s Allied forces closed in on Germany in early 1945, the SS began evacuating inmates from camps like Dachau in a series of forced marches, hoping to hide evidence of atrocities and prevent liberation by the Allies. Prisoners, already debilitated by starvation and disease, were forced to march dozens of miles in the brutal cold with little to no food or shelter. Those who fell behind were often executed on the spot.

In April 1945, one such death march—carrying prisoners from Dachau toward the Austrian border—was intercepted by the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion in southern Bavaria. What they encountered was harrowing: hundreds of skeletal prisoners, many wearing the telltale striped uniforms of concentration camps, wandering aimlessly or lying in ditches, barely clinging to life. Some had been shot; others were dying of exhaustion, exposure, or disease. Without knowing precisely what they had come upon, the men of the 522nd sprang into action, providing emergency aid, food, and care to the survivors. In doing so, they saved hundreds from certain death.

The Nisei 522nd Field Artillery Battalion was part of one of the most decorated military units in American history: the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. This unit was composed of Japanese American men who volunteered for service, many from Hawaii and others from internment camps across the United States. The 442nd was a segregated regiment that, despite its members’ American citizenship, operated under a cloud of suspicion due to their Japanese ancestry.

Although their parents were immigrants from Japan, these soldiers were born in the United States. They identified as Nisei, meaning “second generation.” With an average IQ of 116—high enough to qualify many of them for officer training—they demonstrated exceptional intelligence and dedication. Above all, they were deeply committed to their families, their communities, and their country. Their battle cry, Go For Broke!, captured their spirit and determination—it meant “give it your all.”

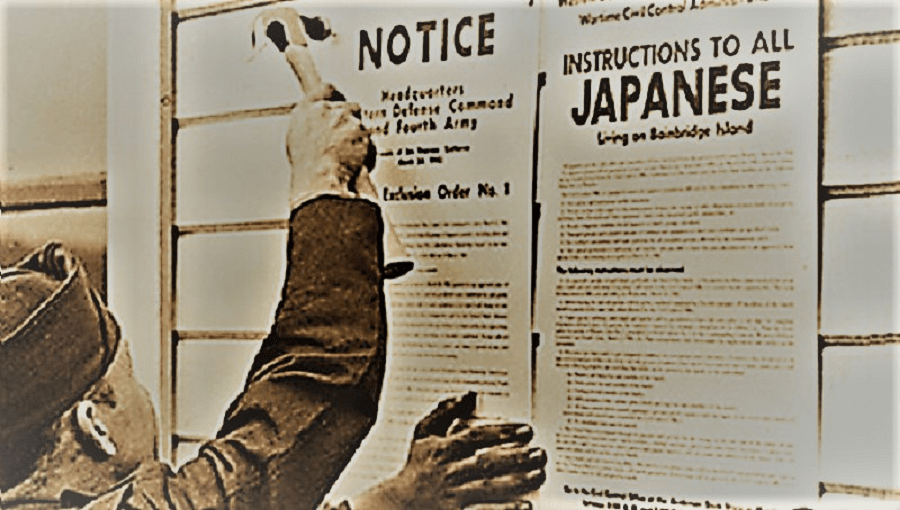

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. In doing so, he authorized the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast without due process, violating fundamental principles of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. This unprecedented action cast Japanese Americans as disloyal, simply because of their ancestry.

Under the pretense of “military necessity,” all Japanese Americans living within 500 miles of the West Coast were ordered to leave their homes and property. The impact on the community was devastating—physically, financially, and emotionally.

More than 120,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly interned for the duration of World War II. With only a few days to prepare, they were allowed to bring just two bags each. Families lost homes, businesses, farms, vehicles, furniture, and possessions accumulated over a lifetime.

There was no evidence of disloyalty among Japanese Americans. In fact, both FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and U.S. Naval intelligence advised against the internment. Despite this, Japanese Americans were told the action was “for their own protection.”

Ten internment camps were constructed in remote deserts, mountains, and plains across the American West. Surrounded by barbed wire, guarded towers, and armed soldiers, the camps stripped away basic freedoms. Life inside was harsh and demoralizing. Families lived in long rows of black tar-paper barracks, which lacked insulation and provided little protection from freezing winters or relentless dust storms. Traditional family roles and community structures were disrupted and weakened.

Remarkably, many Japanese Americans still chose to serve their country. Some volunteered, while others were drafted—many directly from the camps. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team, one of the most decorated units in U.S. military history, included Nisei soldiers from both the mainland and Hawaii.

Those from Hawaii came from a range of backgrounds—some from urban Honolulu, others from rural pineapple and sugar cane plantations. For many, the war marked their first time leaving the islands, and in some cases, the United States itself.

Several Caucasian officers serving in the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion were Jewish, including Captain Charles Feibelman. Having fled Europe in the 1930s, Captain Feibelman studied law in the United States. Tragically, several members of his family were murdered at Auschwitz.

As a forward observer, Captain Feibelman was among the first American soldiers to encounter Jewish survivors of the Dachau death march near Waakirchen, Germany. He was accompanied by several Nisei soldiers, including Sergeant Joe Obayashi. Observing the scene, Captain Feibelman remarked to one of the Nisei, “We must be among the first to get here.” Before them, a large group of emaciated prisoners in striped uniforms wandered through an open snow-covered field.

Although the Nisei troops were under strict orders not to share rations, many felt compelled to defy those orders. Sergeant Imamura later recalled, “We had been ordered not to give rations to the Dachau prisoners because the war was still on and supplies were needed for our own troops—but we gave them food, clothing, and medical supplies anyway. The officers looked the other way. These prisoners were sick, starving, and dying. They needed help, and they needed it immediately.”

He added, “I saw one GI throw orange peels into a garbage can. A prisoner grabbed the peelings, tore them into small pieces, and shared them with the others. They hadn’t had fruit or vegetables in months. They had scurvy. Their teeth were falling out.”

PFC Hideo Nakamine remembered, “It was terrible. We were ordered not to give away our rations, but we disobeyed—those people were starving to death. The suffering was horrible.”

Some Nisei soldiers were able to communicate directly with the prisoners. Mike Hara of Headquarters Battery recounted a conversation with an inmate who said he had been imprisoned for his political beliefs. “He told me he hated Hitler and everything he stood for. I shared some army rations with him.”

PFC Roy Okubo of B Battery recalled, “A little old bearded man came up to me, grinning from ear to ear. I think he was just happy to be alive. I believe he was Jewish, but I’m not sure. I gave him a cigar. He offered to wash dishes in exchange for food.”

Many Nisei soldiers said they were never the same after witnessing the aftermath of the death march. PFC Neil Nagareda has spent the past fifty years wondering “how people could be that cruel to other human beings.” The experience left an indelible mark on their lives. It is believed that the Nisei soldiers of the 522nd were among the first Allied troops to reach and liberate the survivors of the Dachau death march on the morning of May 2, 1945.

Some officers ordered their men not to speak about what they had seen. Many Nisei veterans never shared their experiences, even with their families. The memories remained a heavy burden, one that caused deep and lasting anguish.

Dachau concentration camp inmates on a death march, photographed on 28 April 1945 by Benno Gantner from his balcony in Percha.[1] The prisoners were heading in the direction of Wolfratshausen.

The 522nd Field Artillery Liberates the Landsberg-Kaufering Dachau Death March

May 2, 1945

Near the end of World War II, sub-camps of the Dachau concentration camp complex were established around the towns of Landsberg and Kaufering, in Bavaria, Germany. These eleven camps, opened in the spring of 1944, were exclusively for Jewish slave laborers. Their horrific purpose was to build vast underground factories to assemble the ME 262, the world’s first operational jet fighter, for the German Luftwaffe.

The conditions in the Landsberg-Kaufering camps were lethally brutal. In just one year, tens of thousands of Jews were worked to death. The average prisoner survived less than four months. These sub-camps claimed more lives in one year than the main Dachau camp did in over thirteen.

The laborers—men and women from Hungary, Poland, and Lithuania—numbered over 30,000. Fewer than 15,000 were still alive by the time the camps were evacuated.

In the final days of April 1945, as Allied forces closed in, Hitler and Himmler ordered the forced evacuation of the surviving prisoners. Their aim was to use them to build last-ditch fortifications near the Bavarian-Austrian border—or to simply murder them before liberation. On April 24, more than 10,000 Jews were forced onto what would become one of the war’s most infamous death marches. Those too weak to walk were immediately executed.

From April 26, prisoners from the outer sub-camps were herded into the main Dachau camp, then driven south on foot. The SS and their Ukrainian and Hungarian collaborators showed no mercy. The marchers, already near death, were given no food or water. Anyone who fell was shot or torn apart by guard dogs. In just five days, over half the prisoners were dead.

The march was a nightmare of cruelty and starvation. Survivors, some weighing under 80 pounds and dressed only in tattered uniforms and wooden clogs, staggered through Bavarian towns. German civilians who once claimed ignorance of Nazi atrocities now witnessed their undeniable reality.

Zwi Katz, a young Lithuanian Jew, recalled:

“Our German and Ukrainian guards were unbelievably cruel. If you couldn’t walk, they shot you in the head and left your body in the road.”

Another survivor, Solly Ganor, just twelve years old when the Holocaust began in Lithuania, recounted his experience:

“We marched for over five days. It rained and snowed. We were starving and exhausted. I saw many people murdered right in front of me. I don’t know how I survived—I just kept putting one foot in front of the other.”

By May 1, the march had reached the outskirts of Bad Tölz. Fewer than 6,000 Jews remained alive. A late-season snowfall blanketed the Bavarian countryside. On the evening of May 2, near the village of Waakirchen, SS guards gathered the prisoners in a wooded area and began firing on them. Some were gunned down where they stood; others escaped death by hiding in the snow.

Solly Ganor described that terrifying night:

“The SS began shooting us. I wasn’t hit. I collapsed and fell asleep, thinking I was dead. I awoke covered in snow, which had insulated me from the cold. In the distance, I heard trucks. At first, I feared they were the Japanese army—but they were American soldiers. One approached, knelt beside me, and offered me a Hershey’s chocolate bar. That moment saved my life. I realized I was free. These men, with their unfamiliar faces, were like angels sent from Heaven.”

The liberators were part of the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion—Japanese American soldiers of the Nisei, many of whose families were at that moment incarcerated in U.S. internment camps. The SS and their collaborators, hearing the approach of American forces, had abandoned their mass execution and fled.

At first, the soldiers saw what looked like “lumps in the snow.” On closer inspection, they realized they were human beings—starved, skeletal, and barely alive.

George Goto, a member of the 522nd, later said:

“You can’t imagine what it was like. Their faces were hollow, their eyes sunken. They were just beaten human beings—beyond food, beyond hope. They were living skeletons.”

Clarence Matsumura, a communications specialist with Headquarters, recalled:

“We found hundreds of them lying in the open. Some were dead, others too weak to move. I told them, ‘You’re free. The war is over.’ Even if they didn’t speak English, they understood. We gave them food—some died because their bodies couldn’t handle it. I cried. I still feel guilty.”

Matsumura fainted from exhaustion and was revived by survivors, who fed him in return.

For three days, the 522nd remained in Waakirchen. The soldiers worked day and night to move the survivors into shelter—barns, abandoned homes, even evicting German families to make space. They provided blankets, socks, hats, and carefully rationed food—soft items like soup and powdered eggs to avoid shocking their starved bodies.

PFC Minabe Hirasaki of Charlie Battery recalled:

“We found a chicken ranch, killed the chickens, and fed the survivors. They were so thin—I’ll never forget those faces.”

Katsugo Miho of B Battery said:

“I saw Jewish families in Italy and felt sorry for them, but I never imagined anything like this was happening. I was told not to feed the survivors—but I fed them anyway.”

Survivors of the Dachau death march credit the 522nd not just with liberation, but with saving their lives. For many, it was the first act of compassion they had seen in over four years.

On May 4, 1945, the 522nd left Waakirchen. Alongside the 101st Airborne Division, they continued on to participate in the capture of Hitler’s mountain retreat at Berchtesgaden.

After the war, the 522nd was assigned to occupation duty in the town of Donauwörth. There, these same Japanese American soldiers—once treated with suspicion and imprisoned by their own government—befriended the local German population as they helped rebuild a shattered country.

sources

https://time.graphics/ru/event/4237386

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_marches_during_the_Holocaust#Dachau_to_the_Austrian_border

https://www.dvidshub.net/news/233592/nisei-field-artillery-liberated-wwii-prisoners

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment