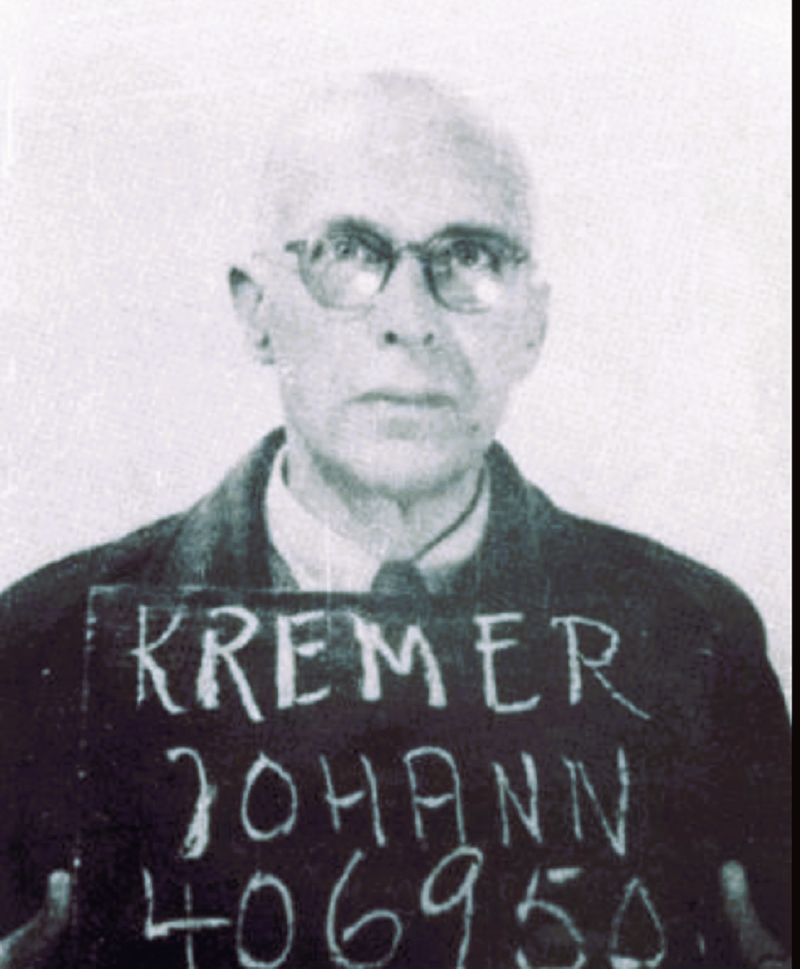

Dr. Johann Paul Kremer was a German physician and professor of anatomy who became infamously known for his role as an SS physician at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp during the Holocaust. Born on December 26, 1883, in Stellberg, Germany, Kremer was highly educated and had a background in medicine and anatomy, working as a professor at the University of Münster. However, his career took a dark turn when, during World War II, he was assigned to serve at Auschwitz, where he participated in some of the most horrific aspects of the Nazi genocide.

Kremer’s time at Auschwitz was brief—he served there for only a few months in 1942—but his involvement in the atrocities, as well as the detailed diary he kept during this time, has made him a significant figure in Holocaust history. His diary provides chilling insight into the mind of a Nazi physician, highlighting the moral depravity and detachment with which the perpetrators of the Holocaust approached their crimes.

Early Life and Education

Before the war, Dr. Kremer had an illustrious academic career. He studied medicine and earned a doctorate in natural sciences with a specialization in anatomy. He became a professor at the University of Münster, where he focused on medical research, particularly in fields related to human physiology and genetics.

Kremer’s decision to join the Nazi Party and later the SS in the 1930s aligned him with the ideology that supported eugenics, racial hygiene, and, eventually, genocide. His involvement in these institutions laid the foundation for his later participation in the atrocities committed at Auschwitz.

Role at Auschwitz

In August 1942, Kremer was drafted into the Waffen-SS and sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest Nazi concentration and extermination camp. His primary duties at the camp were as a camp physician, responsible for overseeing selections of prisoners arriving by train, determining who would be sent to forced labor and who would be sent directly to the gas chambers. He also performed various medical experiments and autopsies on prisoners, particularly those suffering from malnutrition and disease, which provided the opportunity for his research interests in anatomy.

Kremer’s time at Auschwitz occurred during a fierce phase of the camp’s operation, known as Aktion Reinhard, the codename for the mass extermination of Polish Jews. During this period, the number of arrivals at Auschwitz increased dramatically, and the gas chambers and crematoria were operating at total capacity.

Selections

Kremer was involved in the selection process of prisoners, where he stood at the railway platform as trains full of Jewish deportees arrived. Prisoners were divided into two groups: those considered fit for labor, who would be temporarily spared, and those deemed unfit, including the elderly, sick, children, and pregnant women, who would be sent directly to the gas chambers.

Kremer described these selections in his diary in cold, clinical terms. On September 5, 1942, he noted the horrors of the camp’s operations, describing the arrival of prisoners and the selection process as routine, showing little personal moral conflict about the mass murder taking place.

Medical Experiments and Autopsies

Kremer’s medical work at Auschwitz also involved conducting medical experiments on prisoners, many of whom were already suffering from malnutrition and disease. He showed particular interest in hunger experiments, observing and documenting the effects of extreme starvation on the human body. These experiments were meant to study the effects of starvation and validate Nazi racial ideology by dehumanizing the camp’s victims.

In addition to experiments, Kremer performed autopsies on prisoners, focusing on those who had died of diseases like typhus and dysentery, or those who had been selected for medical experimentation. His autopsy reports reflect the pseudoscientific racial theories that permeated Nazi medical practices, treating the victims not as humans but as subjects for research.

Kremer’s Diary: A Chilling Document

Kremer’s diary, which he kept during his time at Auschwitz, is one of the most important primary sources that document the daily operations and mindset of an SS physician involved in the Holocaust. The diary entries are brief and often stark in their detachment. Yet, they offer a chilling glimpse into the routine horrors of the camp from the perspective of a perpetrator.

One of the most infamous entries—dated September 2, 1942, describes a day when Kremer witnessed the gassing of prisoners at Birkenau. He wrote:

- “For the first time, at 3 a.m., I attended a special action. Compared to this—Dante’s Inferno seems almost a comedy.”

This passage reveals not only Kremer’s awareness of the atrocities but also the grotesque normalization of mass murder that had taken root in the minds of many camp officials. His diary entries show no moral reflection or remorse but instead, convey a clinical fascination with the events unfolding before him.

On other occasions, Kremer’s diary notes the “special actions” (a Nazi euphemism for gassings), selections, and the physical conditions of the prisoners. Despite witnessing these horrors, his primary focus in the diary often returns to mundane personal matters, such as his meals or the weather, reflecting a disturbing detachment from the human suffering surrounding him.

Diary as Historical Evidence

Kremer’s diary is significant for several reasons:

- Direct Insight into Atrocities: It provides first-hand documentation of the selection process and mass murder at Auschwitz.

- Psychological Detachment: The way Kremer casually describes the most horrific scenes demonstrates the complete moral and emotional detachment of Nazi officials who had become desensitized to the atrocities they were committing.

- Pseudoscientific Focus: His diary reveals the distorted mindset that allowed Nazi doctors to frame their participation in genocide as scientific work, reinforcing the regime’s racial ideology.

- Indictment of Nazi Medical Ethics: Kremer’s writings stand as an indictment of how Nazi physicians abused their profession to advance the genocidal aims of the regime, abandoning the Hippocratic Oath in favor of a perverse racial pseudoscience.

Post-War Trial and Conviction

After the fall of Nazi Germany in 1945, Johann Paul Kremer was arrested by Allied forces and stood trial for war crimes. During the Auschwitz Trials in Poland in 1947, Kremer was convicted of crimes against humanity, particularly for his involvement in the selection and mass murders at Auschwitz. His diary played a critical role in his conviction, as it provided concrete evidence of his participation in the Holocaust.

Kremer admitted to many of the events documented in his diary. He attempted to minimize his responsibility by claiming that he was following orders. Nevertheless, the court found him guilty, and he was sentenced to death. However, his sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment. He was released in 1958 after serving 11 years in prison.

Despite his relatively brief tenure at Auschwitz—Kremer’s actions and his written testimony make him a prominent figure in the historical record of the Holocaust. His diary remains one of the most disturbing and illuminating documents from a Nazi perpetrator, offering direct insight into the role of physicians in the Nazi killing machine.

Legacy and Reflection

The case of Dr. Johann Paul Kremer raises profound questions about the ethical responsibilities of medical professionals and the ease with which the values of medicine can be corrupted in the service of ideology. Kremer’s involvement in the Holocaust was not just a violation of medical ethics but a complete betrayal of the core humanitarian principles of medicine.

The dehumanizing language and lack of moral reflection in Kremer’s diary epitomize how Nazi ideology transformed individuals into perpetrators of mass murder. His work at Auschwitz also serves as a reminder of the dangers of pseudoscientific racial theories that fueled Nazi racial policies, leading to the systematic extermination of millions of Jews and other targeted groups.

Kremer’s diary continues to serve as a powerful testament to the moral decay that took hold within the ranks of Nazi physicians. It stands as both a warning of the capacity for human cruelty and an essential document for understanding the mindset of those who participated in the Holocaust’s machinery of death.

In the broader context of Holocaust historiography, Kremer’s story exemplifies the way in which ordinary professionals, like doctors and academics, were transformed into instruments of genocide. His life and work serve as a cautionary tale of how easily science and medicine can be perverted when detached from ethical and moral frameworks, particularly in the hands of a totalitarian regime driven by hatred and fanaticism.

He died on January 8, 1965, at the age of 81.

Diary Excerpts

September 2, 1942

“For the first time, at 3 a.m., I attended a special action. Compared to this, Dante’s Inferno seems almost a comedy. Auschwitz is justly called an extermination camp!”

September 5, 1942

“This afternoon, I was present at the 11th special action. Horrible scenes, particularly at night, when one hears the cries of those condemned to death.”

September 10, 1942

“Attended a special action at night from the F.K.L. (women’s camp): the most horrible of all horrors. Hacking through the skulls of those who were still alive.

October 18, 1942

“Today I took part in another special action, number 14 (Russians and Jews); the most horrible things I have ever seen in my life. Countless human bodies were thrown into pits, children crying and weeping, even the earth itself was crying out.”

October 29, 1942

“I had food poisoning today. For lunch, I had liver and peas; it tasted all right, but then I started feeling unwell.”

Sources

https://www.auschwitz.org/en/history/medical-experiments/johann-paul-kremer/

https://www.auschwitz.org/en/history/auschwitz-and-shoah/the-unloading-ramps-and-selections/

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/johann-paul-kremer

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11625645/

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a reply to tzipporah batami Cancel reply