Below is an estimate of the number of people who died as a result of the war, the occupation, and the persecution during the years 1940–1945.

The total number of Dutch people who died lies between 225,000 and 280,000. At that time, the population of the Netherlands was 9 million.

- 2,200 soldiers of the Dutch army were killed during the May days of 1940.

- The bombing of Rotterdam on May 14, 1940, claimed the lives of nearly 900 residents of the city.

- 258 soldiers died in German prisoner-of-war camps.

- 102,000 of the total 107,000 deported Jewish citizens from the Netherlands were murdered in Auschwitz, Sobibor, and other camps.

- 240 Roma and Sinti were murdered in Auschwitz.

- Approximately 4,400 of the 11,000 non-Jewish prisoners in concentration and penal camps died, many of them resistance members.

- 2,000 civilians were executed; some were resistance fighters sentenced to death, others were randomly selected prisoners who were shot in reprisals during the final phase of the war.

- 375 of the roughly 7,500 non-Jewish prisoners in German prisons died. Most had been imprisoned for “economic offenses” (black market trading, theft); others were political prisoners.

- 30,000 Dutch forced laborers in Germany died due to exhaustion, bombings, and other causes.

- It is estimated that between 6,000 and 14,000 civilians died during Allied bombings of Dutch cities (e.g., targeting German positions or so-called mistaken bombings).

- 20,500 civilians died in bombings and fighting in the front-line areas from September 1944 to May 1945. Most civilian casualties occurred during the Allied liberation efforts, beginning with the Battle of Arnhem in September 1944.

- 1,500 soldiers of the Princess Irene Brigade and the Domestic Armed Forces died in 1944–1945.

- 22,000 civilians in cities in Western Netherlands died due to hunger, cold, and illness during the Hunger Winter of 1944–1945. (The total number of people who died due to shortages and other poor conditions during the occupation is much higher; for example, many sick and elderly people could have survived if there had been enough medication.)

- 1,490 merchant navy crew members never returned from sea.

- No Dutch homosexuals were deported or killed solely because of their sexuality, unlike in Germany. However, there were criminal convictions and prison sentences, similar to those before and after the occupation in the Netherlands.

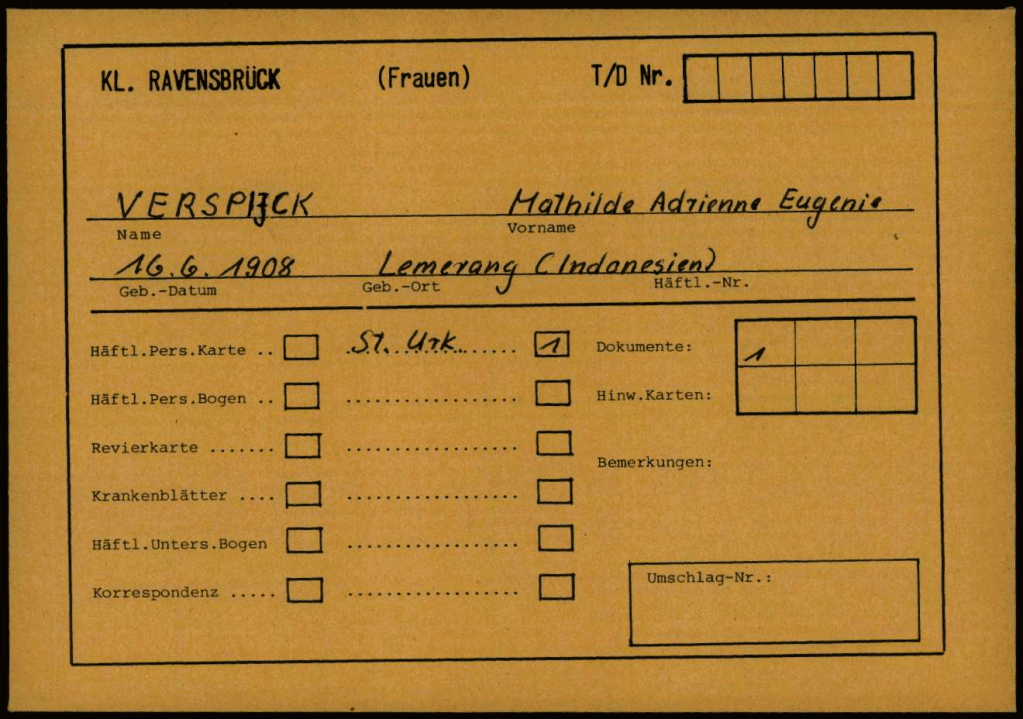

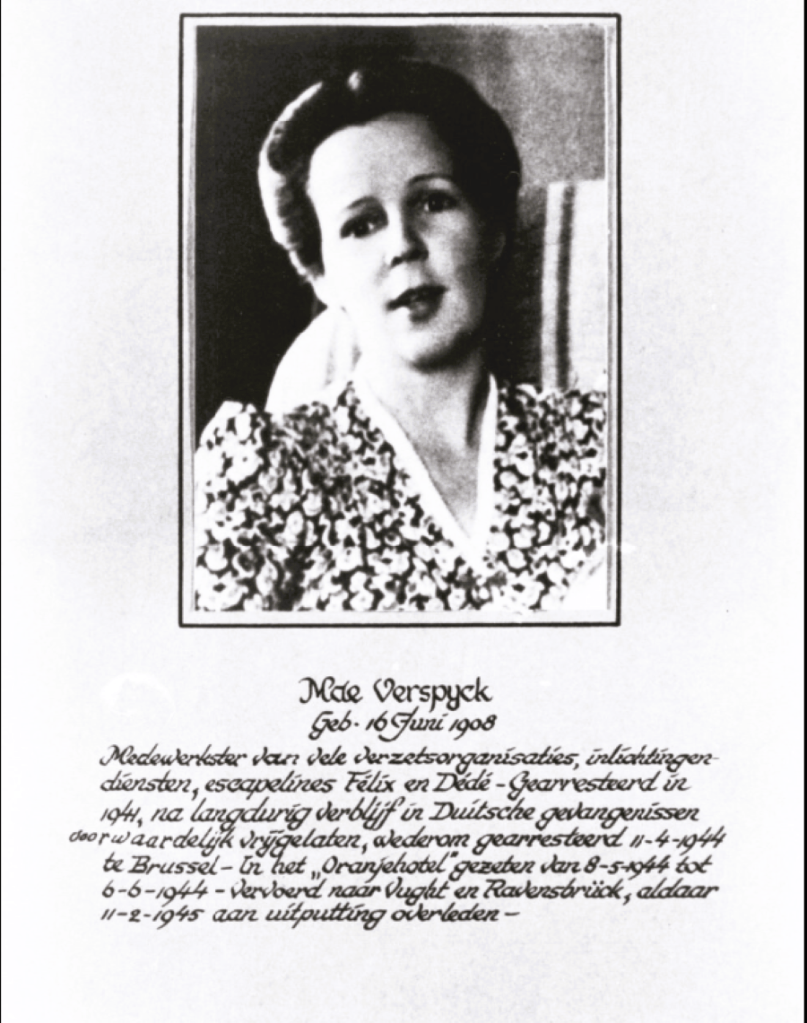

Mathilde Adrienne Eugènie Verspijck was just one of them.

Mathilde Adrienne Eugénie Verspyck (16 July 1908 – 11 February 1945) was described as “a brave woman who was a devoted believer in the cause of freedom, for which she later sacrificed her life,” according to her U.S. Medal of Freedom citation.

A dedicated resistance fighter, Verspyck played a vital role in European resistance movements during World War II. She survived imprisonment in one Nazi concentration camp, only to perish in another.

Between 1941 and 1943, she was arrested and imprisoned twice for her resistance work. Her third and final arrest came in April 1944 for sheltering political prisoners and Allied pilots, assisting their escapes, and engaging in espionage. Initially jailed in Scheveningen, she was transferred two months later to the Herzogenbusch (Vught) concentration camp in the Netherlands. Three months after that, she was deported to Ravensbrück in Germany, where she died on 11 February 1945.

Early Life

Mathilde Verspyck was born on 16 June 1908 in Semarang, Java. She was the granddaughter of Dutch general Rudolph Paul Verspyck and the daughter of Rudolph Hubert Marie Verspyck, a native of Bergen op Zoom, and his second wife, Mathilde Adrienne Prins. Her father was a partner in Dunlop & Kolff, a major brokerage firm operating in Batavia, Semarang, and Surabaya, trading in goods such as fish, sugar, and tea. Following her parents’ divorce around 1920, her father remarried in London in 1921.

Resistance Work During World War II

Following the German invasion and the Dutch surrender on 14 May 1940, Verspyck joined the resistance, working to rescue political prisoners and Allied airmen. She collaborated with the Comet escape line of the Belgian Resistance, providing food, clothing, forged documents, and safe houses to downed pilots. She also helped guide them through occupied France to neutral Spain, allowing them to return to Britain and resume their military service.

According to Dr. Bob de Graeff, a professor at Utrecht University, she was particularly active in Brussels. After her first arrest in November 1941 and subsequent release, she resumed her resistance activities. She was arrested again on 15 November 1943 and later released. On 12 April 1944 (some records cite 15 April), she was imprisoned for the third time. From Scheveningen, she was transferred to Vught and then to Ravensbrück, where she died in early 1945. Her father, who had also been captured, survived the war.

Historian Megan Koreman confirmed that Verspyck worked with Jan Strengers, a banker, and Paul Van Cleeff, a resistance member who passed Allied airmen to the Comet line through her.

Family Ties to the Resistance

According to Professor de Graeff, Verspyck’s father was also imprisoned for his involvement in resistance activities and survived the war.

Further evidence suggests that her mother, Mathilde Adrienne Prins, may also have participated in the resistance, or that their identities were sometimes confused in historical records. One account details how Olympic medalist and soldier Johan Jacob Greter was handed off to the Comet network by a resistance contact, who directed him to Mathilde “Mae” Verspyck at her home in Woluwé-Saint-Pierre. When she was arrested in October 1943, another resistance member helped Greter continue his escape via the Comet line. Greter later returned to England by submarine after recovering from severe hypothermia during his journey through the Pyrenees.

Final Days and Death

Mathilde Verspyck was arrested on November 8, 1941, and imprisoned in St. Gillis prison in Brussels. From there, she was transferred to Aachen on January 28, 1942, where she was released again on September 30, 1942. Upon returning home, however, she resumed her resistance activities. On November 15, 1943, she was arrested for the second time and again taken to St. Gillis prison. The following day, she was transferred to the prison in Antwerp, where she was held until November 23, 1943. She was released again, but when she was arrested for the third time and brought back to St. Gillis (on April 12, 1944), her luck had run out. On May 2, 1944, she was transferred to the Oranjehotel in Scheveningen, and from there, on June 6, 1944, to Camp Vught. On September 8, 1944, she was transported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp in Germany, where she died on February 11, 1945, as a result of the harsh treatment. On February 16, 1946.After surviving two months in Vught, Verspyck was deported to Ravensbrück. Initially resilient, she eventually succumbed to the brutal conditions, dying on 11 February 1945. Although one source, British intelligence officer Airey Neave, mistakenly listed her date of death as 11 May 1945, multiple authoritative sources confirm it was in fact 11 February.

Honors and Recognition

In recognition of her extraordinary efforts as a freedom fighter during World War II, Mathilde Verspyck was posthumously awarded two of the highest civilian honors:

The Dutch Verzetskruis (Cross of Resistance) in 1946

The United States Medal of Freedom

The U.S. Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian award, was granted for her courageous service in the resistance and the suffering she endured as a result. According to General Orders issued by the U.S. Department of Defense on 1 November 1946 and 20 March 1947:

“Mademoiselle Verspyck joined an escape organization soon after the capitulation and is considered by the head of the group to have rendered considerable and remarkable service to his evasion line. Not only did she shelter numbers of evaders, but she also carried on considerable convoy activities. She was always a willing and tireless helper, who could be called upon to carry out a difficult and dangerous task at short notice.

Mademoiselle Verspyck was arrested on 15 April 1944 because of her evasion activities and transported to Vught (Holland) in June 1944. She was deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp on 6 September 1944, where she died on 11 February 1945 owing to the hardship and ill treatment to which she had been subjected.

Mademoiselle Verspyck was a brave woman who was a devoted believer in the cause of freedom, for which she later sacrificed her life.”

The Verzetskruis, the second-highest Dutch decoration for valor, was awarded for her:

“Moed, initiatief, volharding, offervaardigheid en toewijding in den strijd tegen den overweldiger van de Nederlandsche onafhankelijkheid”

(“Courage, initiative, perseverance, sacrifice, and dedication in the struggle against the oppressor of Dutch independence”)

She was further honored for helping to preserve the “geestelijke vrijheid”—the spiritual freedom—of those she rescued.

sources

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mathilde_Verspyck

https://oorlogsgravenstichting.nl/personen/159935/mathilde-adrienne-eug%C3%A8nie-verspijck

https://www.tracesofwar.nl/persons/587/Verspijck-Mathilde-Adrienne-Eug%C3%A9nie.htm

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment