It should come as little surprise that away from the carnage of the Western Front, soldiers sought solace in whatever pleasures they could find. Amid the chaos of the First World War, the harsh realities of trench warfare often fueled desires as primal as the will to survive.

During the bloodiest phases of the war, the average lifespan of a British junior officer was a mere six weeks. Over one in ten British soldiers who enlisted—or were conscripted—never returned home. Faced with the constant specter of death, soldiers developed an insatiable appetite for life’s fleeting joys, including those offered in French brothels or maisons tolérées. By 1917, at least 137 such establishments operated across 35 towns in Northern France, catering to a steady stream of British servicemen cycling through the front lines, reserve trenches, and nearby towns.

In many of these towns, the war seemed almost distant. The thunder of artillery in the background was often the only reminder of the carnage a few miles away. With most Frenchmen of fighting age deployed elsewhere, the arrival of British soldiers filled the void—both militarily and socially. Stories abound of British Tommies forging bonds, fleeting and otherwise, with the local population. One veteran even boasted of seducing a French girl within minutes of stepping off his train, consummating the encounter on the station’s grassy verge.

According to his tale, the same soldier later lodged with an elderly Frenchman and his beautiful granddaughter, who supposedly brought him coffee in bed each morning—before climbing in beside him, blissfully unaware of her grandfather’s presence. Such tales, true or embellished, reflect the desperate vitality that wartime life inspired.

For less romantically inclined soldiers—or those lacking charm—the brothels offered a more straightforward alternative. These venues thrived, with some servicing astonishing numbers: a single brothel-lined street reported 171,000 customers in just one year. The infamous Red Lamp brothel in Béthune, marked by its glowing sign, became a landmark for British troops. Lines of soldiers waiting outside were likened by newcomers to the queues for football matches back home.

Inside, the conditions were as cramped as the trenches, albeit far livelier. Soldiers would pay a franc to enter a café-like area, where alcohol flowed freely, before ascending to the rooms upstairs for an additional five francs. Yet even at these prices—equivalent to a week’s wages—there were no guarantees of prompt satisfaction; men often waited on staircases for their turn.

For many, these encounters were formative. Private William Roworth, who had lied about his age to enlist at just 15, recorded his first sexual experience during his time in Northern France. His youthful innocence shines through in his diary entry: “It was like pulling your thing, but you have someone to talk to.”

Not everyone was as unfulfilled as Roworth. Lieutenant R. Graham Dixon, for instance, described the maisons tolérées as a vital outlet for soldiers’ physical energy. He was particularly fond of a “black-eyed, black-haired wench” at a brothel in Dunkirk, praising her “adequate enthusiasm and skill.” Dixon’s haunt was likely one of the exclusive “blue lamp” brothels reserved for officers. These establishments catered to their elite clientele with added perks, including pills to enhance performance—an early precursor to Viagra.

Many young soldiers sought out these prostitutes, desperate to lose their virginity.

Others hoped to pick up a sexually transmitted infection (STI), with the ensuing month spent in the hospital delaying the horrors of the front line.

It wasn’t just young, unmarried men who sought refuge in these brothels. Contemporary accounts describe older, married soldiers queuing up, driven by longing for their wives. Surprisingly, the British Army turned a blind eye to such activities, provided soldiers stuck to licensed brothels, and avoided contracting venereal diseases. Army chaplains were even available to absolve guilty consciences.

The risk of syphilis and gonorrhea was significant enough to capture the attention of military leadership. Lord Kitchener personally issued warnings to soldiers in their first pay packets, advising them to resist the temptations of “wine and women.” However, many soldiers, like Private Richards, dismissed this advice entirely, stating, “It may as well not have been issued for all the notice we took.”

For some individuals, the idea of contracting a disease became a twisted form of escape. Faced with the horrors of the trenches, spending a month in the hospital—even with basic treatments—seemed more desirable than going “over the top” into no-man’s-land.

The frequency with which British soldiers visited the maisons tolérées is perhaps best understood in the context of their dire circumstances. Staring death in the face daily inspired a “live for today” mentality that rendered future consequences irrelevant. Many of these young men arrived in France as virgins; others, married or not, found themselves unable to resist the temptations of fleeting intimacy.

It’s easy to judge these actions from the safety of history, but their extraordinary circumstances make such judgments futile. Instead, these stories remind us of the profound human need for connection—even amid the world’s darkest moments. In a war defined by brutality and loss, perhaps this offers a new perspective on the timeless adage: all is fair in love and war.

One significant outcome of the First World War was increased mobility. Millions of men were sent to the front, leaving behind their wives and families. This separation had profound effects on relationships and sexual behavior.

While estimates of the number of conscripted married men vary, it is likely that by 1918, around 6.5 million men from Austria-Hungary and 11 million from the German Empire were mobilized. Over a third of these men were married, meaning a substantial number of families were divided.

This separation created a gender imbalance at home, leading to a noticeable decline in marriages and births. Sexual relations between married couples were often interrupted for months or even years. A woman from the Allgäu region reflected on this in her memoirs, noting how the situation became normalized as the war progressed:

“We got used to the deprivation. We accepted that the men were away and that the women had to toil and look after the children. We could only write and send packages to our husbands.”

Despite the distance, sexual activity remained prevalent during the war, often occurring outside marriage. Soldiers engaged in relationships with women in occupied territories visited prostitutes in brothels near the front lines, and women at home formed relationships with foreign workers and prisoners of war.

These circumstances led to increased sexual mobility, new forms of relationships, and shifting moral norms.

This societal shift drew the attention of the state, which began to monitor and regulate sexual behavior more closely, both among troops and the civilian population. Public discussions of sexuality had already gained traction at the turn of the century, but the war accelerated this trend, politicizing the topic further.

Venereal diseases, which posed a serious threat to the combat readiness of soldiers, became a pressing concern. Governments prioritized prevention through measures such as regulating prostitution, promoting abstinence, and encouraging the use of contraceptives and other prophylactic methods. Another critical issue across all belligerent nations was the declining birth rate, which was seen as a threat to national strength and received significant attention.

Sexual Violence in Allied War Propaganda

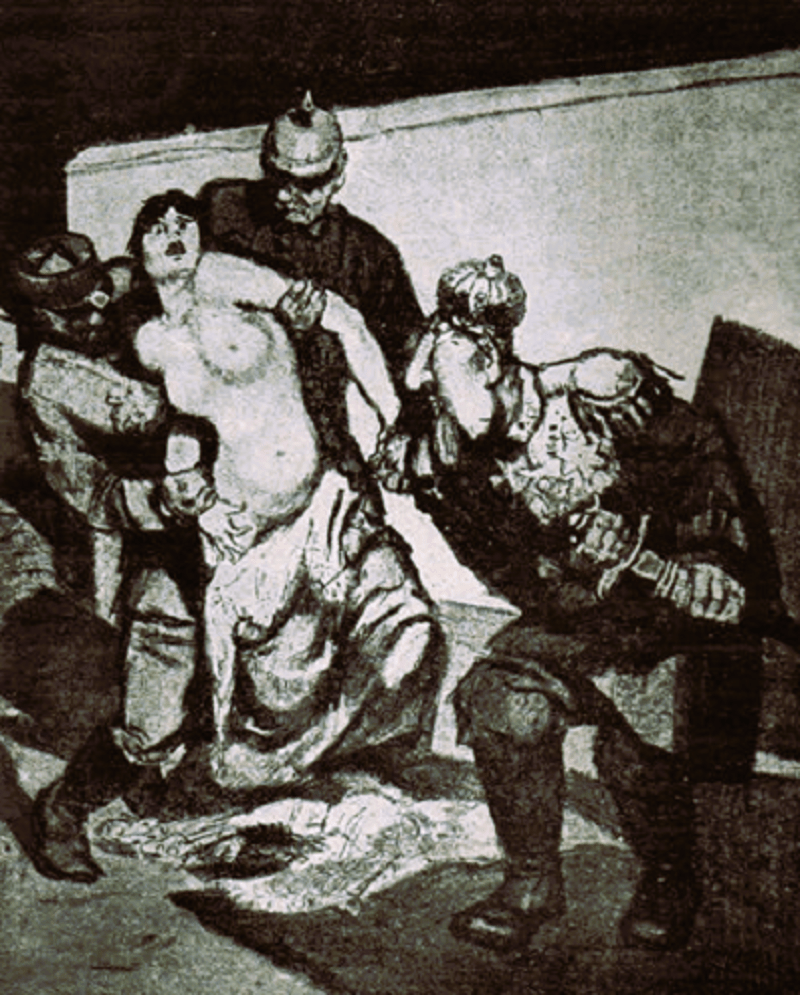

The harrowing acts of violence inflicted upon Belgian and French civilians by German troops became a cornerstone of Allied war propaganda, designed to stir outrage and galvanize support for the war effort. Gruesome images of defiled and mutilated women and children were circulated, portraying the enemy as monstrous and justifying the sacrifices demanded of Allied populations.

Between August and October 1914, German troops unleashed a wave of brutality upon Belgian and French civilians, leaving a trail of devastation that shocked the world. These “German atrocities” (“atrocités allemandes”) claimed the lives of 5,521 Belgians and 906 French civilians. Whispers of mass rape and grotesque mutilation spread like wildfire in the early weeks of the conflict. In response, Belgium, France, and Great Britain established a joint commission to investigate these crimes under the framework of the Hague Convention of 1907. The committee corroborated widespread reports of sexual violence, confirming that German soldiers had committed systematic assaults against the female civilian population.

While the exact number of women raped and mutilated remains shrouded in historical uncertainty, the scale of these atrocities left an indelible mark. For the Allies, these heinous acts became emblematic of German cruelty, fueling the narrative of an enemy devoid of humanity or morality. Tales of women being savaged, breasts mutilated, and children’s hands severed were widely circulated, painting Germany as a barbaric force with which peace was unthinkable. Whether entirely accurate or exaggerated, these nightmarish accounts proved pivotal in shaping public perception and rallying support for the war.

The specter of these atrocities served as a potent tool in the Allied propaganda machine, used to justify the ongoing conflict and the loss of countless lives. By framing the war as a moral crusade to protect women and children, Allied leaders infused the fight with an emotional urgency. The defense of family and sexual virtue became a rallying cry, motivating not only the British and French public but also aiming to sway neutral powers like Italy and the United States into action.

Central to this propaganda was the symbolic link between the female victims and their nations. The ravaged woman became a metaphor for a violated Belgium—a small, neutral country brutally assaulted by an aggressor. Allied posters frequently depicted innocent women terrorized by German soldiers, reinforcing the image of Germany as an uncivilized, malevolent force. This imagery evoked visceral emotions, portraying the war as not just a battle for territory but a defense of innocence and dignity against monstrous aggression.

The mass media at the time—tabloid newspapers, popular literature, postcards, and cartoons—amplified these depictions, cementing the image of “German barbarians” in the public consciousness. These narratives extended beyond the individual soldiers to encompass the entire German nation, which was cast as the embodiment of evil, capable of unspeakable acts. By emphasizing these atrocities, Allied propaganda solidified Germany’s role as the ultimate villain and provided moral validation for the continued war effort.

Through the lens of these atrocities, the Allies built a compelling justification for their cause. The harrowing tales of violence and the exploitation of female suffering became both a rallying cry for Allied citizens and a powerful tool to court international allies, ensuring that the horrors of war were etched into collective memory as both a warning and a call to arms.

Sources

https://ww1.habsburger.net/en/chapters/sexual-violence-allied-war-propaganda

https://ww1.habsburger.net/en/chapters/sexual-violence-allied-war-propaganda

https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/sexuality-sexual-relations-homosexuality

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment