I once painted skies.

Vast, open, careless heavens that dripped sunlight and hope.

My brush danced with joy, my palette a chorus of life.

But then came the grey.

It was not the grey of morning mist or soft winter clouds—

It was the grey of silence,

of smoke that climbed like prayer

from chimneys built to erase names.

I was still an artist then,

though my canvas became the inside of my mind,

stained with faces—

thin as twigs,

eyes vast as questions no one dared to answer.

They took my tools.

They took my family.

But I remembered color.

In a place where numbers replaced names,

where death was routine,

I sketched with stolen charcoal

on scraps of stolen paper,

the curve of a cheek,

the whisper of a tree remembered.

Art became resistance.

A breath against the suffocation.

A scream with no sound.

We were not supposed to feel.

We were not supposed to dream.

But I drew the moon once—

silver, defiant—

above barbed wire,

and passed it hand to hand

like contraband hope.

I saw a child with eyes still full of stars.

I drew them so I wouldn’t forget

what the world looked like

before it went mad.

When liberation came,

I did not cheer.

I opened my eyes to a world

that had watched—

and still asked us to explain ourselves.

I paint again.

But every canvas begins with grey.

Beneath every flower,

there is ash.

Beneath every bright sky,

a shadow that remembers.

Because an artist must not only show what is—

but what must never be again.

This poem reflects what an artist might have expressed during the Holocaust. The accompanying images are drawings created by artists who lived through the Holocaust—some of whom survived, while others did not.

Charlotte Salomon was born into an assimilated Jewish family deeply engaged in Berlin’s cultural life. Despite the rise of antisemitic laws, she was admitted in 1935 to the Vereinigten Staatsschulen für Freie und Angewandte Kunst (United State Schools for Fine and Applied Arts) in Berlin.

Following the Kristallnacht pogrom on November 9, 1938, during which her father, Albert, was arrested, her parents made the difficult decision to send Charlotte to her grandparents, who had taken refuge in the south of France. There, under the shadow of Nazi persecution, Charlotte began work on her extraordinary autobiographical illustrated musical play, Life? or Theater?, a powerful visual narrative composed of more than 700 paintings.

In June 1943, she married Alexander Nagler, a fellow Jewish refugee. Just a few months later, in September, the couple was arrested and sent to the Drancy transit camp. On October 7, they were deported to Auschwitz. Charlotte, pregnant at the time, was murdered upon arrival. Alexander died of exhaustion on January 1, 1944.

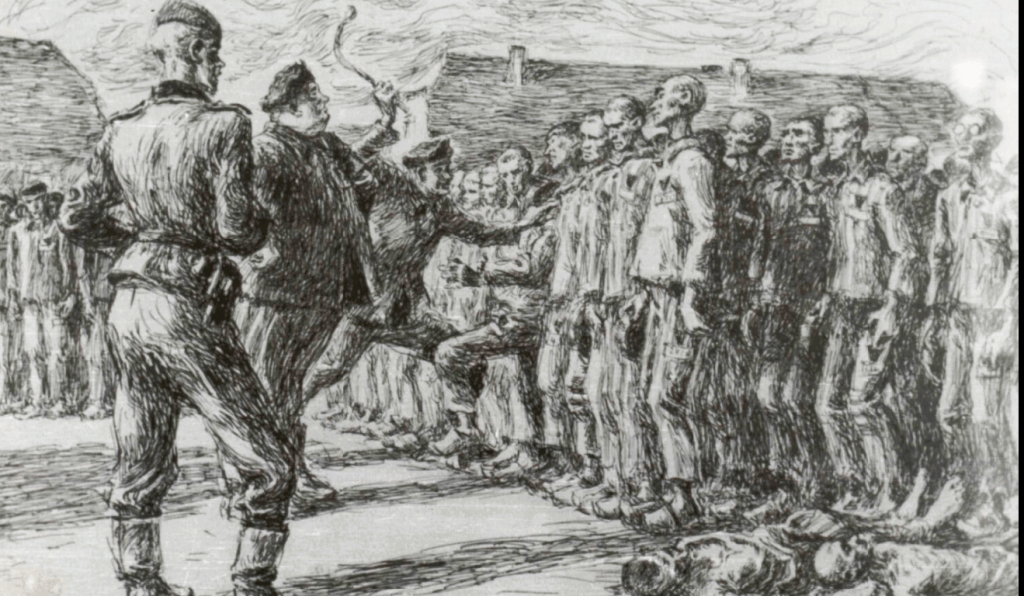

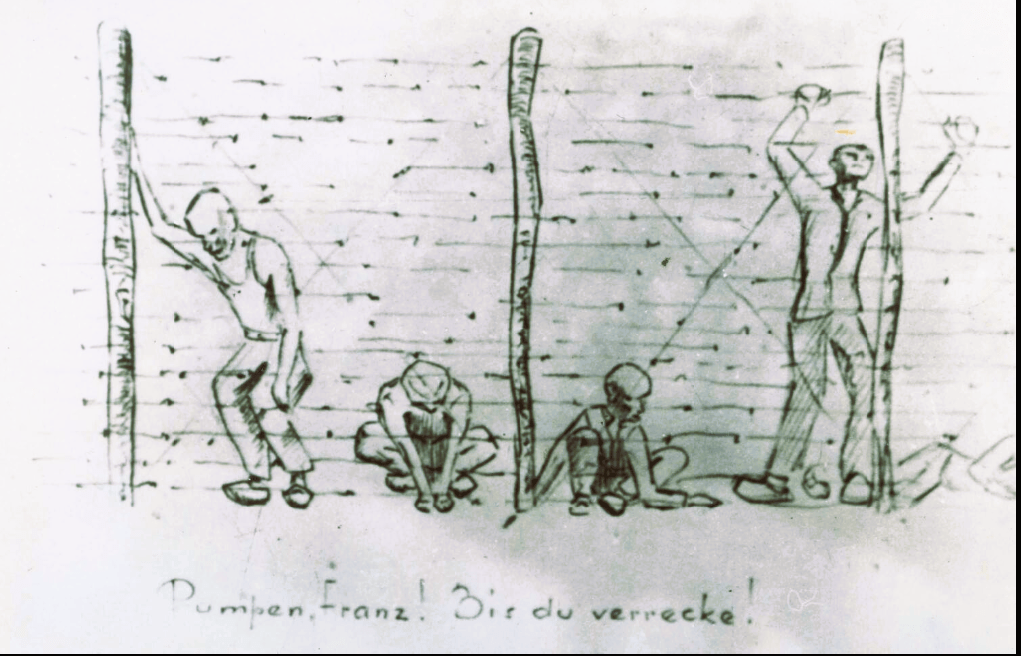

After graduating from the Vilnius Academy of Arts, Jacob Lipschitz remained at the institution to teach printmaking. Alongside his academic work, he illustrated textbooks and participated in numerous exhibitions.

In June 1941, following the German invasion, Lipschitz was interned in the Kovno ghetto with his wife, Lisa, and their daughter, Pepa. Assigned to a forced labor brigade, he worked in the ghetto workshops by day and painted in secret at night in an attic. Later, he joined fellow artist Esther Lurie and a circle of others who sought to document life in the ghetto through their art.

Fearing the increasingly brutal Aktions (round-ups and mass executions), Jacob and Lisa arranged for their daughter Pepa to be smuggled out of the ghetto. She was sheltered by the Zabielavičius family, Christian rescuers who risked their lives to protect her.

When the Kovno ghetto was liquidated in the summer of 1944, Lipschitz was deported to the Dachau concentration camp, and later to the Kaufering forced labor camp. Weakened by the inhumane conditions and deteriorating health, he died there in March 1945.

After the war, Lisa and Pepa returned to the ruins of the ghetto and recovered Jacob’s hidden paintings, which had been buried in the cemetery—fragile, defiant remnants of a life and legacy nearly lost.

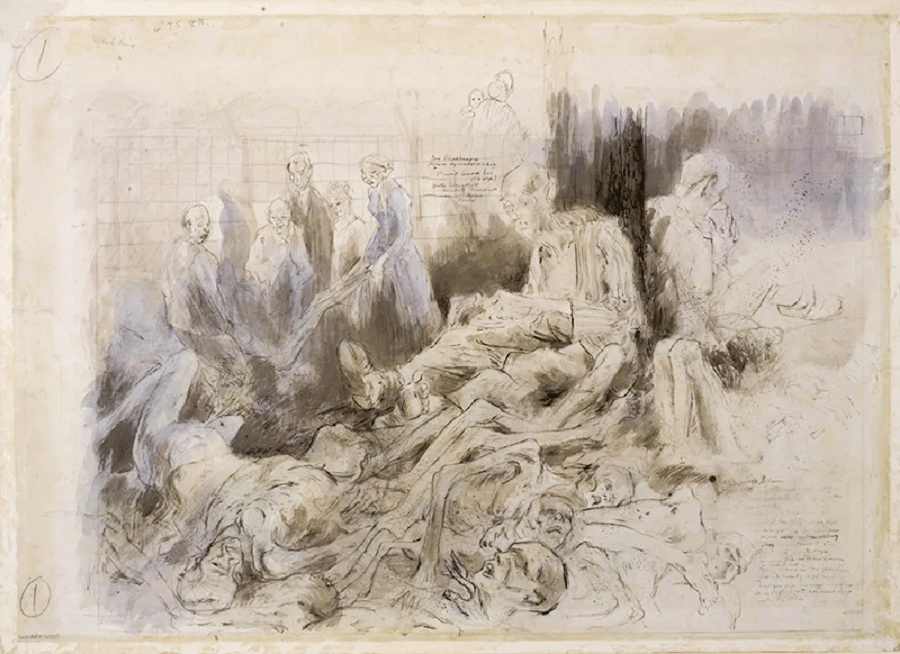

“I went to Belsen shortly after it was liberated. I saw the horrors of mass death. I was nauseated, as every other sane human would be. But it wasn’t the piles of rotting dead that fascinated and horrified me—it was the condition of the still living.”

As Art Editor for Picture Post magazine, Edgar Ainsworth (1905–1975) visited Bergen-Belsen three times in the months following its liberation. Through his drawings, he documented the harrowing transformations he observed in the survivors over time.

Alongside other official war artists such as Leslie Cole and Doris Zinkeisen, Ainsworth sought to record the unimaginable atrocities uncovered at the camp—not just for history, but to convey the scale and impact of what had occurred. Their work served as both testimony and warning.

In Belsen 1945, one of Ainsworth’s most haunting pieces, a survivor lies almost indistinguishable among the pile of corpses. The blue wash he used evokes the pallor of death, blurring the line between the living and the dead—a stark visual metaphor for the profound trauma endured by those who survived.

Sources

https://wwv.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/art/index.asp

https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/artists-responses-to-the-holocaust

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment