he Murder of Robert Einstein’s Family: Tragedy, Trauma, and the Aftermath

The horrors of World War II left few untouched, but among the lesser-known and profoundly personal tragedies of the conflict was the brutal murder of the family of Robert Einstein, cousin of the famed physicist Albert Einstein. This grim event took place on August 3, 1944, in the hills of Tuscany, Italy, and continues to resonate as an emblem of the human cost of war, the fragility of justice, and the enduring scars of trauma.

Background: Who Was Robert Einstein?

Robert and Albert grew up together in Munich, Germany, during the 1880s and 1890s. For eleven years, they even lived under the same roof. More than just cousins, they were like brothers—“brother-cousins,” you might say. Their fathers, Jakob and Hermann Einstein, were business partners who ran an electrification company. Together, they brought electric light to beer halls, town squares, and cafés across the region.

In 1894, their fortunes took a turn when the Einstein company lost out on a major contract and went bankrupt. The families relocated to Milan, determined to start anew. But when this second venture also failed, the business partnership dissolved. Still, the bond between Robert and Albert endured.

Robert remained in Italy, became a qualified engineer, and married Nina Mazzetti, the daughter of a northern Italian priest. In the 1920s, the couple settled into a modest apartment in Rome, where they began to build a new life together.

Around this time, Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party (PNF) rose to power in Italy. In the early years, the fascists were not overtly antisemitic; Jewish Italians were just as likely to join the party as anyone else. Robert Einstein, though Jewish himself, chose not to become a member. Still, as a businessman, he was sympathetic to the regime’s investments in public infrastructure and its push to modernize the state.

Meanwhile, Albert Einstein had returned to Germany and was making groundbreaking strides in theoretical physics. In 1922, he was awarded the Nobel Prize, cementing his status as the most famous scientist in the world.

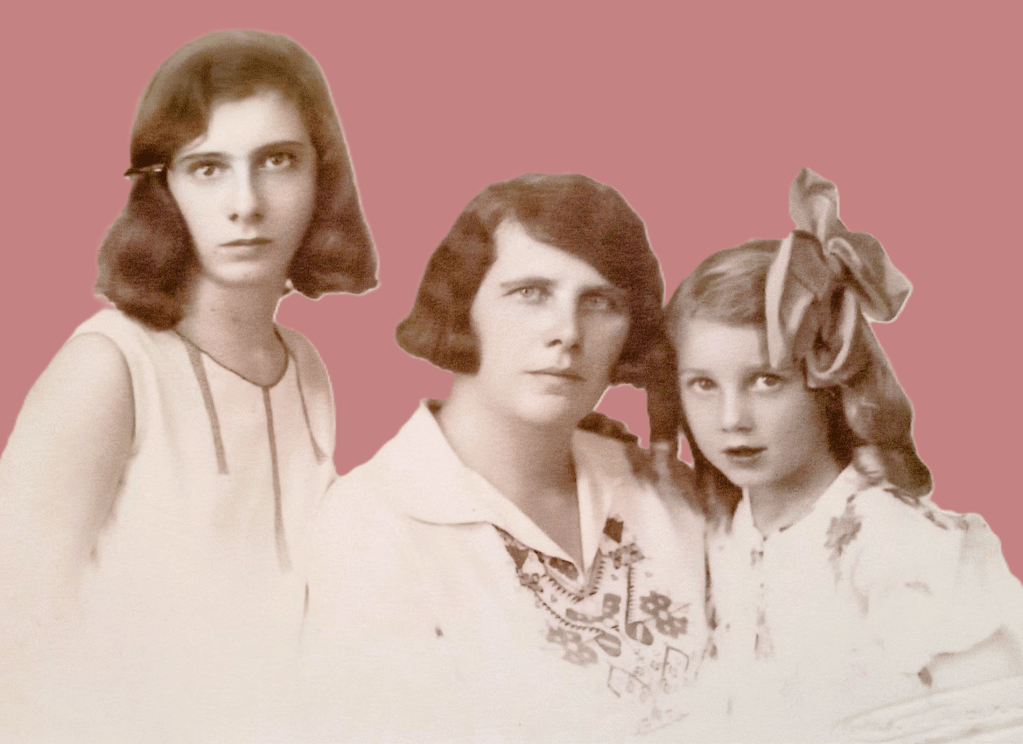

By 1934, Robert and Nina Einstein were still living in Rome when Nina’s brother came to them in need. His wife had passed away, and he was struggling to care for their seven-year-old twin daughters. Though Robert and Nina already had two daughters of their own—Luce, aged seventeen, and Cici, eight—they didn’t hesitate to take in their nieces.

With four children under one roof, their Roman apartment quickly felt too cramped. Sharing a deep love for nature, Robert and Nina decided it was time for a change. They set their sights on the countryside and eventually found a villa just outside Florence, called Il Focardo. Surrounded by peach orchards, olive groves, and rows of vines, the estate felt like a dream. Even better, it came with ten contadini—tenant farmers who would help manage the land. It was, in every sense, a little slice of paradise

On 11 November 1938, to the shock of Italian Jews, Benito Mussolini announced the introduction of racial laws modeled after Nazi Germany’s Nuremberg Laws. Parliament quickly approved the legislation, and it was signed into law by King Vittorio Emanuele III. Under the new regulations, Jewish children were barred from attending public schools and universities. Jews were prohibited from working in banks, insurance companies, or local government. They could not marry non-Jews, serve in the military, or remain members of the National Fascist Party.

In practice, enforcement of these laws varied widely, depending on the attitudes of local police and party officials. For the Einsteins at Il Focardo, life remained relatively undisturbed. Luce continued her studies at medical school in Florence, while Cici and her cousins attended the local high school. Robert and Nina focused on running the estate, largely insulated from the harsher realities unfolding elsewhere.

That fragile sense of normalcy was shattered in the autumn of 1943, when the German army swept into northern Italy and occupied Florence and its surrounding areas. On 1 December, Mussolini’s Minister of the Interior, Guido Buffarini Guidi, announced Police Order Number 5 on national radio. Its message was chilling: all Jews were to be arrested and sent to concentration camps.

Over the next seven months, more than 8,000 Jews—approximately 20% of Italy’s Jewish population—were rounded up in a wave of mass arrests known as the razzia. These operations were carried out by German SS and police units, often with the support of Italian fascist collaborators

Robert and Nina remained at Il Focardo with their two daughters and two nieces. They were soon joined by Nina’s sister, Seba, and a third niece, Anna Maria—the daughter of another of Nina’s sisters, whose family had hoped she would be safer in the countryside.

In the days and weeks that followed, the family watched with mounting dread as Jews across Tuscany were arrested and deported. Trains bound for Auschwitz became a haunting symbol of the horrors unfolding just beyond their quiet estate.

By then, it was too late for the Einsteins to flee. The borders were sealed tight. Railway stations, airports, and mountain passes were heavily guarded. With escape routes cut off and the net tightening, the family had no choice but to stay—and to hope

Despite the growing danger, the Einsteins still believed they were safe. Il Focardo was secluded, nestled deep in the countryside and far from the main roads and watchful eyes. Nina and the other women in the family were Christian and, under the racial laws, not considered targets of the roundups. And while Robert was Jewish, he was an Italian citizen—well-respected in the local community and known more as a neighbor and benefactor than as a political threat. It seemed unthinkable that anyone would betray him.

.

The Murder

In the summer of 1944, as Allied forces pushed north through Italy, German troops were retreating through Tuscany. On August 3, a group of German SS soldiers arrived at the Einstein villa. Robert, fearing for his safety due to his Jewish heritage and well-known surname, had fled to hide with locals in the forest, hoping to protect his family by keeping himself away.

Despite his absence, the soldiers detained his wife Cesarina and his daughters. They searched the house, interrogated the women, and inexplicably concluded—likely due to their association with Robert and possibly Albert Einstein—that they posed a threat or were worthy of punishment. Without trial or cause, the SS troops executed all three women by shooting them in the garden of their home and set the house ablaze.

Aftermath: Trauma and Questions

Einstein returned to Il Focardo when he saw the smoke rising from the villa—though some accounts claim he didn’t arrive until the following day. What he found was devastating. His wife and daughters had been murdered. In despair, he attempted to take his own life, but survived.

Soon after, British troops arrived in the area. Grieving and desperate for justice, Robert Einstein used his famous surname to call for an investigation into the killings. A few days later, a scrap of paper surfaced, claiming that the family had been executed because they were Jewish (though they were not) and suspected of espionage.At almost the same moment that Robert Einstein heard the rattle of machine-gun fire at Il Focardo, German forces in Florence were destroying five of the city’s bridges across the Arno River. Shortly after, they began their retreat to the north.

By early the next morning, on 4 August 1944, New Zealand soldiers entered Florence. The city was liberated.

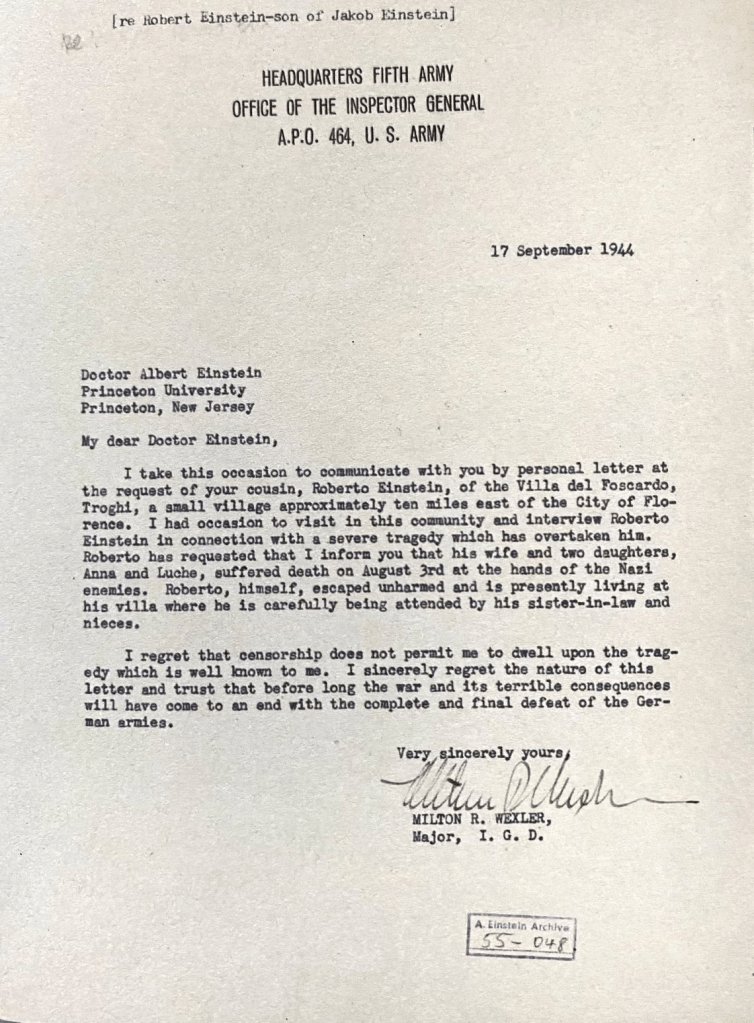

Six weeks later, a letter arrived for Albert Einstein from an American war crimes investigator. It carried devastating news: his cousin’s family had been murdered in Italy. The loss, compounded by the horrors unfolding across Europe, struck Albert deeply.

Determined to uncover the truth, Robert pushed for an official inquiry, even reaching out to his cousin Albert for help. The incident was documented in an Army Judge Advocate General (JAG) report, though the full extent of justice remained elusive.

On July 13, 1945—his 32nd wedding anniversary—Robert Einstein took his own life by overdosing on sleeping pills. He was laid to rest beside his wife and daughters in the cemetery at Badiuzza.

His nieces, Lorenza and Paola Mazzetti, survived the war. Their story was later revisited in a 2016 German documentary, honoring both their survival and the family they lost.

Pursuit of Justice

For decades, the murders remained largely unacknowledged in the broader tapestry of WWII war crimes. Italy’s post-war turmoil, the destruction of records, and the Cold War climate often hindered systematic efforts to investigate such atrocities. In 2007, German authorities reopened the case, largely thanks to persistent journalistic and scholarly efforts. Despite identifying some of the perpetrators, legal obstacles—including the advanced age of suspects and insufficient evidence—prevented full prosecution.

This lack of justice reflects a broader pattern in post-war Europe, where many lower-level war crimes remained unpunished. It also illustrates the moral complexity and limitations of retrospective justice when crimes occur in the chaos of wartime.

Moreover, this tragedy resonates in contemporary conversations about memory and accountability. It compels societies to confront the personal dimensions of historical trauma, to honor the victims not just in numbers but by name and story, and to recognize the long shadows that such events cast over generations.

sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murder_of_the_family_of_Robert_Einstein

https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/robert-einsteins-suicide/

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment