Americans and the Holocaust is an exhibition at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, which opened on 23 April 2018. Before I go into the details of this exhibition, I want to mention one of the few Americans, Eddy Hamel, who was murdered during the Holocaust.

Eddy Hamel was the first Jewish player, and also the first American, to play for Ajax in Amsterdam. Born in New York City in 1902, he had moved to the Netherlands as a baby with his Dutch-born parents and considered himself more Dutchman than American.

Hamel became a first-team regular for Ajax, to date, only four other Jewish soccer players have followed in his footsteps—Johnny Roeg, Bennie Muller, Sjaak Swart, and Daniël de Ridder. Hamel was a fan favourite and was cited by pre-World War II club legend Wim Anderiesen as part of the strongest line-up he ever played with. He had his fan club in the 1920s, which would line up on his side of the field at the beginning of every game and then switch sides—to be on the side of the field he was on during the second half. After his retirement as a player, Hamel managed Alcmaria Victrix for three years and continued to play in an Ajax veteran squad.

Hamel became a first-team regular for Ajax, to date, only four other Jewish soccer players have followed in his footsteps—Johnny Roeg, Bennie Muller, Sjaak Swart, and Daniël de Ridder. Hamel was a fan favourite and was cited by pre-World War II club legend Wim Anderiesen as part of the strongest line-up he ever played with. He had his fan club in the 1920s, which would line up on his side of the field at the beginning of every game and then switch sides—to be on the side of the field he was on during the second half. After his retirement as a player, Hamel managed Alcmaria Victrix for three years and continued to play in an Ajax veteran squad.

Hamel, his wife and their sons lived across town at the time, not far from where 13-year-old Anne Frank and her family lived. In apparent defiance of the rules of the Nazi regime, Hamel continued to play for his old team. Lucky Ajax, during the German occupation.

On 27 October 1942, Hamel was stopped by two officers from the Jewish Affairs division of the Amsterdam Police Department, which collaborated with the Nazis. The arrest report, written in German, states that Hamel told his captors he was born in New York. He gave coaching as his profession. The reason for the arrest: He was caught in public ohne judenstern—without his Jewish star. Despite his American citizenship, Hamel was detained by the Nazis because he was a Jew.

Eddy and his family had to report to Westerbork. They ended up in the so-called English Barrack. There were British and American citizens who were eligible for exchange. But that status turned out to offer no protection either. Leon Greenman, who was in the same barracks, spent the last few months with Eddy. Both their families were deported to Auschwitz in January 1943, where the women and children were immediately murdered. Both men were to work.

Eddy spent four months doing hard labour at Birkenau. After he was found to have a swollen mouth abscess during a Nazi inspection, the Nazis sent him to the gas chambers in Auschwitz concentration camp on April 30, 1943, where they murdered him.

AMERICANS AND THE HOLOCAUST

By the time Nazi Germany forced the world into war, democratic civilization was at stake. The US military fought for almost four years to defend democracy, and 400,000+ Americans died. The United States alone could not have prevented the Holocaust, but more could have been done to save some of the lives of the six million Jews killed.

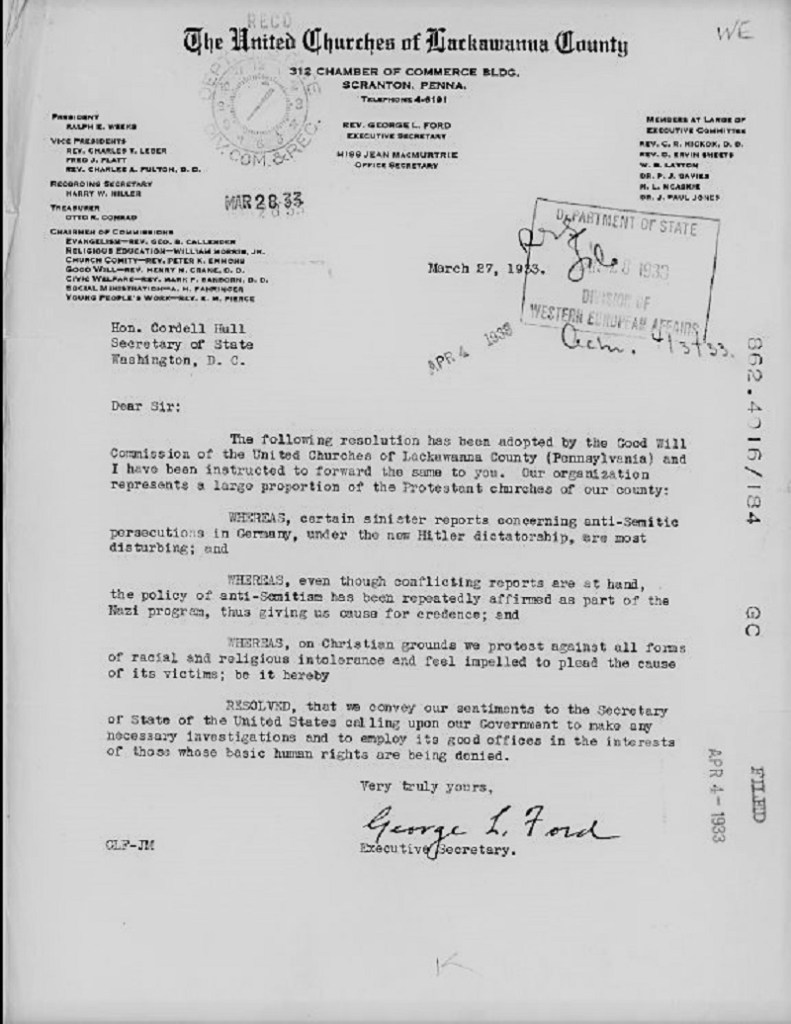

It was already known in 1933 what was happening in Germany. The photograph at the top of this post is from a resolution sent on 27 March 1933 by the United Churches of Lackawanna County in Scranton, Pennsylvania, to US Secretary of State Cordell Hull.

After Kristallnacht, Gallup asked Americans: Do you approve or disapprove of the Nazi treatment of Jews in Germany? Of the vast majority who responded, 94% indicated disapproval. Yet, although nearly all Americans condemned the Nazi regime’s terror against Jews in November 1938, that very same week, 72% of Americans said, No when Gallup asked: Should we allow Jewish exiles from Germany to come to the United States to live?—only 21% answered Yes.

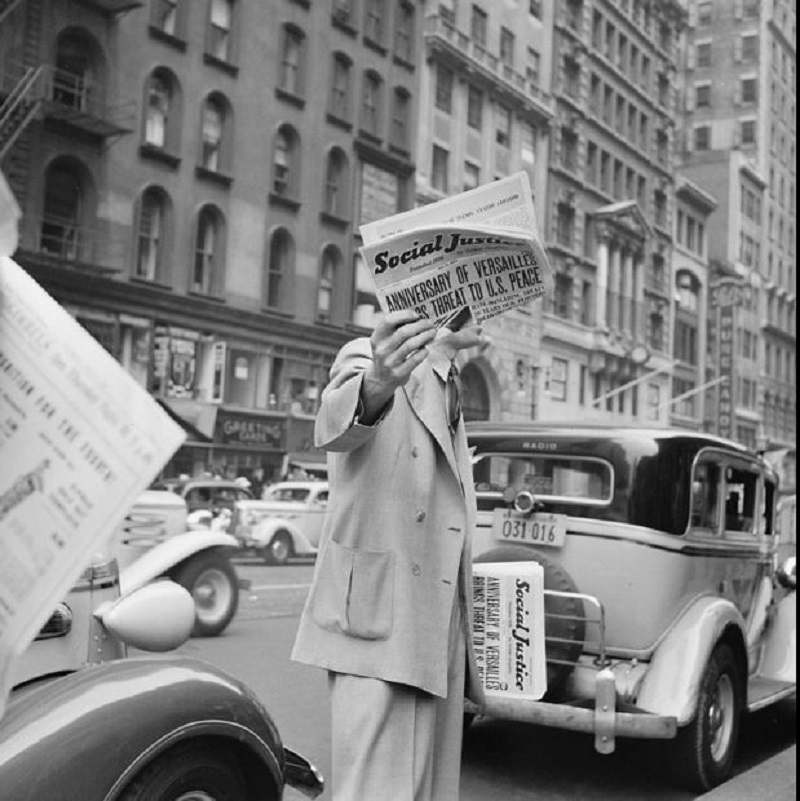

Prejudice against Jews in the U.S. was evident in several ways in the 1930s. According to historian Leonard Dinnerstein, more than 100 new anti-Semitic organizations were founded in the U.S. between 1933 and 1941. One of the most influential, Father Charles Coughlin’s National Union for Social Justice, spread Nazi propaganda and accused all Jews of being communists. Coughlin broadcast anti-Jewish ideas to millions of radio listeners, asking them to pledge to restore America to the Americans.

On 20 November 1938, two weeks after Kristallnacht, Coughlin, referring to the millions of Christians killed by the Communists in Russia, said, “Jewish persecution only followed after Christians first were persecuted.”

Further to the fringes, William Dudley Pelley’s Silver Legion of America (“Silver Shirts”) fashioned themselves after Nazi Stormtroopers (“brownshirts”). The German American Bund celebrated Nazism openly, established Hitler Youth-style summer camps in communities across the United States and hoped to see the dawn of fascism in America.

Even if the Silver Shirts and the Bund did not represent the mainstream, Gallup polls showed that many Americans held seemingly prejudicial ideas about Jews. A remarkable survey conducted in April 1938 found that more than half of Americans blamed Europe’s Jews for their own treatment at the hands of the Nazis. This poll showed that 54% of Americans agreed that “the persecution of Jews in Europe has been partly their own fault,” with 11% believing it was “entirely” their own fault. Hostility to refugees was so ingrained that just two months after Kristallnacht, 67% of Americans opposed a bill in the U.S. Congress intended to admit child refugees from Germany. The bill never made it to the floor of Congress for a vote.

Fritz Kuhn, a German veteran of World War I, was the leader (or Bundesfuher) of the German-American Bund. After World War I, Kuhn immigrated first to Mexico and then to the United States, where he became a naturalized citizen in 1934. At its height—the Bund had organized 20 youth training camps and were promoted as family-friendly summer camps—Camp Siegfried in Long Island, Camp Hindenberg in Wisconsin, and Deutschhorst Country Club in Pennsylvania. They were devoted to projecting favourable views of Nazi Germany and spreading Nazi ideology in the United States. The camps’ popularity increased rapidly. The New Jersey division of the Bund opened its 100-acre Camp Norland at Sussex Hills in 1937, and the annual German Day festivities at Camp Siegfried in Long Island attracted 40,000 people in 1938.

Even during World War II, the American public realized that the rumours of mass murder in death camps were true—struggling to grasp the vast scale and scope of the crime. In November 1944, well over 5 million Jews had been murdered by the Nazi regime and its collaborators. Yet just under one-quarter of Americans who answered the poll could believe that more than 1 million people had been murdered by Germans in concentration camps; 36% believed that 100,000 or fewer had been killed.

Below is an interview with Dr. Daniel Greene, the guest exhibition curator at the museum, where he talks about further polls in the exhibition Americans and the Holocaust.

Finishing up with the story of another Jewish American. He did not die in any of the concentration camps, but he died on the battlefield.

Leo Lichten was born on 31 May 1925, in Manhattan, the son of Max and Mollie Lichten. He grew up in Brooklyn, New York, and his best buddy, Paul, described him as “a very noble, intelligent and courageous person.” He even saved Paul from drowning once when they were kids.

Pfc Leo Lichten entered the service in New York, New York on 11 August 1943. Leo’s company, Company A, was ordered on 20 November 1944, to attack pillboxes (small bunkers) just outside Prummern to eliminate the enemy resistance in the small German town.

The weather was cold and rainy, the ground was muddy, and it made the battle even more difficult than it might otherwise have been. Leo stormed one of the pillboxes and was killed by machine gun fire early on in the battle.

He was laid to rest in the Netherlands American Cemetery and Memorial in Margraten, along with 8,300 fellow US soldiers and the names of 1,700 others who went missing in action.

I know there was a lot to read and listen to in this post, but it is important that these stories are remembered and retold.

Sources

https://www.si.com/soccer/2019/02/12/eddy-hamel-ajax-american-holocaust-victim-auschwitz

https://en.margratenmemorial.nl/dossier/leo-lichten/overview.html

https://exhibitions.ushmm.org/americans-and-the-holocaust/main

https://news.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/232949/american-public-opinion-holocaust.aspx

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment