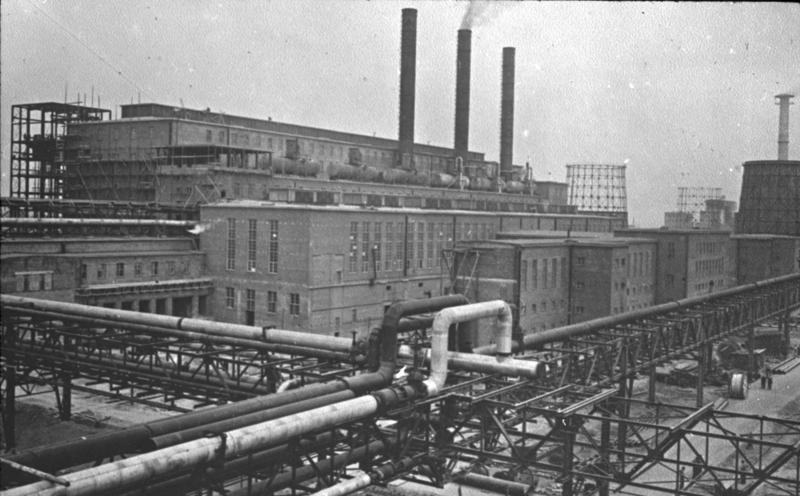

On 22 February 1941, IG Farben approved plans to build the Buna-Werke synthetic rubber plant near Auschwitz concentration camp, a location chosen to exploit forced labour and to reduce vulnerability to Allied air raids.

During the Second World War, the relationship between German industry and the Nazi state reached an unprecedented level of integration. Few examples illustrate this convergence more starkly than the decision by IG Farben to construct its synthetic rubber and fuel complex—known as the Buna-Werke—adjacent to Auschwitz concentration camp. The project demonstrates how economic ambition, ideological alignment, and wartime strategy combined to produce one of the most disturbing partnerships between private enterprise and state-sponsored violence in modern history.

Industrial Strategy and Wartime Necessity

Germany entered the war with a critical strategic weakness: limited access to natural resources, particularly rubber and petroleum. Synthetic substitutes became essential to sustaining military operations. IG Farben, Europe’s largest chemical corporation, had already pioneered synthetic rubber (“Buna”) technology during the interwar period. As the war intensified, the German government—dominated by the Nazi Party—prioritized massive expansion of synthetic production facilities.

The location near Auschwitz offered several advantages from the regime’s perspective. Upper Silesia provided rail connectivity, coal supplies, and water resources necessary for heavy chemical manufacturing. Equally important, however, was the availability of an immense captive labor force drawn from the camp system. Industrial planning and state repression thus became mutually reinforcing components of wartime policy.

Forced Labor and Auschwitz III–Monowitz

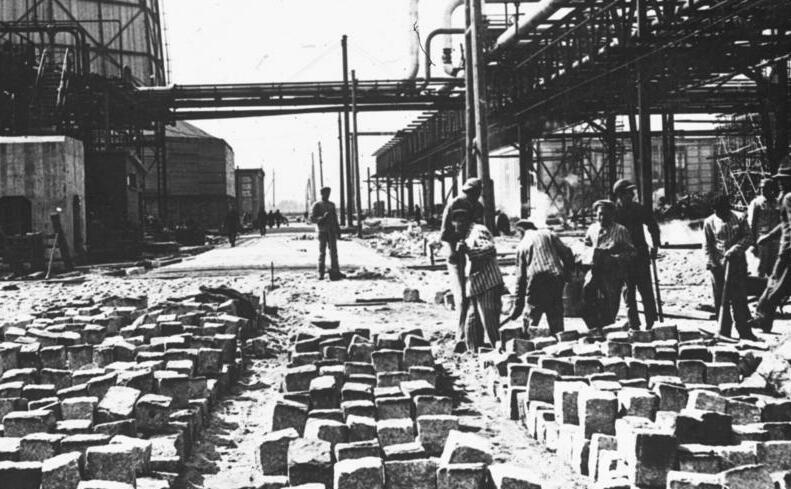

To serve the factory, a new subcamp—commonly called Monowitz or Auschwitz III—was established under the authority of the Schutzstaffel (SS). Prisoners, many of them Jews deported from across occupied Europe, were leased to IG Farben as forced laborers. The company paid the SS daily rates per worker, effectively transforming human beings into industrial inputs.

Conditions were catastrophic. Workers endured starvation rations, exposure, brutal discipline, and exhausting construction labor. Mortality rates were extraordinarily high; prisoners deemed too weak to work were routinely sent back to the main camp, where many were murdered. The Buna-Werke never achieved full production before the war ended, yet tens of thousands suffered and died in its construction and operation.

There are no estimates of the number of prisoners of the Buna-Außenkommando who died between April 1941 and July 1942. From October 1942 onward, based on survivor accounts, the estimated number of deaths fluctuates between 23,000 and 40,000. Many perished at the construction site in work-related accidents, often due to the complete absence of safety measures. The majority, however, died of cachexia resulting from malnutrition, extreme overwork, and untreated diseases.

At the instigation of IG Farben managers, prisoners deemed unable to work—whether due to prolonged illness or invalidity—were selected for the gas chambers in Birkenau. Routine selections occurred in the mornings at the camp gate as prisoners marched to work, in the infirmary, or at the roll-call square. Those involved included the camp commandant, the protective custody camp leader, SS members responsible for labor allocation, the SS camp physician, and, according to a surviving prisoner-physician, several IG Farben civilian employees. Selections in the infirmary were initiated whenever more than five percent of the inmates were sick. The average prisoner survived only three to four months in Monowitz.

In response to this daily brutality, one of the main objectives of the camp resistance was to save lives. The resistance sought to provide extra food and medicine, improve living conditions, and offer political education. An international network, primarily composed of Poles and Jews from Germany and Austria, led the resistance. Members secured key administrative positions within the camp, allowing them to gather intelligence and influence events.

Within the IG Farben factory, prisoners secretly contacted civilian employees, forced laborers, and prisoners of war to exchange information and coordinate sabotage efforts, which delayed the completion of the plant. For example, the electricians’ Kommando successfully caused a short circuit in the turbines during a test run. According to Walter Petzold, a former prisoner, the resistance also prevented IG Farben from starting synthetic fuel production during the so-called Day of National Work on 1 May 1943. Three days earlier, prisoners had sabotaged the high-pressure station, and in the vehicle park, they destroyed 50 trucks and tractors through deliberate damage.

After attempted escapes, prisoners were subjected to prolonged roll calls as punishment. Those who were recaptured faced hanging, often in full view of the camp inmates, who were forced to witness the executions.

Strategic Calculations and Bombing Considerations

The factory’s placement also reflected wartime security calculations. Industrial planners believed that proximity to a concentration camp complex—and its location deep within occupied territory—reduced the likelihood of sustained attack by the Allied Forces. While Allied aircraft eventually targeted nearby industrial infrastructure, large-scale bombing of Auschwitz itself remained limited and controversial, influenced by intelligence gaps, competing military priorities, and uncertainty about the camp’s full function.

The assumption that the site would enjoy relative protection illustrates how economic and military logic intersected with moral blindness. Industrial managers pursued efficiency and continuity of production while disregarding the human reality underpinning their workforce.

Corporate Responsibility and Moral Complicity

The Buna project raises enduring questions about corporate ethics under authoritarian regimes. IG Farben executives were not merely passive participants compelled by state coercion; archival evidence shows active negotiation with SS authorities over labor supply, camp expansion, and production quotas. Profit expectations and technological ambition aligned with the regime’s exploitation policies.

After the war, several company leaders were prosecuted in the IG Farben Trial at Nuremberg. Although sentences were comparatively lenient, the proceedings established an important legal and moral precedent: private corporations can bear responsibility for crimes against humanity when they knowingly benefit from systematic abuse.

Over time, more than 90 percent of the inmates at Monowitz were Jewish prisoners deported from Germany, Austria, Poland, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Norway, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, and Czechoslovakia. The majority of non-Jewish prisoners were citizens of Poland, the Soviet Union, and Germany. Approximately 1–2 percent of the camp population consisted of Roma and Sinti prisoners of uncertain nationality.

Following a series of successful escapes during the summer of 1943, the SS transferred many Polish and Czechoslovak prisoners to Buchenwald concentration camp and Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where foreign prisoners generally faced significantly lower chances of survival after escape attempts.

The mass deportation of Hungarian Jews in the spring and summer of 1944 substantially increased their proportion within the camp population.

Historical Significance

The Buna-Werke stands as a powerful case study in the dangers of subordinating ethical judgment to industrial and strategic objectives. It demonstrates that modern atrocities are rarely carried out by governments alone; they often depend on administrative systems, technical expertise, and commercial actors willing to cooperate.

Today, the history of IG Farben at Auschwitz serves as a warning about the potential consequences when economic rationality becomes detached from human values. The factory’s unfinished structures and documented suffering remain evidence that technological progress and organizational efficiency, without moral restraint, can become instruments of profound destruction.

The Buna-Werke factory complex was bombed by Allied forces on four occasions between August and December 1944, causing significant damage to several industrial buildings. Although limited quantities of products such as synthetic fuel and oil were manufactured, the war ended before the plant’s intended primary product — synthetic rubber — entered full production.

Factory operations ceased in mid-January 1945. Shortly thereafter, the site was overrun, and the remaining prisoners held in the associated labour camps were liberated by the Soviet Army on 27 January 1945.

The principal workers’ camps established to support the IG Farben Buna-Werke complex near Auschwitz concentration camp were numbered and designated as follows. Some functioned as forced-labour camps for prisoners, while others served as residential barracks for civilian employees recruited by IG Farben:

Lager I – Leonhard Haag: civilian workers, primarily Germans, as well as Italians and later Italian prisoners of war.

Lager II – Buchenwald: forced labourers from Poland, Ukraine, and Russia.

Lager III – Teichgrund: German and Polish civilian workers together with forced labourers from the Soviet Union.

Lager IV – Dorfrand: later known as the “Buna” camp and subsequently the main Monowitz camp, which administered the others; housed Jewish concentration-camp prisoners.

Lager V – Tannenwald: German and Polish civilian workers alongside forced labourers from Croatia and the Soviet Union.

Lager VI – Pulverturm: German civilian workers, with a separate section for British prisoners of war designated Lager E715.

Lager VII – Angestellten Wohnlager: German civilian workers.

Lager VIII – Karpfenteich: initially British prisoners of war, later replaced by German civilian workers.

Lager IX: designation recorded, specific function unclear.

Lager X: designation recorded, specific function unclear.

Jugendwohnlager (Lehrlingsheim): accommodation for German and Silesian boys undergoing training as IG Farben apprentices.

Jugendwohnheim-Ost: located adjacent to the Jugendwohnlager; housed girls affiliated with the Bund Deutscher Mädel and female auxiliary labour units of the Reichsarbeitsdienst.

On January 18, 1945, Monowitz was evacuated. Approximately 800 to 850 sick prisoners, too weak to leave, were left behind. The remaining prisoners—around 10,000—were forced on a brutal death march. Many thousands perished from exhaustion, exposure, and starvation, or were beaten or shot by the SS when unable to continue. The march west passed through Mikolów to Gleiwitz, where the survivors were loaded onto open cattle cars and transported to concentration camps in the Reich. Many ultimately ended up in Mittelbau, where they were forced to work underground in German rocket production. The prisoners left behind in Monowitz were liberated by the 60th Army of the Red Army’s First Ukrainian Front on January 27, 1945.

The crimes committed at Monowitz were documented in detail for the first time during the U.S. Military Tribunal at Nürnberg in Case 6 (1947–1948), where 24 top managers of IG Farben were charged with plunder, despoilation, and the use of civilian, POW, and concentration camp slave labor. Five managers received sentences of six to eight years for exploiting and enslaving Auschwitz inmates. Ten defendants were acquitted, and one was released during the trial for health reasons. Of the 13 IG Farben managers sentenced as war criminals, four were immediately released, and the others served only part of their sentences.

Shortly after the war, several members of the SS were sentenced to death by Allied Military Tribunals for crimes committed in concentration camps. Among them were the former Monowitz Lagerführer, SS-Obersturmführer Vinzenz Schöttl, sentenced at the Dachau trial (1945), and the former camp physicians SS-Obersturmführer Friedrich Entress and SS-Hauptsturmführer Helmuth Vetter, sentenced at the Mauthausen trial (1946). A French Military Tribunal at Rastatt sentenced the former commandant of Monowitz, Schwarz, to death in 1946 for crimes committed at Natzweiler.

Under Allied control, IG Farben was dismantled and split into successor firms: Badische Anilin und Sodafabrik (BASF), Hoechst, Bayer, Casella, and IG Farbenindustrie in Liquidation. Norbert Wollheim was the first survivor to claim compensation against IG Farbenindustrie in Liquidation in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). The Wollheim proceedings began in January 1952 and concluded in 1957 with the involvement of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. A private settlement was reached out of court, with 30 billion Deutsche Mark (DM) paid in compensation for slave labor at the IG Farben factories in Monowitz, Heydebreck, Fürstengrube, and Janinagrube. IG Farbenindustrie in Liquidation maintained that the payments were voluntary, without legal obligation, leaving many survivors unaware of the claims deadline. The Wollheim agreement later became a model for compensating former slave laborers in other cases against German industry.

Only a few perpetrators were tried in the 1950s and 1960s in the FRG and German Democratic Republic (GDR) for crimes committed at Monowitz. Bernhard Rakers, former Kommandoführer and Rapportführer at Monowitz, was tried multiple times from 1950 onward for shooting prisoners during the death march and ultimately sentenced to life imprisonment by the Landgericht Osnabrück. In the GDR, former SS-Lagerarzt Horst Fischer was arrested in June 1965 near Frankfurt an der Oder. He was accused of participating in the selection of thousands of prisoners, confessed to the crimes, and was sentenced to death by the Supreme Court of the GDR on March 25, 1966; he was executed later that year.

In the first Auschwitz trial (December 1963–August 1965) in Frankfurt am Main, former Sanitätsdienstgrad Gerhard Neubert was released for health reasons. In the second Auschwitz trial (1966), he was sentenced to three and a half years for accessory to murder in 35 selections. In the third Auschwitz trial (August 1966), Erich Grönke, Heinrich Bernhard Bonitz, and Josef Windeck were charged with murder. Bonitz, a former block elder and Kapo at Monowitz, received a life sentence. Windeck, former camp elder, was sentenced to life imprisonment for two murders and three attempted murders. Preliminary proceedings against Stefan Buthner, former camp elder of the hospital (Krankenbau), opened in 1966, were closed in 1975 due to contradictory witness testimony.

sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monowitz_concentration_camp

https://muse.jhu.edu/document/1375

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2008-08-13/ig-farben-and-hitler-a-fateful-chemistry

https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn723153

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment