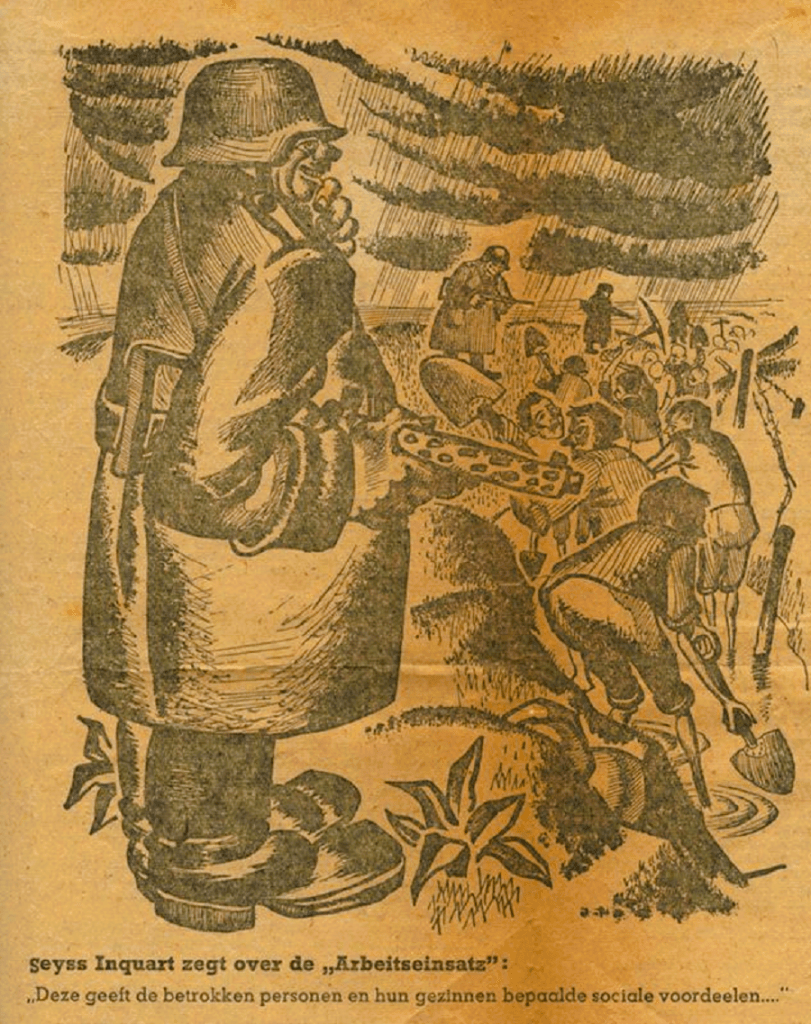

The Arbeidsinzet (labor deployment) is the term for the forced employment of the Netherlands. It is estimated that over half a million Dutch people worked in Germany (and German-occupied territories) during the war. Some went voluntarily, but most were forced against their will.

The forced labor deployment of Dutch people in Germany happened in different phases, gradually affecting more and more people. Before the war, unemployed individuals were already being sent to Germany, and refusal could, in some cases, result in the withdrawal of unemployment benefits or at least the threat of it. This practice was significantly expanded from June 1940 onward. Between the summer of 1940 and the spring of 1942, thousands of workers, in addition to the unemployed, voluntarily left for Germany. They were lured by propaganda campaigns that promised attractive working conditions and high wages.

To organize labor placement efficiently, the Rijksarbeidsbureau (National Employment Bureau) was established in September 1940. This new institution consisted of 37 regional employment offices and 143 branch offices. They were responsible for sending workers to Germany and operated under strict control of the occupying forces. The Hauptabteilung Soziale Verwaltung, a division of the Generalkommissariat für Finanz und Wirtschaft, oversaw the functioning of this new government body.

Due to the increasing demand from Germany for workers to support the war economy, the obligation to work was expanded on March 23, 1942. Under the orders of Fritz Sauckel, the German-appointed Generalbevollmächtigter für den Arbeitseinsatz (General Plenipotentiary for Labor Deployment), several actions and decrees were issued to obtain the necessary workforce. The so-called “Sauckel actions” involved selectively searching Dutch companies for needed workers. German commissions carried out inspections, selecting men to be sent to Germany. Their names were then forwarded to local Dutch employment offices, which were responsible for calling up the workers, conducting medical examinations, and arranging their departure. Workers were especially taken from companies that did not contribute to the German war industry. Moreover, the Germans preferred to send unmarried and/or childless men rather than workers with families.

The Sauckel actions had mixed success and did not yield the desired results. The German war industry became increasingly dependent on workers from occupied territories, especially as more German soldiers were deployed to the Eastern Front in the Soviet Union. Because of this, German laborers were withdrawn from production to serve in the military. As a result, the demand for workers increased between May 1943 and September 1944, a period characterized as “intensified labor deployment.”

On May 6, 1943, the occupiers issued a decree requiring all men aged 18 to 35 to report to an employment office. Certain professions were exempt from this requirement. However, young men born between 1920 and 1924 were specifically ordered to report for labor deployment. This became known as the “year-group action” (jaarklassenactie). Only a relatively small number of young men from these birth years actually went to Germany. Many were still granted exemptions, while others went into hiding to avoid deployment.

In addition to calling up young men, on April 29, 1943, the Wehrmachtbefehlshaber in den Niederlanden (German Military Commander in the Netherlands) announced that former Dutch soldiers would once again be taken as prisoners of war. Fearing a possible Allied invasion, the Germans worried that Dutch soldiers might join the resistance. A secondary advantage of detaining these former soldiers was that they could also be forced into labor in Germany.

The period from September 1944 until liberation was known as the “total labor deployment” (totale arbeidsinzet). During this phase, large-scale raids (razzias) were conducted to round up men en masse. One of the largest raids, the Rotterdam raid, resulted in over 50,000 men being captured and ultimately deported to Germany. Previously granted exemptions often became worthless during this stage.

The forced employment of mainly young men sparked significant resistance in Dutch society. Some who received a summons went into hiding, though finding safe places was not always easy. Additionally, because they were in hiding, they could no longer collect their food ration cards, making them dependent on others for survival. Some Dutch civil servants working in employment offices also resisted by deliberately falsifying, misplacing, or destroying administrative records to help people avoid forced labor.

One of the 500,000 was Antoon Gerrit Guillaume van Hilten aka Tom van Hilten

On November 9, 1923, Antoon Gerrit Guillaume van Hilten was born in Geleen

In the early morning of May 10, 1940, German troops invaded the Netherlands. There were bombings on military targets such as the naval base in Den Helder and the airfield in Bergen. Thousands of evacuees fled to towns and villages in North Holland. Because the Afsluitdijk held out for a long time, it was only after the capitulation that German ground troops appeared in North Holland. At that time, Antoon Gerrit Guillaume was 16 years old and living in Amsterdam

He was a student and an office clerk.

He had evaded forced labor in Germany but was caught during a razzia in 1942 or 1943 and deported to Germany.

The municipality of Geleen wrote to the OGS(War Graves Foundation): ‘However, he went into hiding and was later arrested by the “Landwacht.” After being imprisoned in the cells in Amsterdam, he was sent via the “Amersfoort” camp to the Neuengamme concentration camp, where he died on February 24, 1945.’

The Landwacht was an auxiliary police force made up of Dutch national-socialists.

His name is inscribed on the war memorial in Geleen-Lindenheuvel

sources

https://www.oorlogsbronnen.nl/tijdlijn/8ef425eb-a87c-42f8-875a-a4088f3c9927

https://oorlogsgravenstichting.nl/personen/63846/antoon-gerrit-guillaume-van-hilten

https://database.documentatiegroep40-45.nl/details2.php?ID=7735

https://www.niod.nl/zoekgidsen/arbeidsinzet-1940-1945

https://www.nationaalarchief.nl/onderzoeken/zoekhulpen/arbeidsinzet-1940-1945

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment