On the night of November 9–10, 1938, a wave of orchestrated violence swept across Germany and Austria. Jewish homes, businesses, and synagogues were burned and looted; families were beaten and humiliated; and tens of thousands were sent to concentration camps. The shattered glass that littered the streets the next morning gave the pogrom its haunting name: Kristallnacht, the “Night of Broken Glass.”

But Kristallnacht was not an isolated event. It was the culmination of years of growing anti-Jewish hatred, propaganda, and systematic dehumanization. It marked a decisive turning point in Nazi Germany’s treatment of Jews—from social exclusion to open violence and terror. To understand the magnitude of this night, we must trace the currents of ideology, politics, and fear that led to it.

The Rise of Nazi Ideology and the Seeds of Hatred

Anti-Semitism was not new to Europe in the 1930s. For centuries, Jews had been scapegoated for economic crises, blamed for wars, and portrayed as outsiders. But Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party turned this ancient prejudice into a political weapon.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, he brought with him a virulent racial ideology that placed Jews at the center of Germany’s supposed decline. In Mein Kampf, he had already declared Jews to be the arch-enemies of the Aryan race and the masterminds behind communism and capitalism alike. This ideological foundation justified, in Nazi eyes, the need to “purify” the German nation.

Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels used newspapers, films, and rallies to spread the message. Posters and speeches blamed Jews for unemployment, inflation, and moral decay. In classrooms, children were taught to see Jewish classmates as dangerous and subhuman. By systematically eroding empathy and normalizing hate, the Nazis created a society that could look away—or even cheer—when persecution escalated.

From Discrimination to Exclusion: The Road to 1938

The Nazi regime wasted little time translating words into policy. The boycott of Jewish businesses in April 1933 was one of the first organized acts of state-sponsored discrimination. SA (Sturmabteilung) members stood outside Jewish shops, painting the Star of David on windows and warning customers to stay away.

Then came the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which institutionalized racial discrimination. These laws stripped Jews of German citizenship, prohibited marriages and sexual relations between Jews and “Aryans,” and defined Jewishness by ancestry rather than religious affiliation. A person with three or four Jewish grandparents was classified as a Jew even if they no longer practiced Judaism.

Economic and social exclusion soon followed. Jews were forced out of government jobs, teaching positions, and professional associations. Their businesses were “Aryanized” — transferred to non-Jewish ownership under duress or at unfair prices. They were barred from public spaces, theaters, and universities.

By 1938, German Jews had become a marginalized, impoverished community living under constant fear. Many sought to emigrate, but few countries were willing to accept large numbers of refugees. International conferences, like the Evian Conference in July 1938, revealed the world’s reluctance to open its doors. This lack of global response emboldened the Nazi regime to escalate its persecution.

The Spark: The Assassination of Ernst vom Rath

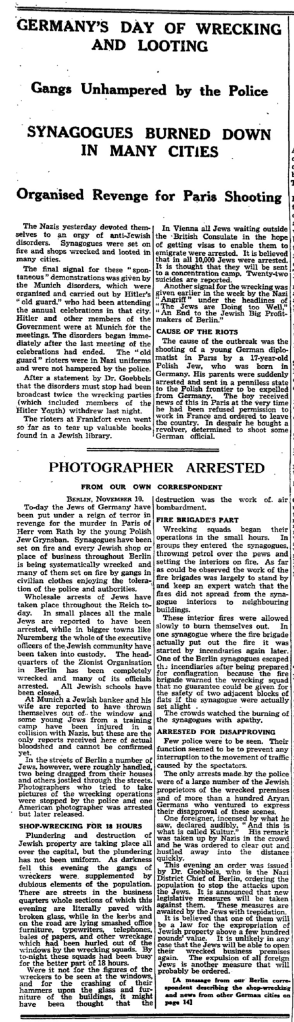

The immediate pretext for Kristallnacht came in early November 1938. A 17-year-old Polish-Jewish refugee named Herschel Grynszpan, living in Paris, learned that his parents and thousands of other Polish Jews had been expelled from Germany and stranded on the border in horrific conditions.

In despair and anger, he went to the German embassy in Paris and shot diplomat Ernst vom Rath, who died two days later.

The Nazi leadership seized upon the assassination as an opportunity. Joseph Goebbels, eager to prove his loyalty to Hitler after political missteps, framed the event as evidence of an international Jewish conspiracy against Germany. He incited party officials to “let the people’s anger run free” — a euphemism for coordinated violence.

On the night of November 9, as Nazi officials gathered in Munich to commemorate the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, orders were issued to local party units, SA, and SS members to attack Jewish targets. The police were instructed not to interfere unless non-Jewish property was threatened.

The Night of Broken Glass

What followed was one of the most devastating nights in modern European history. Across Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland, mobs vandalized Jewish neighborhoods with brutal precision. Synagogues burned as firefighters stood by, forbidden to intervene. Shop windows were smashed, their contents looted or destroyed. Homes were invaded, their occupants beaten and humiliated.

An estimated 7,500 Jewish businesses were destroyed, 267 synagogues burned, and 91 Jews murdered. In the days that followed, approximately 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps such as Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen. Many were tortured, starved, or killed.

The Nazi regime quickly turned the atrocity into a financial and political weapon. The Jewish community was forced to pay a “fine” of one billion Reichsmarks for the damage. Insurance payouts for destroyed property were confiscated by the state. The message was unmistakable: Jews had no place in Germany, and no protection under its laws.

Aftermath and International Reaction

The world was shocked, but largely passive. Foreign newspapers reported the violence, and a few governments recalled ambassadors in protest, but there was no coordinated international action. The United States temporarily withdrew its ambassador but did not alter its immigration quotas. Britain responded by creating the Kindertransport program, allowing some 10,000 Jewish children to seek refuge, but adults were largely left behind.

Inside Germany, Kristallnacht marked a point of no return. Many Jews now understood that the Nazi regime was not simply discriminatory but deadly. Emigration surged—but with few countries willing to receive them, options were limited. For the Nazi leadership, the pogrom served as both a test and a precedent: mass violence against Jews could be executed publicly and without meaningful consequence.

From Kristallnacht to the Holocaust

Kristallnacht was not the beginning of Nazi anti-Semitism, but it was the moment it became openly violent and state-sanctioned. It shattered the illusion that Jews might somehow endure under Nazi rule or that persecution would stop short of physical annihilation.

Within three years, the ghettos of Eastern Europe were overflowing, and mobile killing units (Einsatzgruppen) were executing mass shootings. By 1942, the “Final Solution” — the systematic extermination of European Jewry — was underway. Kristallnacht was, in retrospect, the prelude to genocide.

Remembering the Broken Glass

Today, Kristallnacht stands as a symbol of what happens when hate is normalized and silence prevails. The shards of glass that glittered on German streets in 1938 reflected not only the flames of burning synagogues but the fragility of civilization itself.

It reminds us that atrocities do not begin with concentration camps. They begin with words — with propaganda, scapegoating, and small acts of exclusion that go unchallenged.

To remember Kristallnacht is to remember our collective responsibility to confront hatred before it becomes violence. It is a call to vigilance — to ensure that the lessons written in broken glass are never forgotten.

Testimonies

1. Ruth Klüger – Vienna, Austria

“I remember my father standing helpless in the middle of our living room while men in uniforms tore our furniture apart. My mother kept whispering to me, ‘Don’t cry, Ruth, don’t cry.’

Then one of them smashed the glass cabinet where my grandmother’s dishes were kept. The sound of breaking glass — it went on and on. That’s what I remember most. The sound.”

2. Hans Jonas – Mönchengladbach, Germany

“They came in trucks and broke every window of the synagogue. I was sixteen. I watched from behind a fence as they threw the Torah scrolls into the street and set them on fire.

The rabbi was standing there in tears, and no one helped him. The fire brigade came — but only to make sure the flames didn’t spread to the houses next door.”

3. Hilde Sherman – Dinslaken, Germany

“Our neighbor — someone we’d known all our lives — pointed out our house to the Nazis. They smashed the windows and took my father away.

The next morning, we went to the synagogue. It was a heap of ashes. I was fourteen. That was the day I understood that we were completely alone.”

4. Victor Klemperer – Dresden, Germany (from his diary, November 1938)

“For hours the noise of smashing and breaking; the light of fires in the night sky. The police stood by, the firemen too, all passive.

When I ventured outside the next morning, the synagogue was in ruins, the shops destroyed. And everywhere the glint of broken glass — millions of tiny mirrors reflecting our humiliation.”

5. Edith Hahn Beer – Vienna, Austria

“They came into our apartment in the middle of the night. They tore down our curtains, smashed the dishes, and dragged my father away.

I was shaking so hard I couldn’t even scream. Outside, I could hear people laughing — our neighbors. That was the worst part: the laughter.”

6. Karl Adler – Stuttgart, Germany

“We had a piano, and they broke it with rifle butts. They ripped open the feather pillows so that feathers were flying everywhere like snow.

When they left, they told my mother, ‘You have one day to leave or you’ll be sent to a camp.’ My father was arrested the same night. We didn’t see him for months.”

7. Eva Schloss – Vienna, Austria (step-sister of Anne Frank)

“We were woken by the sound of shouting and glass breaking. My father looked out the window and said, ‘They are burning the synagogue.’

The next day, we saw it — a blackened shell, smoke still rising. My schoolteacher didn’t look me in the eye. She just said, ‘Don’t come back.’”

8. Hans Müller – Cologne, Germany (non-Jewish witness)

“The synagogue was burning, and the sky was red. The firefighters stood there, hoses ready, but they didn’t spray water on the building.

I asked one of them why, and he said: ‘We have our orders — Jewish property must burn.’ That sentence has never left me.”

9. Inge Deutschkron – Berlin, Germany

“The night after the synagogue burned, the air smelled of smoke and hatred. My father was taken to Sachsenhausen.

I was sixteen, and I remember thinking, ‘The world doesn’t care. We are nothing now.’ It was the end of everything we knew.”

10. Leo Baeck – Berlin, Germany (Chief Rabbi of Germany)

“Our houses of prayer were burning, but not one church bell rang in sympathy. The silence of the night was filled only with the crackle of flames.

That silence was perhaps more frightening than the fire itself.”

sources

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/kristallnacht

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/kristallnacht-night-broken-glass

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kristallnacht

https://wwv.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/kristallnacht/index.asp

https://www.jmberlin.de/en/topic-9-november-1938

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment