Adolf Eichmann, one of the chief architects of the Holocaust, is infamous for his role in orchestrating the mass deportation of Jews to Nazi extermination camps. However, among his numerous atrocities, one of the most controversial and perplexing episodes was the so-called “Blood for Goods” deal. This proposal, made during the final years of World War II, reflected the desperation of the Nazi regime and its paradoxical approach to genocide and diplomacy.

The Origins of the Deal

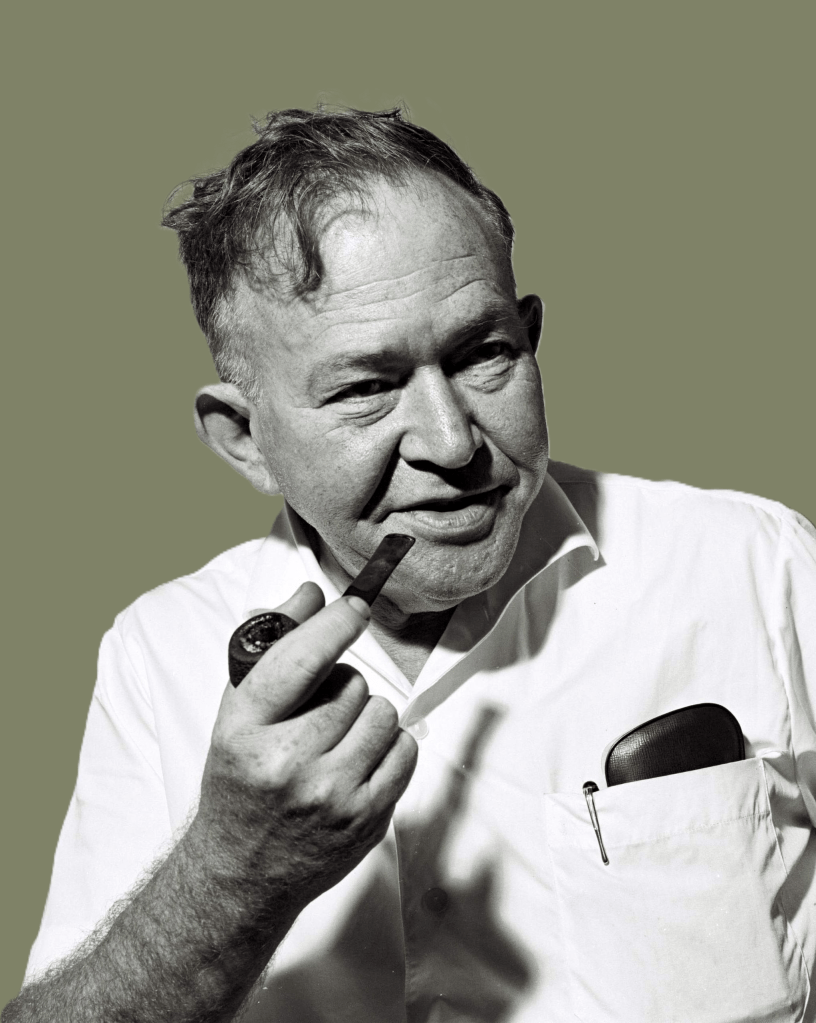

On April 25, 1944, at the Hotel Majestic in Budapest, Adolf Eichmann met with Joel Brand, a key member of the Jewish Relief and Rescue Committee. Brand had previously engaged in negotiations with Eichmann and other SS officers, attempting to bribe them in exchange for allowing Jews to escape Hungary. During this meeting, Eichmann made a shocking proposition: “I am prepared to sell one million Jews to you.”

By 1944, the tide of World War II had turned against Nazi Germany. The Allied forces were advancing on both the Western and Eastern fronts, and the Axis powers were losing ground. At the same time, the Nazi leadership continued its relentless pursuit of the “Final Solution”—the extermination of European Jews. Eichmann, operating under Heinrich Himmler’s directives, sought to exploit Jewish lives as a bargaining chip for military and economic gains.

The “Blood for Goods” deal was proposed by Eichmann to Joel Brand, a Hungarian Jew and member of the Aid and Rescue Committee, a Jewish relief organization.

The idea was simple yet horrifying: the Nazis would exchange one million Jews, primarily from Hungary, for 10,000 trucks and other supplies that would be used exclusively on the Eastern Front against the Soviet Union. The proposed trade suggested that the trucks would not be used in the war against the Western Allies, an attempt to make the deal more palatable to Britain and the United States.

International Reactions and Consequences

Brand was sent to Istanbul to negotiate with the Western Allies, particularly Britain and the United States. However, the proposal was met with deep suspicion. The Allies viewed it as a cynical ploy, either as an attempt to create divisions among them or as a desperate Nazi effort to stave off inevitable defeat. Additionally, Britain feared that allowing Jewish refugees to enter Palestine (then under British control) would destabilize the region.

The British authorities arrested Brand upon his arrival in the Middle East, suspecting that he was being used as a Nazi pawn. The deal ultimately collapsed, and no trucks were delivered. Meanwhile, the extermination of Hungarian Jews continued unabated. Over 400,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz within months, most of them perishing in gas chambers.

This was not the end of the story. Rudolf Kasztner , was a Hungarian-Jewish journalist, lawyer, became Eichmann’s primary contact after Eichmann sent Joel Brand to Istanbul to negotiate with Jewish leaders abroad.

According to Eichmann, Kasztner, whom he described as a “fanatical Zionist,” agreed to discourage Jewish resistance to deportations and maintain order in the collection camps. In return, Eichmann claimed he allowed a limited number of young Jews to emigrate illegally to Palestine. “It was a good bargain,” Eichmann later stated. “For keeping order in the camps, the price of 15,000 to 20,000 Jews—in the end, perhaps more—was not too high for me.”

Between August 21, 1944, and April 1945, Kasztner traveled to Germany multiple times and visited Switzerland five times. He met with representatives of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the Jewish Agency to secure funding for rescue efforts. As a result of these negotiations, the Germans allowed the transfer of two groups of Jewish prisoners—318 on August 18 and 1,368 on December 6, 1944—from Bergen-Belsen to Switzerland. Most were of Hungarian and Transylvanian origin. Kasztner’s discussions with the Germans were also aimed at ensuring the survival of Jews in the Budapest ghetto.

After the war, while living in Israel, Kasztner was accused of collaborating with the Nazis. A defamation trial initially ruled against him, but he was later partially exonerated. In 1957, he was assassinated in Tel Aviv by right-wing extremists. His legacy remains debated, with some viewing him as a hero and others as a controversial figure.

Eichmann’s Role and Motivations

Eichmann’s involvement in the “Blood for Goods” deal remains a subject of debate. On the surface, he appeared to act as an intermediary, executing orders from Himmler, who was beginning to explore separate peace negotiations with the Western Allies. However, Eichmann’s personal commitment to genocide remained unwavering. Even when negotiations were taking place, he ensured that deportations from Hungary continued at an unprecedented pace. His actions suggest that he either doubted the deal’s viability or simply viewed it as a ruse to delay potential interventions while exterminations proceeded.

The Aftermath and Historical Significance

The failure of the “Blood for Goods” deal underscored the extent of the Nazi leadership’s desperation and the moral complexities faced by the Allies. From a humanitarian perspective, the Western powers have been criticized for not engaging more earnestly in negotiations that might have saved lives. Some historians argue that even a partial agreement could have slowed the Nazi killing machine, while others contend that any cooperation with the Nazis would have been futile and ethically compromised.

Eichmann was later captured by Israeli agents in Argentina and put on trial in Jerusalem in 1961. His role in the Holocaust, including the “Blood for Goods” affair, was extensively scrutinized. He was found guilty of crimes against humanity and executed in 1962.

Eichmann’s “Blood for Goods” deal remains one of the most chilling examples of Nazi cynicism—placing a literal price on human lives while continuing mass murder. It represents the brutal pragmatism of a regime that, even in its dying days, sought to manipulate and deceive rather than show remorse. The episode stands as a tragic reminder of the world’s failure to act decisively in the face of genocide and raises enduring ethical questions about wartime diplomacy and humanitarian intervention.

sources

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%206081.pdf

https://www.holocausthistoricalsociety.org.uk/contents/naziseasternempire/joelbrand.html

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-quot-blood-for-goods-quot-deal-april-1944

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joel_Brand

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rezs%C5%91_Kasztner

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment