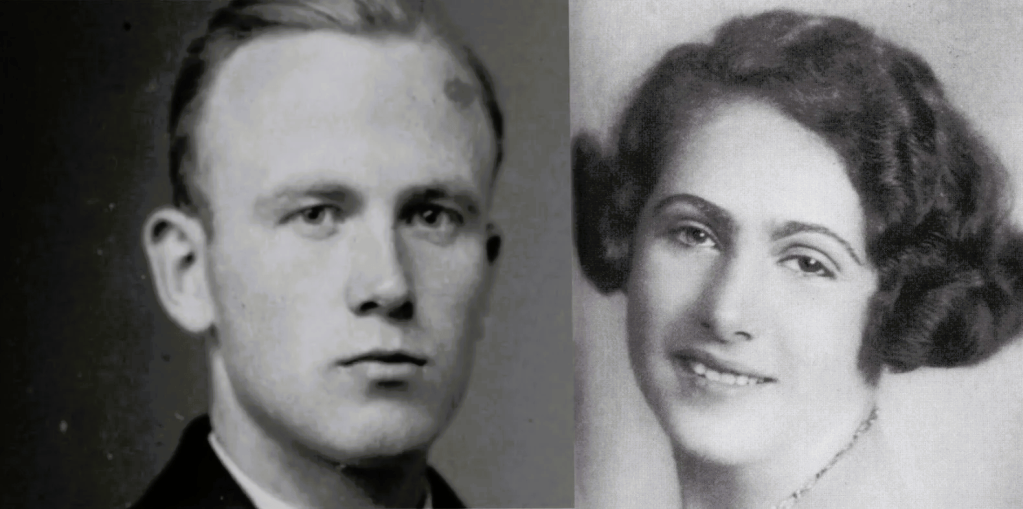

This is the remarkable story of Edith Hahn Beer (Vienna, January 24, 1914 – London, March 17, 2009), an Austrian Jewish woman who survived the Holocaust by adopting a false identity and marrying a member of the Nazi Party (NSDAP). Her incredible tale of survival serves as a testament to human resilience and the complexity of morality, showing that even those who initially choose a misguided path are capable of acts of goodness.

Early Life and Education

Edith Hahn was born into an assimilated Jewish family as one of three children. Her parents, Clotilde and Leopold Hahn, owned a restaurant in Vienna where the family often gathered. The restaurant was not kosher, reflecting her parents’ non-orthodox lifestyle, as they rarely attended synagogue. Edith grew up as a happy and intelligent child, excelling academically. Her schoolteacher convinced her father to send her to higher education—a rare opportunity for girls at the time.

During her school years, Edith fell in love with Joseph “Pepi” Rosenfeld, the son of a Jewish father and a Catholic mother. They bonded over shared intellectual pursuits, discussing politics, philosophy, socialism, and dreams of a better world. At that time, Vienna had a strong socialist presence, which also influenced Edith. Adolf Hitler was not yet a prominent topic of discussion in Austria, as Nazism in Germany seemed distant. Edith dismissed Hitler as a bombastic speaker, lacking depth.

Though she was primarily interested in philosophy, Edith enrolled at the University of Vienna in 1933 to study law. She aspired to become a lawyer or judge and fight for justice.

The Anschluss

In 1938, Nazi Germany (the Anschluss) annexed Austria. This event abruptly ended Edith’s studies. Just before her final exams, which would have earned her a doctorate, she was aware that, as a Jew, she would no longer be allowed to graduate.

Anti-Semitism in Austria escalated rapidly, becoming even more virulent than in Germany. Edith, like many other Jews, sought to flee the country. However, her beloved Pepi refused to leave, as his Catholic mother threatened to take her own life if he did. Edith stayed behind for Pepi’s sake. Her two sisters managed to escape to Palestine on the night of Kristallnacht. Meanwhile, Pepi’s mother pressured him to sever ties with Edith. On that same night, Edith was forced to say goodbye to him.

Forced Labor

Edith and her mother were ordered by the Gestapo to move to a cramped room in the Vienna ghetto, sharing it with five others. The Nazis meticulously registered Jews, and in 1941, Edith and her mother were summoned to a registration center. While waiting in line, the Gestapo selected them for transport to a forced labor camp in Osterburg, northern Germany. Edith pleaded for her mother to be spared due to her age, and her request was granted. However, Edith herself was sent to the camp, where she endured over a year of harsh labor. She never saw her mother again.

—Edith, about forced labor in a paper factory in Aschersleben labour camp, Germany, 1941:

“The skin on my fingertips wore through, rubbed to a bloody mess by the cardboard. I would have been to use gloves, but you couldn’t run the machine wearing gloves; they slowed you down and increased the likelihood that your fingers would be chopped off. So I just bled”.

After returning to Vienna in June 1942, Edith learned that her mother had been deported to Poland two weeks earlier. Determined to avoid the same fate, Edith tore the Jewish star from her clothing and decided to go into hiding. Desperate, she sought help from Maria Niederall, a Nazi Party member who had been known to assist Jews.

—Edith about Maria Niederall, her Nazi friend, Vienna, 1942:

“Maria took my hands in hers. “You have to soften up these hands,” she said and rubbed sweet-smelling lotion into my cracked and calloused palms. The feel of her strong fingers on my wrist, the smell of the cream–it was such an urbane comfort, so civilized. “Take this cream with you. Put it on your hands every day, twice a day. You’ll soon feel like a woman again.”

Maria directed Edith to an SS officer, who surprisingly offered help. He advised Edith to acquire false identity papers, a task she accomplished with the help of her Christian friend, Christl Margarethe Denner. From that point on, Edith lived as “Margarethe (Grete) Denner.”

Munich and Marriage

With her forged Aryan papers, Edith moved to Munich in August 1942 and began working for the Red Cross. Shortly after, she met Werner Vetter, an artist and NSDAP member who painted aircraft for the Luftwaffe. Werner fell in love with “Grete” and proposed marriage. Recognizing the risks of marrying a Nazi Party member, Edith revealed her true identity and her forged papers. To her astonishment, Werner accepted her past and promised to keep her secret—a promise he kept throughout his life.

The couple married on October 16, 1943, and Edith gave birth to their daughter, Maria Angelika, on April 9, 1944. Their child was likely the only Jewish baby born in a Nazi hospital. In September 1944, Werner was conscripted to fight on the Eastern Front, where he was captured by Russian forces and sent to a Siberian prison camp.

After the War

Edith’s home in Brandenburg was destroyed in Allied bombings, but amidst the rubble, she recovered her original passport and university documents, which she had hidden in a suitcase. She resumed her identity as “Edith Vetter, née Hahn” and sought news of her mother at a Berlin transit camp for Jewish survivors. However, other Jewish survivors met her with hostility, resenting her seemingly unscathed appearance.

Offered a position as a judge by the Communists in Brandenburg, Edith eagerly accepted. In an unexpected twist, Werner returned alive two years after the war. Despite her love for him, their relationship faltered. Edith, now an independent woman with a career, no longer fits Werner’s expectations of a traditional wife. Their marriage ended in divorce, and Werner died in Germany in 2002.

Disillusioned with the strict Communist regime in East Germany, Edith moved to London to join her sister.

Later Life

In 1957, Edith married Fred Beer, a Viennese Jew living in London who, like her, had survived the Holocaust. After his death, she emigrated to Israel but eventually returned to London, where she spent her final years in a nursing home.

In 1999, her English-language autobiography was published, followed by a German edition in 2000 titled Ich ging durchs Feuer und brannte nicht (I Walked Through the Fire and Was Not Burned). In Dutch, the book was published as De joodse bruid (The Jewish Bride). In 2002, her story was adapted into a documentary directed by Liz Garbus.

Sources

https://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/people/highlights/edith.shtml

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edith_Hahn_Beer

https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/not-a-good-time-for-love-11-love-stories-of-the-holocaust-survivors/

https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn506448

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Books-Edith-Hahn-Beer/s?rh=n%3A266239%2Cp_27%3AEdith%2BHahn-Beer

https://knihobot.cz/g/587878/b/9911524?fallbackStrategy=state

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donations

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment