I always considered myself to be a bit of a World War II buff, but it was only when I started this website I realized how little I knew about World War II. This case is a good example.

Venlo is a town in the province of Limburg in the Netherlands, in the Southeast of the country. Bordering Germany in the East and Belgium in the West and South. The same province I was born and grew up in (albeit in the Southern part) and yet I had never heard of the “Venlo Incident,” an event that happened tomorrow 77 years ago.

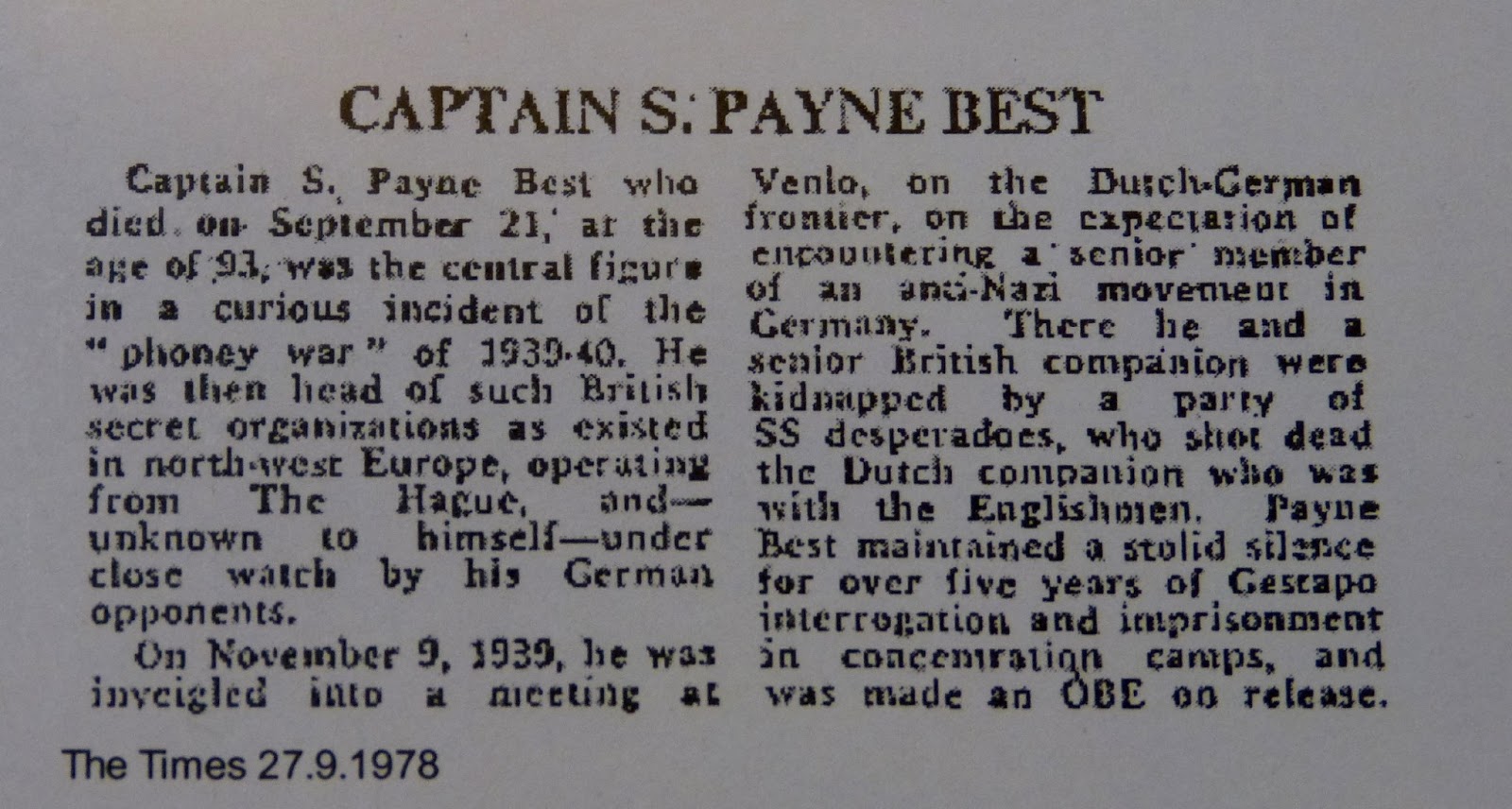

The Venlo Incident was a covert German Sicherheitsdienst (SD-Security Service) operation, in the course of which two British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) agents were abducted on the outskirts of the town of Venlo, the Netherlands, on November 9, 1939. The incident was later used by the German Nazi government to link Britain to Georg Elser’s failed assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler at the Bürgerbräukeller in Munich, Germany, on November 8, 1939, and to help justify Germany’s invasion of the Netherlands, while a neutral country, on 10 May 1940.

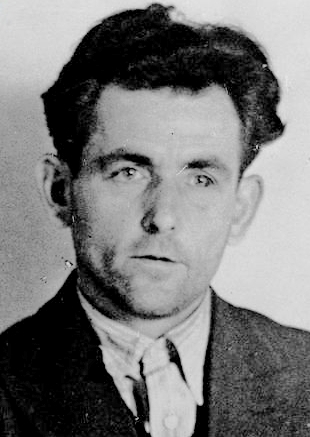

In early September 1939, a meeting was arranged between Fischer and the British SIS agent Captain Sigismund Payne Best. Best was an experienced British Army intelligence officer who worked under the cover of a businessman residing in The Hague with his Dutch wife.

Subsequent meetings included Major Richard Henry Stevens, a less-experienced intelligence operative working covertly for the British SIS as the Passport Control Officer in The Hague, Netherlands.

To assist Best and Stevens in passing through Dutch mobilised zones near the border with Germany, a young Dutch officer, Lieutenant Dirk Klop, was recruited by the Chief of the Dutch Military Intelligence, Major General van Oorschot. Klop was permitted by van Oorschot to sit in on covert meetings but not take part due to the neutrality of the Netherlands.

Fischer was brought to the early meetings where participants posing as German officers supported a plot against Hitler and were interested in establishing Allied peace terms should Hitler be deposed. When Fischer’s success in setting up the meetings with the British agents became known, Sturmbannführer (major) Walter Schellenberg of the Foreign Intelligence (Counter-Espionage) section of the Sicherheitsdienst began coming to the meetings.

Masquerading as a “Hauptmann (captain) Schämmel”, Schellenberg was at the time a trusted operative of Heinrich Himmler and was in close contact with Reinhard Heydrich during the Venlo operation.

At the last meeting between the British SIS agents and the German SD officers on Wednesday 8 November, Schellenberg promised to bring a general to the meeting on the following day. Instead, the Germans brought the talks to an abrupt end with the kidnapping of Best and Stevens.

For different Germans, the covert meetings might have meant different things. Dutch historian, Bob de Graaf wrote:

“Hitler, who was kept informed, might have hoped that sooner or later Dutch neutrality would be compromised. Himmler, continually on the outlook for a peace settlement with Britain, might have had hopes that the contacts with MI6 would lead to a compromise, whereafter the Soviet Union, in Himmler’s mind Germany’s real enemy, could be faced with confidence. To Schellenberg, the game meant gathering information about British intelligence activities in Germany. By studying the files he had become especially interested in a so-called ‘observer corps’ the British were running against the German Luftwaffe. What Schellenberg expected from the meetings were names, as many names as possible of agents working for MI6. To Heydrich, who liked intelligence games for the sake of it, the Spiel with Best and Stevens might have meant anything. But in the light of his continuous efforts to get at Canaris’ throat, he might have hoped for revelations about a connection between British officials and a German opposition, which was rooted in Wehrmacht circles”

Early on November 9, 1939, Schellenberg received orders from Heinrich Himmler to abduct the British SIS agents, Best and Stevens. German SS-Sonderkommandos (SS Special Units) under the operations command of SD man Alfred Naujocks, carried out the orders.

Best was at the wheel of his car when he drove into the car park at the Cafe Backus for the meeting planned for 4 pm with Schellenberg. Stevens was sitting beside him while Lieutenant Klop and Jan Lemmens (Best’s Dutch driver) were sitting in the back seat. Before Best had time to get out of the car, Naujock’s SD men arrived.

In a brief shootout, Klop was mortally wounded. After being handcuffed and standing against a wall, Best and Stevens, together with Jan Lemmens were bundled into the SD car. Klop was put into Best’s car and both cars were driven off over the border into Germany.

Best recalls a full body search was performed on him when they reached Düsseldorf en route to Berlin. At Düsseldorf one of the men who had taken part in the kidnapping told Best the reason for the action was to catch some Germans plotting against the Führer who was responsible for the attempt on his life the night before.

Lieutenant Dirk Klop was admitted to the Protestant Hospital in Düsseldorf. A doctor on duty recalled years later Klop was unconscious when admitted and died the same day from a gun wound to the head.

A different account (with conflicting details) of the Venlo Incident is told by Günter Peis in The Man Who Started The War, and by Walter Schellenberg in his memoirs. For instance, Best did not know that Schellenberg, still posing as Major Schämmel, was waiting at Cafe Backus at the time of the kidnapping by Naujocks and twelve SD men. When one SD man mistook him as Best, Schellenberg narrowly escaped being shot.

Before the assassination attempt at the Bürgerbräukeller in Munich on 8 November, Naujocks and his squad had been sent to Düsseldorf to support Schellenberg. Even before his private train had returned from Munich to Berlin, Hitler ordered the British SIS officers in the Netherlands to be brought to Berlin for questioning. Himmler issued the order to Schellenberg early in the morning on 9 November.

Though Georg Elser, a suspect being interrogated in Munich by the Gestapo, insisted he had acted alone, Hitler recognized the propaganda value of the assassination attempt as a means to incite German public resentment against Great Britain.

On November 21st, Hitler declared he had incontrovertible proof that the British Secret Service was behind the Munich bombing and that two British agents had been arrested near the Dutch border. The next day German newspapers carried the story. On the front page of Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, there were pictures of the conspirators named Georg Elser, “Kaptain Stevens” and “Mr. Best.”

Years later Walter Schellenberg recalled in his memoirs:

“He (Hitler) began to issue detailed directives on the handling of the case to Himmler, Heydrich, and me and gave releases to the press. To my dismay, he became increasingly convinced that the attempt on his life had been the work of British Intelligence and that Best and Stevens, working together with Otto Strasser, were the real organizers of this crime.

Meanwhile, a carpenter by the name of Elser had been arrested while trying to escape over the Swiss border. The circumstantial evidence against him was very strong, and finally, he confessed. He had built an explosive mechanism into one of the wooden pillars of the Beer Cellar. It consisted of an ingeniously worked alarm clock that could run for three days and set off the explosive charge at any given time during that period. Elser stated that he had first undertaken the scheme entirely on his initiative, but that later on two other persons had helped him and had promised to provide him with refuge abroad afterward. He insisted, however, that the identity of neither of them was known to him…I thought it possible that the “Black Front” organization of Otto Strasser might have something to do with the matter and that the British Secret Service might also be involved. But to connect Best and Stevens to the Beer Cellar attempt on Hitler’s life seemed to me quite ridiculous. Nevertheless, that was exactly what was in Hitler’s mind. He announced to the press that Elser and the officers of the British Secret Service would be tried together. In high places there was talk of a great public trial, to be staged with the full orchestra of the propaganda machine, for the benefit of the German people. I tried to think of the best way to prevent this lunacy.”

The Nazi press reported that the Gestapo had tricked the British Secret Service into carrying on radio contact for 21 days after Best and Stevens were abducted using the radio transmitter given to them. Himmler is accredited to quipping, “After a while, it became boring to converse with such arrogant and foolish people.”

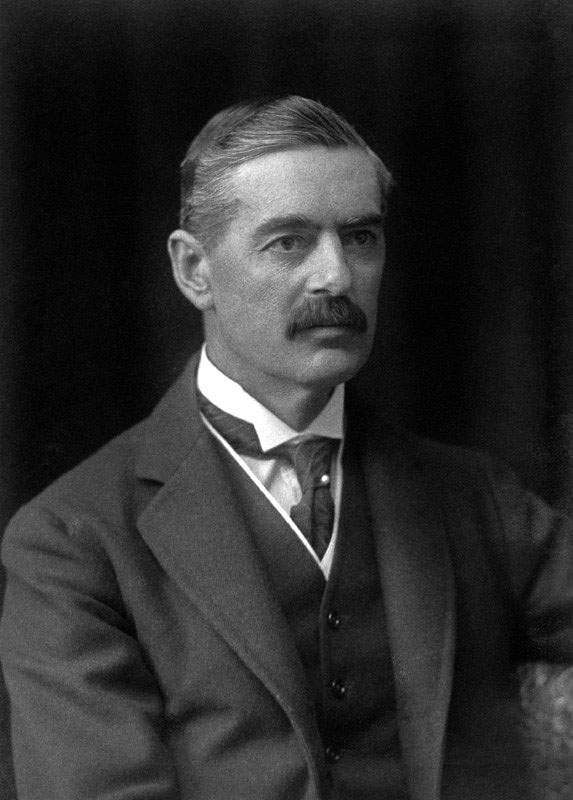

The British Foreign Office believed Himmler was involved in the secret Anglo-German contact of autumn 1939, and that the discussions, involving Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, and the Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, were bona fide peace negotiations.

The damage inflicted on Britain’s espionage network in Europe caused a new Prime Minister, Winston Churchill to start a spy and sabotage agency, the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in 1940.

The Venlo Incident exposed the fact that the Chamberlain government was still seeking to do a deal with Germany while exhorting the nation to a supreme war effort.

Hitler used the Venlo Incident to claim The Netherlands had violated its neutrality. The presence of the Dutch agent Klop, whose signature on his papers was gratefully misused by the Germans, provided sufficient proof of cooperation between British and Dutch secret services, and justify an invasion of The Netherlands by Germany in May 1940.

Alfred Naujocks was awarded the Iron Cross by Hitler the day after the kidnapping. Walter Schellenberg gave evidence against other Nazis at the Nuremberg Trials. He died from a heart attack in 1952 at the age of 42.

After interrogation at the Gestapo Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse headquarters in Berlin, Best and Stevens were sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Both were held in isolation in the T-shaped building reserved for protected prisoners of the Gestapo.

While at Sachsenhausen Best claimed he corresponded via secret letters with another protected prisoner Georg Elser.

In January 1941 Stevens was moved from Sachsenhausen to the bunker at Dachau concentration camp where he remained until evacuated with Best and other protected prisoners in April 1945.

In February 1945, Best was transferred briefly to Buchenwald concentration camp and then to the ‘bunker’ at Dachau concentration camp on 9 April 1945. Coincidentally, on the same day Georg Elser was killed at Dachau.

On April 24, 1945, Best and Stevens left Dachau with 140 other protected ‘high-profile’ prisoners in a convoy bound for South Tyrol. At the lakeside Prags Wildbad Hotel near Niederdorf, South Tyrol, they were liberated by the advancing US Army on 4 May 1945.

Timeline of the Venlo Incident

Early September 1939

- Britain has just declared war on Germany.

- MI6 (SIS) seeks contacts with possible anti-Hitler elements inside the German military and intelligence.

- German SD agent Walter Schellenberg begins a deception operation, pretending to represent a group of high-ranking German officers plotting against Hitler.

September–October 1939

- MI6 officers Sigismund Payne Best and Richard Stevens hold several clandestine meetings on the Dutch–German border near Venlo.

- The Dutch government allows limited intelligence collaboration but insists meetings stay on Dutch territory to maintain neutrality.

- “German plotters” provide enough credible-sounding information to keep MI6 engaged, feeding hopes of a coup in Berlin.

7 November 1939

- The “resisters” warn MI6 agents that Gestapo pressure is increasing and urge a quick meeting.

- In reality, German operatives prepare an abduction plan.

8 November 1939

- The Bürgerbräukeller bombing: Georg Elser attempts to assassinate Hitler in Munich.

- Hitler survives because he leaves the beer hall earlier than usual.

- Within hours, Nazi propaganda tries to tie the bombing to “British agents,” though this is fabricated.

9 November 1939 – The Abduction

- Best, Stevens, and Dutch officer Lt. Dirk Klop go to a café on the Dutch border near Venlo for another meeting.

- A German commando unit crosses the border in violation of Dutch sovereignty.

- They open fire, killing Lt. Klop, and kidnap Best and Stevens, dragging them into Germany.

10–15 November 1939

- Germany announces publicly:

- Britain was conducting espionage in the “neutral” Netherlands.

- The Venlo incident proves British involvement in the Munich bombing (totally fabricated).

- The Netherlands protests the border violation but is in no position to resist.

1940–1945

- Best and Stevens are imprisoned in Germany for nearly the entire war.

- Their captivity is relatively harsh at first, later eased after diplomatic pressure.

MI6 Operations in the Netherlands (Pre-WWII to 1940)

A structured intelligence profile

1. Strategic Importance of the Netherlands

Before WWII, the Netherlands sat in a critical geopolitical position:

- Directly bordering Germany.

- Close to the Ruhr industrial centers.

- Officially neutral, but with quiet sympathy toward Britain and France.

This made it:

- A perfect listening post on Germany.

- A safe(ish) place for SIS to run covert meetings and communications.

- A transit point for couriers, defectors, and political dissidents.

Because the Dutch insisted on neutrality, SIS had to operate discreetly, often under non-official cover.

2. MI6 Organizational Presence

A. SIS Station in The Hague (“Passport Control Office”)

Like in many European cities, MI6 used the British Passport Control Office (PCO) as a cover for intelligence operations.

- Head of station:

Major Richard Henry Stevens (front-line SIS officer, but relatively inexperienced operationally). - Focus:

- Gathering information on the German military.

- Contact with anti-Nazi circles and dissidents.

- Maintaining relations with the Dutch intelligence service (GSIII).

- Limitations:

- Very small team (fewer than 5 operational officers).

- Overworked, with minimal vetting infrastructure.

- Limited training: MI6 had not yet evolved into the professional service it became later in the war.

B. Senior Agent in the Netherlands: Sigismund Payne Best

- Formally retired, but brought back into SIS due to his extensive prewar contacts in Germany.

- He had:

- A strong reputation with German aristocratic and nationalist circles.

- Long personal networks dating back to WWI intelligence work.

- Problem: He relied heavily on intuition and personal charm, not modern tradecraft.

Best was essentially the field operator, while Stevens handled station leadership.

3. Operational Goals (1938–1939)

1. Monitoring German Military Activity

- Watching troop movements across the border.

- Recruiting sources among businessmen, border officials, and travelers.

2. Contacting Possible Anti-Hitler Resistance

This was the most ambitious SIS activity:

- Britain knew discontent existed in parts of the Wehrmacht and German intelligence.

- SIS was eager to encourage or at least explore possibilities of a coup.

- Best served as the bridge to these alleged dissident officers.

This became the main vulnerability leading to the Venlo Incident.

3. Evacuation and exfiltration

- Helping refugees, informants, and endangered individuals escape Germany.

- Facilitating communication with exiled Germans, Austrians, and Czechs.

4. Liaison with Dutch Intelligence

- The Dutch allowed selective cooperation but insisted:

- Operations remain low-key.

- No activities violate neutrality.

- Lt. Dirk Klop was assigned as a liaison officer — tragically, he would be killed in the Venlo ambush.

4. Tradecraft Weaknesses

1. Over-reliance on border meetings

Meetings were often held in cafés right near the German border. Easy for the SD to observe and exploit.

2. Weak source verification

The “German dissident officers” were never properly vetted. They provided:

- Some accurate public information (to appear credible).

- Huge promises (high-level conspirators, anti-Hitler plots).

MI6 officers were too eager to believe in a German resistance.

3. Operational security failures

- Stevens carried sensitive documents, notebooks, and code materials with him to the final meeting—a major security breach.

- Best openly discussed British intelligence interests with the “resisters.”

This gave the Germans valuable insight into SIS priorities and limitations.

5. The Impact of Dutch Neutrality

Dutch constraints meant:

- No surveillance on the German “resisters” by Dutch police.

- No ability for MI6 to operate freely.

- SIS could not arrest suspicious visitors or run aggressive counterintelligence.

The Germans exploited these soft borders and the Dutch desire to avoid escalation.

6. Assessment: Why MI6 Was Vulnerable

Historians cite several structural weaknesses:

1. Underfunded, understaffed SIS

In the 1930s, Britain did not invest heavily in foreign intelligence.

SIS had:

- Too few officers.

- Limited training.

- No centralized vetting or analysis system.

2. Desperation for anti-Hitler allies

MI6 wanted internal German resistance to be real.

This made them overlook red flags.

3. Schellenberg’s skillful deception

The Germans were:

- Well-prepared.

- Professionally trained.

- Backed by Gestapo and SD intelligence.

In contrast, MI6 officers in the Netherlands relied on prewar habits and gentleman-spy traditions.

4. Structural problems in MI6 headquarters

London:

- Encouraged contact with supposed conspirators.

- Failed to insist on rigorous checks.

- Pressured the field officers to pursue the “coup” link.

7. Aftermath for MI6 in the Netherlands

Post-incident (late 1939–May 1940)

- MI6 reduced overt meetings.

- Relations with Dutch intelligence became strained.

- The Dutch government feared Germany would use the incident as a pretext (which they did).

- SIS evacuated the Netherlands when Germany invaded on 10 May 1940.

Institutional impact

The Venlo disaster led to:

- Improvement in MI6 training.

- Better source vetting procedures.

- Enhanced operational security (OPSEC).

- Greater caution about “too good to be true” sources—especially from inside enemy regimes.

SOURCES

https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/9910937623102121

https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.7312/klef91718-004/pdf

https://www.tracesofwar.com/articles/2452/Venlo-incident.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venlo_incident

Please support us so we can continue our important work.

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment