Hedy Lamarr, born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in 1914 in Vienna, Austria, is best known for her work as a Hollywood actress during the Golden Age of cinema. However, her contributions to science and technology, particularly her co-invention of a technology that laid the groundwork for WiFi, Bluetooth, and GPS, have garnered increasing recognition. Lamarr’s dual identity as both an actress and an inventor speaks to her remarkable intellect and creativity, as well as her pioneering spirit in a time when women’s contributions to science were often marginalized or ignored.

Early Life and Hollywood Fame

Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in 1914 in Vienna, the only child of Gertrud “Trude” Kiesler (née Lichtwitz) and Emil Kiesler.

Her father was born to a Galician-Jewish family in Lemberg in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, part of the Austrian Empire (now Lviv in Ukraine), and was, in the 1920s, deputy director of Wiener Bankverein, and at the end of his life a director at the united Creditanstalt-Bankverein. Her mother, a pianist and a native of Budapest, had come from an upper-class Hungarian-Jewish family. She had converted to Catholicism and was described as a “practicing Christian” who raised her daughter as a Christian, although Hedy was not baptized at the time.

Hedy Lamarr began her career in Europe, becoming famous in the 1933 Czech film Ecstasy, which caused controversy for its scenes of nudity and realistic depiction of female sexuality and orgasm. The film’s international scandal, combined with Lamarr’s undeniable beauty, brought her to the attention of Hollywood. She moved to the United States and signed with MGM, quickly becoming one of the most glamorous actresses of her time. Starring in films such as Algiers (1938), Boom Town (1940), and Samson and Delilah (1949), Lamarr captivated audiences with her beauty and charisma, earning the nickname “The Most Beautiful Woman in the World.”

Yet, despite her fame in Hollywood, Lamarr grew bored with the roles available to her and often felt intellectually unfulfilled. In interviews, she would later express frustration at being typecast based on her appearance, lamenting that people often only recognized her beauty, overlooking her intelligence and scientific interests.

Scientific Curiosity and the Beginnings of an Invention

Hedy Lamarr’s interest in science and invention was rooted in her curiosity and intelligence, which her acting career could not fully satisfy. She began inventing on her own, working on projects during her downtime on movie sets. Lamarr was self-taught; she had no formal scientific education, yet her natural aptitude and inquisitive nature drove her to pursue her ideas in the face of societal expectations.

Her most significant invention emerged during World War II. Disturbed by news of German submarines attacking Allied ships, Lamarr was inspired to find a way to help the U.S. Navy counter these attacks. She understood that radio-controlled torpedoes, which were an emerging technology at the time, were vulnerable to interference or jamming by the enemy. To address this, Lamarr devised a frequency-hopping system that could guide torpedoes without the risk of interception.

Collaboration with George Antheil: The Birth of Frequency Hopping

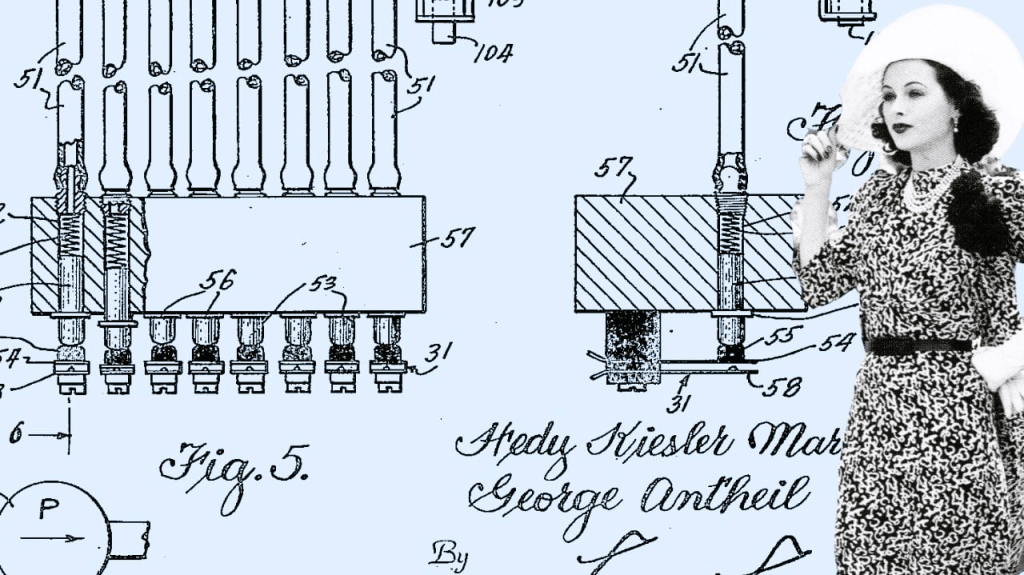

Lamarr collaborated with composer and inventor George Antheil to bring her idea to life. Antheil was well known for his experimental compositions, and his work on synchronized player pianos inspired Lamarr. Together, they developed a system in which the frequency of the radio signal would rapidly change according to a pre-set pattern, making it nearly impossible for enemy forces to jam the signal, as they would not know the specific frequency sequence.

On August 11, 1942, Lamarr and Antheil received a patent for their invention, officially known as a “Secret Communication System.” The patent outlined the use of 88 different frequencies (a number inspired by Antheil’s piano keys) to prevent interference. Despite the ingenuity of the design, the U.S. Navy was not interested in implementing the technology during the war, as they believed it would be difficult to incorporate into their existing systems. The invention was shelved and largely forgotten for decades, with neither Lamarr nor Antheil receiving any royalties or recognition.

The Impact on Modern Technology: From Frequency Hopping to WiFi

Although the Navy initially disregarded Lamarr’s invention, the principles of frequency hopping were revisited in the 1950s and 1960s during the development of secure military communications. By the 1980s, frequency hopping became a fundamental technology in wireless communication, as it allowed devices to avoid interference and communicate securely over shared frequencies. This technique became particularly valuable as the groundwork for WiFi, Bluetooth, and GPS technology.

WiFi, in particular, uses spread-spectrum and frequency-hopping techniques that are direct descendants of the concepts outlined in Lamarr and Antheil’s original patent. As WiFi networks allow devices to connect without the risk of interference from other devices, Lamarr’s invention can be seen as the precursor to the seamless wireless communication technologies that have become an essential part of daily life. Her work set the stage for innovations that power everything from smartphones to home internet networks to satellites.

Recognition and Legacy

In her later years, Lamarr began to receive acknowledgment for her contributions to technology. In 1997, the Electronic Frontier Foundation awarded her and George Antheil a special award, honoring them for their invention. Today, Lamarr is often celebrated as an early female pioneer in STEM, a field that remains male-dominated but is increasingly recognizing the contributions of women. The legacy of her invention lives on in the technology that keeps people connected worldwide, underscoring her role as a visionary well ahead of her time.

Lamarr’s story highlights the barriers that women, especially those in the public eye, have historically faced in being recognized for their intellectual contributions. Despite being overshadowed by her Hollywood persona during her life, Lamarr’s technological contributions continue to impact the world. The story of Hedy Lamarr serves as an inspiring reminder of the importance of diverse perspectives in science and technology, as well as the resilience required to push the boundaries of knowledge and understanding. Today, as we rely on WiFi and related technologies, Lamarr’s contributions remind us that talent and innovation often come from unexpected places.

Sources

https://standards.ieee.org/beyond-standards/hedy-lamarr/

https://www.invent.org/inductees/hedy-lamarr

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment