Before delving into the main story, it’s important to discuss the events that led up to it.

The Farhud Pogrom: A Forgotten Tragedy

The Farhud, meaning “violent dispossession” in Arabic, was a devastating pogrom against the Jewish community in Baghdad, Iraq, on June 1–2, 1941. This dark chapter in Jewish history not only marked a turning point for Iraq’s ancient Jewish community but also reflected the broader geopolitical upheavals of the time.

The roots of the Farhud lay in the growing influence of fascist ideology in Iraq during the 1930s and 1940s. Nazi Germany’s propaganda, disseminated through Arabic-language broadcasts and local sympathizers, sought to fuel anti-Semitic sentiment in the Middle East. Iraq’s political instability further exacerbated these tensions. In April 1941, a pro-Axis coup led by Rashid Ali al-Gaylani briefly ousted the pro-British government, emboldening anti-Jewish elements. Although the coup was crushed by British forces by late May, the retreating authorities left a volatile power vacuum in Baghdad.

The pogrom began on the Jewish holiday of Shavuot. Rioters, including Iraqi soldiers, police, and civilians, rampaged through Jewish neighborhoods, looting homes, destroying synagogues, and murdering Jewish residents. Women were raped, and thousands were left homeless. Estimates of the death toll range from 180 to over 600, with many more injured. The Farhud’s ferocity shocked the Jewish community, which had coexisted with its Muslim and Christian neighbors for centuries.

The Farhud marked a watershed moment in the history of Iraqi Jews. Although the Jewish community in Iraq traced its lineage back over 2,500 years to the Babylonian Exile, the pogrom shattered their sense of security. Over the next decade, as anti-Semitic policies and hostility grew, most of Iraq’s Jews were forced to flee. Many of them fled to the Dutch East Indies, now known as Indonesia.

Between 1816 and 1949, the Dutch East Indies, was a Dutch colony. Between 1941 and 1945 it was occupied by Japan.

Before World War II, Indonesia was home to a diverse Jewish population that included Dutch Jews, Baghdadi Jews (primarily from Iraq and other parts of the Middle East), and refugees fleeing Nazi persecution in Europe. The Baghdadi Jews, predominantly settled in Surabaya, were involved in trade and commerce and had established a small but vibrant community.

In the 19th century, Jewish families began leaving Baghdad, driven by waves of persecution or lured by the expanding trade routes of the British Empire. Their journeys carried them to India, Singapore, Malaysia, Burma, Hong Kong, and Shanghai. The Indonesian archipelago, however, remained a relatively late destination. It was only when the Dutch East Indies took shape that a small but vibrant Jewish community emerged. Among them were a few thousand Ashkenazi Jews from Holland, joined by approximately 600 Baghdadi Jews who settled in Surabaya, the bustling port capital of East Java. For a time, their lives were marked by prosperity and stability—until the dark clouds of World War II gathered over the Pacific.

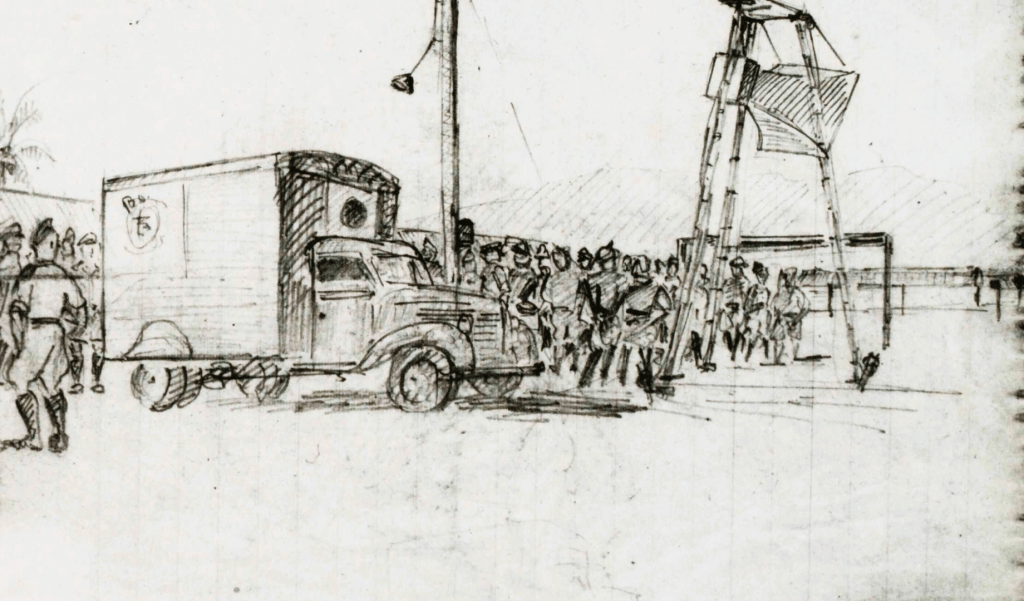

The war brought upheaval. Surabaya’s Jewish community swelled as refugees fleeing Nazi persecution in Europe sought sanctuary. But the sanctuary was short-lived. When Japanese forces occupied Java in early 1942, Dutch civilians, including Jews, were swiftly interned. By late 1943, under pressure from the Gestapo, the Japanese launched a campaign of anti-Semitic terror. Baghdadi Jews, targeted solely for their faith, were rounded up and sent to internment camps.

This harrowing and little-known chapter of history has been brought to light by the research of Rotem Kowner of Haifa University and, more recently, by Australian journalist Deborah Cassrels. Her interviews with survivors for an upcoming book have unveiled chilling stories of endurance and suffering. She recounted these tales during a poignant “Lockdown Lecture” hosted by Harif, the UK Association of Jews from the Middle East and North Africa.

Beginning in 1943, Jews were segregated by gender and imprisoned in four camps. In one, inmates were forced to construct a railway that was never completed. Hunger was an unrelenting adversary. Prisoners scavenged for anything edible—worms, snails, stray dogs. Disease was rampant. Infections from mosquito bites and ailments like amoebic dysentery claimed lives and weakened spirits.

The stories of individual survivors are searing. Edward Abraham, just five years old, lost his father after the man consumed raw cassava, a root that can be toxic if improperly prepared. Edward’s pregnant mother endured a cruel punishment—forced to stand all day staring into the sun, denied food and water, until she collapsed. Solomon Elias vividly recalled how his sister Hannah, caught trading jewelry for rations, was thrown into a rat-infested dungeon for two weeks. The Japanese guard who aided her was executed. The trauma followed Hannah for the rest of her life.

Sybil Sassoon, also pregnant, faced torment of her own. A Japanese officer pressed a pistol to her temple, demanding she deliver her child to the local hospital.

Thankfully, her baby arrived safely, but thirst and deprivation marked her days in the camp. During a train journey, prisoners desperately cupped their hands to catch rainwater. Despite their suffering, they clung to their faith—on Yom Kippur, they asked the guards to withhold their meager rations of worm-infested rice and vegetables, requesting tea and bread after sunset instead.

Benjamin David, just four years old at the time, recalled eating banana peels and gathering green beans off the ground. When his mother tried to boil water for soup, the guards cruelly poured the scalding water over her hands.

Even after Japan’s defeat in 1945, the nightmare was not over. The Jewish survivors found themselves caught in the violent throes of Indonesia’s anti-colonial struggle. The brutal fight for independence brought its own dangers, forcing many Jews to leave the archipelago for good.

Today, the last survivors of this ordeal are in their nineties, scattered across Australia, California, and Israel. The Jewish presence in Java has all but vanished; fewer than ten Jews remain in the region. Yet the memories of their resilience and suffering endure a testament to the strength of the human spirit even in the darkest of times.

Contrasting Treatment of Jews in Kobe, Japan, and Japanese-Occupied Indonesia

The Jewish population in Kobe, Japan, experienced a starkly different fate compared to their counterparts in Japanese-occupied Indonesia.

With the outbreak of World War II, Rahmo Sassoon and other Jews in Kobe found themselves unable to travel or conduct business. Despite these challenges, they were treated relatively well by the Japanese authorities. For instance, as German officers began appearing on the streets of Kobe during the war, anxiety grew among the Jewish community, particularly those who had helped smuggle European Jews to safety in Japan. In response to the growing fear, Rahmo Sassoon painted over the gold letters on the Ohel Shelomoh synagogue to make it less conspicuous.

Shortly thereafter, Sassoon was invited to meet with the Chief of Police of Kobe. During their meeting, the Chief inquired about the removal of the lettering. Sassoon explained that the community was anxious about the visible German presence in Kobe and Japan’s alliance with Nazi Germany. The Chief reassured Sassoon that the Jewish community had nothing to fear in Japan and instructed him to restore the lettering above the synagogue’s doorway.

During World War II, Kobe accepted a significant influx of Jewish refugees. Even though Japan was allied with Nazi Germany, the treatment of Jews in Kobe was notably different. From 1940 to 1941, the community in Kobe played a vital role in helping Holocaust refugees. Japan’s policy toward Jews contrasted sharply with that of their allies. While Japanese officials were generally unfamiliar with Jewish customs and practices, their actions stemmed from a perception that Jews were highly influential on a global scale.

This perception was shaped in part by Jacob Schiff, a Jewish financier who had raised substantial funds for Japan during the Russo-Japanese War in 1904. Schiff’s contributions left a lasting impression, demonstrating to Japanese leaders that Jews were skilled in business and possessed strong international connections.

Yasue Norihiro (also known as Yasue Senkoo) and Inuzuka Koreshige, key figures in the Manchurian faction within the Japanese government, sought to leverage Jewish influence to support their plans in Manchuria. Their strategy involved treating Russian, Sephardic, and German Jewish refugees under Japanese rule with respect, hoping this goodwill would prompt Jews in East Asia to advocate for financial and political support from their influential counterparts in the United States.

Additionally, the Japanese believed that their humane treatment of Jews might improve Japan’s strained relationship with the United States. They also saw German Jewish refugees as valuable contributors, particularly in terms of their scientific knowledge.

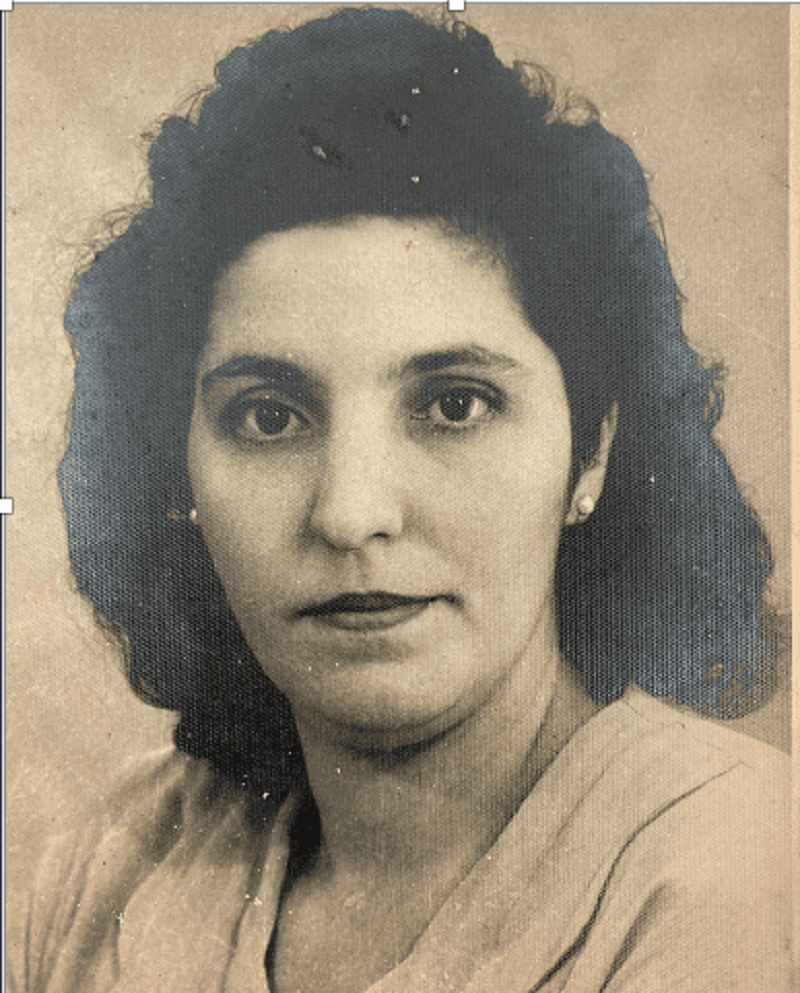

The Changing Atmosphere in Kobe as Pearl Harbor Approached

As the attack on Pearl Harbor loomed, the atmosphere in Kobe began to shift significantly. Japanese authorities grew increasingly wary of foreigners within Japan, and Kobe, with its visibly diverse foreign population, became a focal point of concern.

A decision was made to deport Jews who had not been residents of Kobe before the war to Shanghai. The port city of Kobe was being prepared for the impending conflict, necessitating the removal of many refugees.

For those who had enjoyed a relatively comfortable life in Kobe, the news of deportation was unwelcome. However, most recognized that their survival remained likely, and they were grateful to have escaped the horrors of the Holocaust in Europe.

Thanks to Norman Stone for drawing my attention to this story.

Sources

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-farhud

https://shc.stanford.edu/arcade/interventions/farhud-forgotten-ordeal-iraqi-jews

https://xenon.stanford.edu/~tamar/Kobe/Kobe.html

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a reply to tzipporahbatami Cancel reply