Dr. Douglas McGlashan Kelley was a U.S. Army psychiatrist who became renowned for his psychological evaluations of high-ranking Nazi officials during the Nuremberg Trials. His work not only contributed to the fields of psychiatry and forensic psychology but also provided a rare glimpse into the minds of those responsible for the atrocities of the Holocaust and World War II. Kelley’s career, particularly his involvement in the postwar trials, shed light on the disturbing reality that ordinary individuals, under the right circumstances, could become perpetrators of extraordinary evil. This essay explores Kelley’s life, career, and legacy, as well as the ethical and psychological complexities of his work at Nuremberg.

Early Life and Education

Douglas M. Kelley was born on August 11, 1912, in Truckee, California. Growing up in a modest family, Kelley exhibited an early interest in human behavior and psychology. He pursued medical education at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), where he earned his medical degree. His studies coincided with significant advances in the field of psychiatry, and he became particularly interested in forensic psychiatry, a discipline that explores the intersection of mental health and law.

Kelley’s early career was shaped by his involvement in the U.S. Army during World War II. His expertise in psychiatry, combined with the military’s need for skilled mental health professionals, placed him on a path that would lead to one of the most important psychological assessments of the 20th century.

World War II and the Nuremberg Trials

At the conclusion of World War II, the Allies faced the daunting task of prosecuting high-ranking Nazi officials responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity. The International Military Tribunal (IMT) was established at Nuremberg to try 21 of these officials, who were among the architects and implementers of the Holocaust and other Nazi atrocities. These individuals included Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess, and other key figures in Adolf Hitler’s regime.

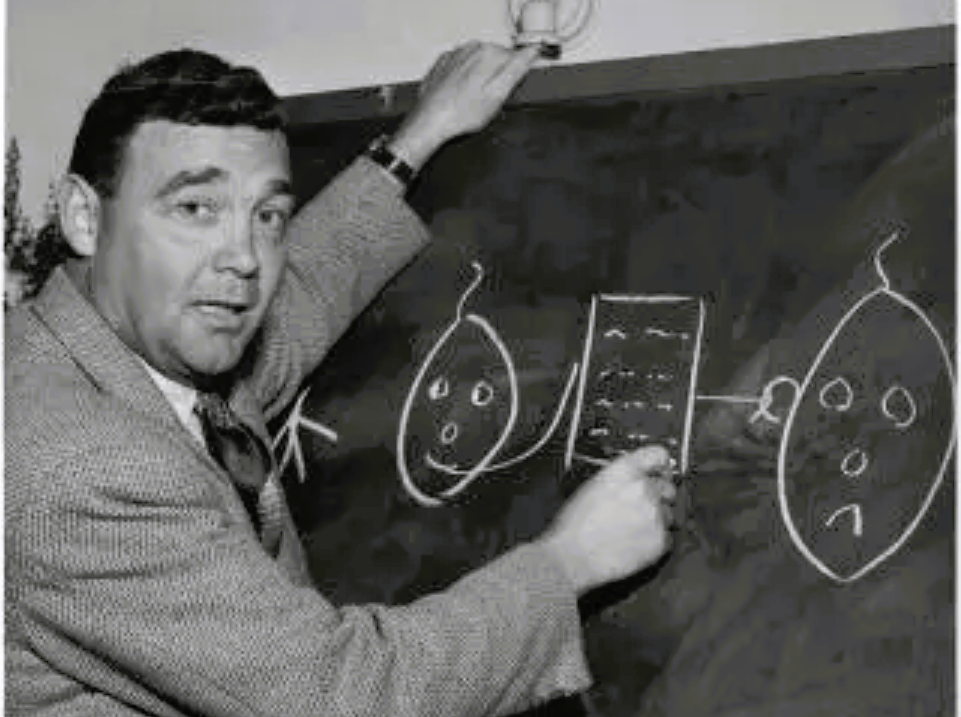

Dr. Kelley, who had risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army, was selected to be the lead psychiatrist for the American forces at Nuremberg. His task was to assess the mental health of the defendants and determine whether they were psychologically fit to stand trial. This assignment placed him at the heart of a historic moment in which justice was being sought for one of the darkest chapters in human history.

Psychological Assessments at Nuremberg

Kelley’s work at Nuremberg was groundbreaking. He employed a variety of psychological tools, including interviews, personality tests, and projective tests like the Rorschach inkblot test, to evaluate the Nazi leaders. His mission was not only to establish whether these individuals were sane but also to understand the psychological mechanisms that allowed them to participate in—and even orchestrate—the horrors of the Nazi regime.

One of Kelley’s most important and controversial findings was that the majority of the Nazi officials he examined were not “madmen” or psychopaths, as many in the public might have expected. Instead, he found that they exhibited many traits that could be found in ordinary people. These individuals were generally mentally competent and capable of logical thinking. Their participation in the Nazi regime, Kelley argued, was not the result of insanity but rather a combination of ideological conviction, conformity, and the circumstances of wartime Germany.

KEY FIGURES: HERMANN GÖRING AND RUDOLF HESS

Among the Nazi leaders Kelley evaluated, Hermann Göring, Hitler’s second-in-command and head of the Luftwaffe, was perhaps the most significant. Göring was an intelligent and charismatic figure known for his bombastic personality and sharp wit. During his imprisonment at Nuremberg, Göring continued to try to maintain control over his narrative, seeking to manipulate those around him, including Kelley.

Kelley’s interactions with Göring were both intellectually stimulating and emotionally draining. He described Göring as narcissistic, with a strong sense of self-importance, yet mentally competent and capable of understanding his crimes. Göring, who remained defiant until the end, ultimately took his own life using a cyanide capsule just hours before his scheduled execution. Kelley’s analysis of Göring raised uncomfortable questions about how individuals who are not mentally ill could still commit morally reprehensible acts on a vast scale.

Rudolf Hess, another key figure, presented a different psychological profile. Hess had been Hitler’s deputy before he famously flew to Britain in 1941 in a failed attempt to negotiate peace. At Nuremberg, Hess was erratic and exhibited signs of memory loss and paranoia. While some questioned whether Hess was feigning mental illness to avoid trial, Kelley concluded that he was indeed suffering from a psychological condition. However, it did not render him unfit to stand trial.

Kelley’s Findings: The Banality of Evil

Kelley’s evaluations of the Nazi leaders at Nuremberg led him to a disturbing conclusion: these men were not extraordinary monsters but ordinary individuals who had become part of an extraordinary system of evil. This echoed the later insights of political theorist Hannah Arendt, who famously coined the phrase “the banality of evil” during the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust. Arendt and Kelley both highlighted the idea that ordinary people, under certain circumstances, could commit horrific acts without being mentally ill or inherently malevolent.

Kelley’s findings challenged the popular notion that the perpetrators of the Holocaust and other Nazi crimes were psychologically abnormal or pathologically evil. Instead, he argued that their actions were the result of a complex interplay of personal ambition, ideological indoctrination, and social conformity within the Nazi system. This realization had profound implications for the study of human behavior, raising uncomfortable questions about the capacity for evil within all individuals.

After the Trials: Kelley’s Legacy and Struggles

After the Nuremberg Trials, Kelley returned to the United States and resumed his career in psychiatry. He wrote a book, 22 Cells in Nuremberg (1947), in which he described his experiences and the psychological profiles of the Nazi leaders he had evaluated. The book was both a clinical and personal reflection on his time at Nuremberg, offering insights into the minds of individuals responsible for unprecedented crimes against humanity.

Despite the professional success that came from his work at Nuremberg, Kelley struggled with personal demons. He had been deeply affected by his interactions with the Nazi leaders and the weight of the knowledge he had gained about human nature. These psychological burdens, combined with difficulties in his personal life, led to a downward spiral. Tragically, Kelley died by suicide in 1958, taking his own life using a cyanide capsule—a method eerily reminiscent of Hermann Göring’s own death at Nuremberg.

Ethical and Psychological Complexities

Kelley’s work raises several ethical and psychological complexities. His task at Nuremberg was to evaluate the mental health of individuals who had orchestrated or been complicit in some of the most heinous crimes in history. While his role was to provide an objective psychiatric assessment, the emotional and moral weight of his work was immense. The realization that ordinary people were capable of committing such atrocities posed profound questions about the nature of evil and the human capacity for violence.

Moreover, Kelley’s close proximity to the Nazi leaders—his daily interactions with individuals like Göring—placed him in a difficult position. He had to maintain professional detachment while grappling with the moral implications of his findings. These challenges likely contributed to his later psychological struggles and his tragic end.

Dr. Douglas M. Kelley’s work at the Nuremberg Trials remains a pivotal moment in the history of forensic psychiatry and the study of human behavior. His assessments of Nazi leaders like Hermann Göring and Rudolf Hess provided invaluable insights into the psychological profiles of those responsible for the Holocaust and other war crimes. Kelley’s conclusion that these men were not inherently insane or psychopathic but rather ordinary individuals shaped by extraordinary circumstances forced the world to confront the unsettling reality of human nature.

While Kelley’s professional achievements were significant, his personal struggles and tragic death underscore the psychological toll that such work can take. His legacy, however, endures as a reminder of the complexities of evil, the dangers of conformity, and the ethical challenges faced by those who seek to understand the darkest aspects of human behavior. Kelley’s life and work continue to influence the fields of psychology, law, and history, offering essential lessons about the human capacity for both good and evil.

Sources

https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Mysterious-suicide-of-Nuremburg-psychiatrist-2732801.php

https://perspectives.ushmm.org/item/manuscript-of-douglas-m-kelley

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-25774-000

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment