Simon Wiesenthal was born on December 31, 1908, in Buczacz, a town then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (today in western Ukraine). He was the eldest of four children in a Jewish family. His father was a teacher, and Wiesenthal grew up in an environment that valued education and community involvement. He pursued studies in architecture at the Technical University in Prague and later at the Polytechnic Institute in Lviv, reflecting his initial ambition to pursue a professional career in engineering.

The political upheavals of the 1930s, including the rise of Nazism, profoundly affected his life. In 1939, after the outbreak of World War II and the German and Soviet invasions of Poland, Wiesenthal’s homeland fell under German occupation. Jewish families, including Wiesenthal’s, faced persecution, forced ghettoization, and the threat of mass executions.

Holocaust Survival (1941–1945)

In 1941, Wiesenthal and his family were deported to the Janowska concentration camp near Lviv. His parents and other relatives were murdered, while Simon endured forced labor, disease, and near-starvation. He was later transferred to several other camps, including Kraków-Płaszów, which was under the command of the infamous Amon Göth, and eventually to Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria.

Wiesenthal survived the Holocaust largely through resourcefulness, sheer endurance, and, at times, the aid of sympathetic fellow prisoners. Liberation came in May 1945, but the trauma and the loss of his family shaped his determination to ensure that Nazi perpetrators would not evade justice.

Immediate Postwar Efforts (1945–1947)

After liberation, Wiesenthal initially worked to assist fellow survivors in displaced persons (DP) camps. Settling in Linz, Austria, he began collecting information on Nazi officials and collaborators. He meticulously documented names, ranks, locations, and activities, recognizing that many war criminals were reintegrating into society undetected.

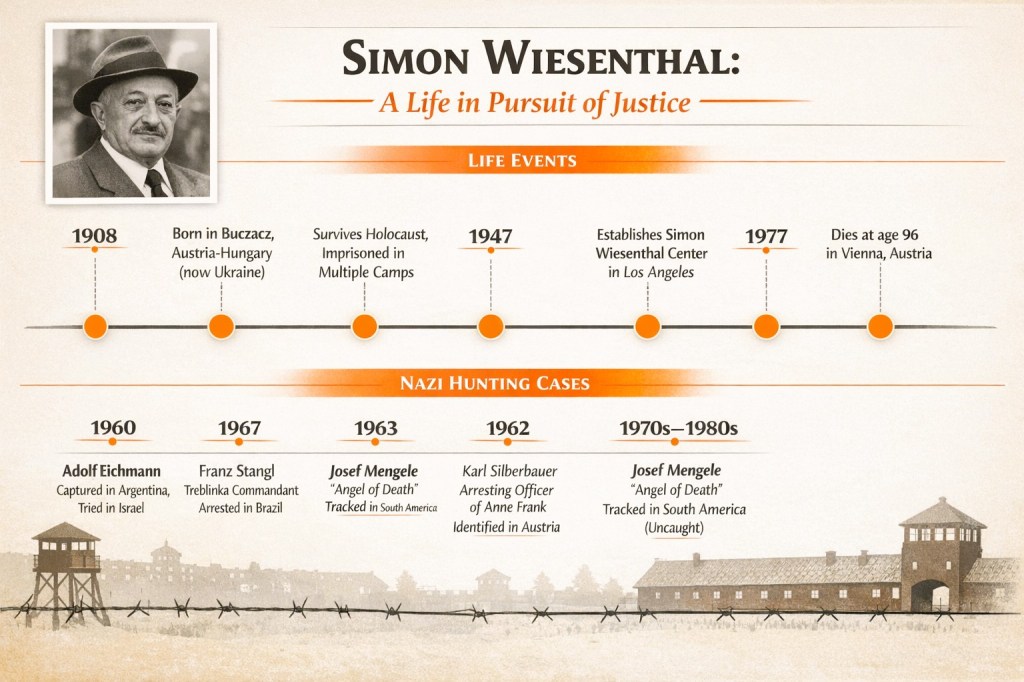

In 1947, Wiesenthal founded the Jewish Documentation Center in Vienna. The center became a hub for investigating Nazi war crimes, preserving documentation, and assisting international tribunals and national courts in prosecuting those responsible for genocide.

Major Cases and Investigations (1947–1960s)

Wiesenthal’s work led to the identification and capture of numerous Nazi criminals:

Adolf Eichmann (1906–1962): Although Israeli Mossad agents eventually captured Eichmann in Argentina in 1960, Wiesenthal’s research played a crucial role in tracking Eichmann’s postwar whereabouts. Eichmann, a key architect of the “Final Solution,” was tried in Jerusalem and executed in 1962.

Franz Stangl (1908–1971): Commandant of Treblinka extermination camp, Stangl was located and arrested in Brazil in 1967. Wiesenthal’s documentation helped authorities identify his identity and crimes. Stangl was extradited to Germany and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Karl Silberbauer (1911–1972): The Austrian SS officer responsible for arresting Anne Frank and her family in Amsterdam was identified by Wiesenthal decades later, highlighting Wiesenthal’s skill in connecting past crimes to present identities.

Josef Mengele (1911–1979): While Wiesenthal was unable to capture the infamous “Angel of Death” of Auschwitz, he tirelessly gathered information about Mengele’s movements, contributing to international awareness and historical documentation.

Wiesenthal’s approach was meticulous. He often relied on archival research, survivor testimonies, and intelligence networks to locate former Nazis who had assumed false identities or fled abroad. His efforts demonstrated the importance of documentation and persistence in pursuing justice.

Public Advocacy and the Simon Wiesenthal Center (1970s–1990s)

By the 1970s, Wiesenthal had become an internationally recognized figure. He traveled extensively, lecturing on Holocaust remembrance and warning against the resurgence of anti-Semitism and extremism. In 1977, the Simon Wiesenthal Center was formally established in Los Angeles, functioning as both an educational institution and an advocacy organization. The center focused on human rights education, Holocaust documentation, and promoting international legal standards to prevent crimes against humanity.

During this period, Wiesenthal continued to track war criminals and collaborate with governments worldwide. His work emphasized moral accountability and the principle that perpetrators of genocide could not escape justice, regardless of the passage of time.

Wiesenthal’s methods and claims were sometimes contested. Critics argued that some of his alleged identifications were inaccurate or overstated, and certain high-profile cases, like that of Mengele, ended without capture. Nonetheless, the overall impact of his work remains uncontested: Wiesenthal brought global attention to the pursuit of justice for Holocaust victims and institutionalized the study and documentation of Nazi crimes.

Recognition and Honors

Over his lifetime, Wiesenthal received numerous awards for his contributions to justice and human rights, including:

The Austrian Cross of Honor for Science and Art

The French Legion of Honor

The U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom

Recognition from Jewish communities worldwide for his dedication to remembrance and moral advocacy

His writings, including memoirs and investigative accounts, further educated generations about the Holocaust and the ethical imperative of accountability.

Death and Legacy (2005 and Beyond)

Simon Wiesenthal passed away on September 20, 2005, at the age of 96. By the time of his death, he had dedicated six decades to uncovering Nazi war criminals and advocating for Holocaust remembrance. His legacy endures through the Simon Wiesenthal Center, the extensive archives of his investigations, and the moral example he set for pursuing justice against crimes against humanity.

Wiesenthal’s life underscores the importance of resilience, documentation, and ethical vigilance. His relentless work ensured that countless perpetrators were brought to justice and that the horrors of the Holocaust remain an enduring lesson for humanity.

Simon Wiesenthal’s journey from survivor to globally recognized Nazi hunter reflects both the depths of human cruelty and the heights of human courage. Through painstaking research, advocacy, and moral conviction, he transformed personal tragedy into a lifelong mission for justice. His work not only brought criminals to account but also preserved the memory of millions of victims, ensuring that future generations could learn from history and uphold the principles of justice, human rights, and moral responsibility.

Cyla And Simon Wiesenthal- A remarkable Love story.

The story of Simon Wiesenthal’s marriage to Cyla Wiesenthal is as remarkable as his lifelong pursuit of justice.

Simon and Cyla married in 1936 and settled in the Polish city of Lvov, now part of Ukraine. In 1941, following the Nazi invasion, Lvov was transformed into the Jewish ghetto of Lemberg. That October, the Wiesenthals were deported to a small labor camp, where they were forced to work for a year. As the mass murder of Jews intensified, they understood that transfer to an extermination camp was only a matter of time.

Later in 1941, they were sent to the Janowska concentration camp and assigned to work at the Eastern Railway Repair Works. Simon was compelled to paint swastikas and other markings on captured Soviet locomotives, while Cyla polished brass and nickel components. Using information he provided about the railways, Simon secured false identity papers for Cyla through a contact in the Armia Krajowa, the Polish underground resistance. In early 1943, the resistance smuggled Cyla out of the camp and supplied her with a forged Christian identity.

Cyla was hidden in Lublin, more than 200 kilometers to the north. In June 1943, when the Gestapo began arresting suspicious women in the area, she returned to Lemberg in a desperate attempt to find Simon. After hiding for two days in a train station cloakroom, she briefly managed to contact him. Once again, Simon relied on resistance networks, this time arranging shelter for her in Warsaw.

In 1944, Simon attempted suicide but survived. When the Armia Krajowa informed Cyla of his actions, critical details were lost, and she came to believe he had died. Simon, meanwhile, was transferred to another camp, where he met a man who had lived on the same Warsaw street as Cyla. The man told him that the entire street had been destroyed by Nazi flamethrower units and that no one had survived. When Simon was liberated in May 1945, he contacted the Red Cross, which confirmed—incorrectly—that his wife was dead.

She was not. Cyla had been arrested in Warsaw and sent to a camp, from which British forces liberated her a month before American troops freed Simon. Each believed the other had perished until Cyla encountered a mutual acquaintance in Krakow. Shocked to see her alive, he said, “I’ve just received a letter from your husband asking me to help locate your body.” Even then, they faced another obstacle: Simon was in the American occupation zone, while Cyla was in the Soviet zone.

Simon hired a man named Felix Weissberg to smuggle Cyla across the border. Weissberg proved wildly incompetent. He destroyed her papers en route to Krakow and then forgot her address. His solution was to post a notice on a bulletin board: “Would Cyla Wiesenthal please contact Felix Weissberg, who will take her to her husband in Linz.”

Three women responded, all claiming to be Cyla Wiesenthal. Unable to transport all three with forged documents, Weissberg interviewed them and made a guess. By sheer luck, he chose correctly. Simon and Cyla were finally reunited and quickly began rebuilding their lives. Their daughter was born nine months later.

Simon Wiesenthal and his wife Cyla were later photographed in Amsterdam with Queen Juliana and her husband, Prince Bernhard.

On 18 December, 2022 I had the privilege to interview Racheli Kreisberg, the granddaughter of Simon Wiesenthal.

In the interview with Racheli, we briefly discussed her grandfather but focused more on her work for The Simon Wiesenthal Genealogy Geolocation Initiative (SWIGGI). It links genealogy and geolocation data in a novel way. They currently have the country of the Netherlands, the cities Lodz and Vienna and the Shtetls Skala Podolska, Nadworna and Solotwina. SWIGGI shows all the residents of a given house and links residents to their family trees. Simon Wiesenthal’s Holocaust Memorial pages are developed for Holocaust victims.

sources

https://simonwiesenthal-galicia-ai.com/swiggi/intro-swiggi.php

https://wiesenthal.org/about/about-simon-wiesenthal/quotes.html

https://penthouse.com/legacy/simon-wiesenthal/

Leave a comment