In the shadowy world of espionage, few cases rival the scale, audacity, and impact of the Duquesne Spy Ring. Operating in the United States during the early years of World War II, this German intelligence network sought to gather military, industrial, and strategic information critical to the Nazi war effort. Its exposure and dismantling by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 1941 remains one of the most significant counterintelligence victories in U.S. history.

By the late 1930s, Europe was sliding rapidly toward global conflict. Nazi Germany, anticipating eventual confrontation with the United States, invested heavily in foreign intelligence operations. Although the U.S. was officially neutral until December 1941, Germany recognized its industrial capacity and strategic importance as a decisive factor in the war’s outcome.

The United States, meanwhile, was ill-prepared for large-scale counterespionage. Intelligence agencies were fragmented, and federal law enforcement was still developing modern surveillance and investigative capabilities. This vulnerability made the country fertile ground for foreign intelligence services—until the FBI, under J. Edgar Hoover, made counterespionage a strategic priority.

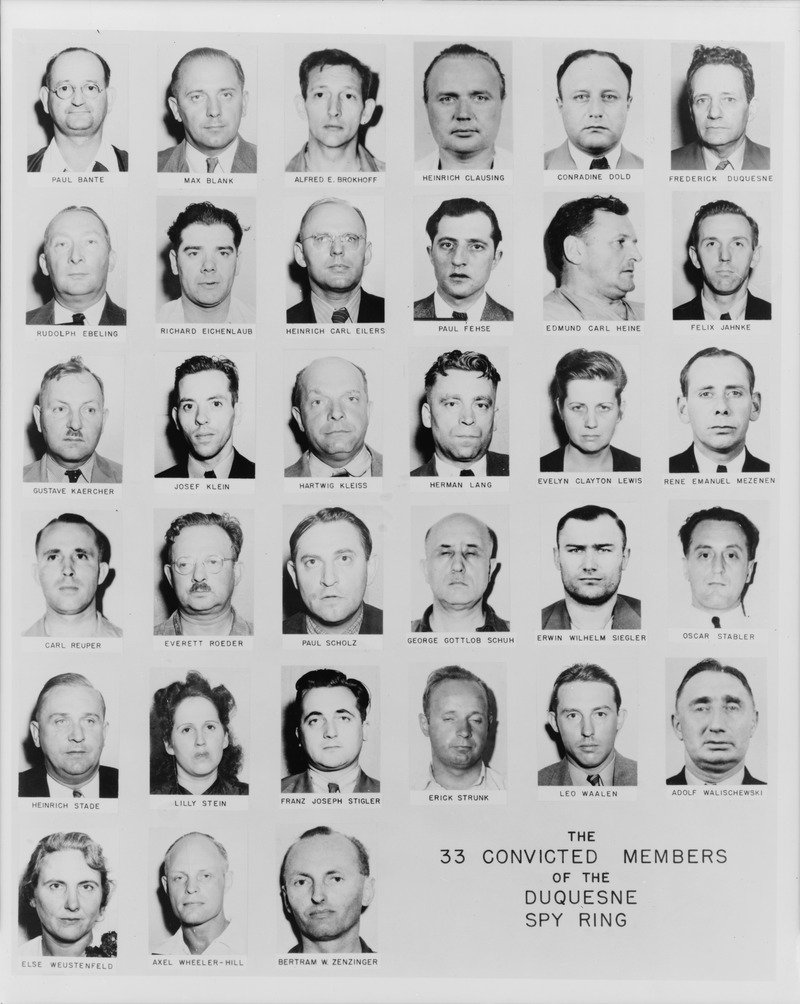

The Duquesne spy ring was the largest espionage operation in U.S. history to result in convictions. Operating within the United States during World War II, the German-led network was directed by Frederick Joubert Duquesne, a South African–born operative who became a naturalized American citizen in December 1913.

The ring was established to gather intelligence that could be exploited if the United States entered the war. Its mission included identifying vulnerabilities in American military forces and preparedness, as well as exploring methods to undermine national stability and morale. Members of the ring transmitted information related to domestic terrorism, sabotage, and both industrial and military espionage.

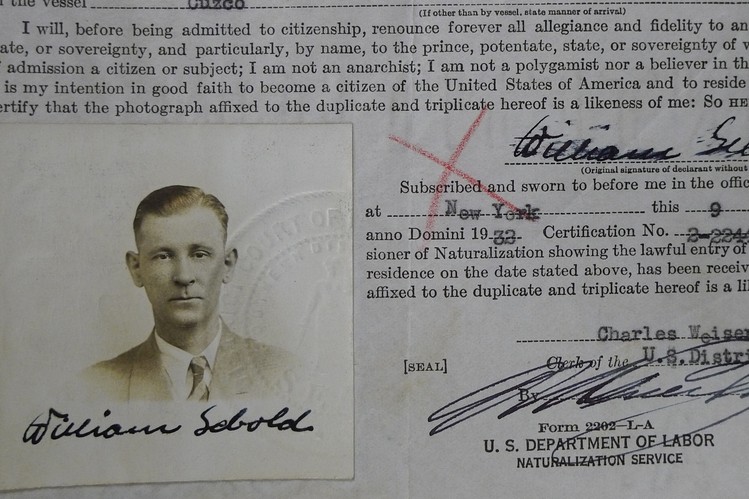

The operation was exposed when William Sebold, a German native who had served in the Imperial German Army during World War I, immigrated to the United States and became a naturalized citizen on February 10, 1936.

While living in the United States—and for a period in South Africa—Sebold worked in industrial and aircraft manufacturing plants, gaining technical experience of interest to German intelligence. In February 1939, he returned to Germany to visit his ailing mother, where he was approached by a Gestapo agent who informed him that he would be contacted again. Sebold later obtained employment in Mülheim, and seven months afterward was visited by a man who introduced himself as Dr. Gassner.

Gassner questioned Sebold extensively about his knowledge of military aircraft and equipment and then proposed that Sebold return to the United States to act as a spy for Germany. Subsequent visits by Gassner and another individual—later identified as Major Nikolaus Ritter of the German Secret Police—culminated in Sebold’s reluctant agreement to cooperate, motivated largely by threats of reprisals against his family in Germany.

Ritter was the Abwehr’s chief of espionage operations against the United States and Britain and was determined to establish a comprehensive intelligence apparatus before American entry into the war.

Following Gassner’s visit, Sebold’s passport was stolen, prompting him to seek a replacement at the U.S. Consulate. While there, he discreetly informed consular officials that he had been recruited to spy on the United States and expressed his desire instead to serve as a double agent for the U.S. government. German intelligence subsequently sent him to Hamburg for espionage training, where he was instructed in microphotography and the preparation of coded messages. He was provided with five microphotographs containing intelligence to be transmitted to Germany and was directed to retain two while delivering the remaining three to designated operatives, including Frederick Joubert Duquesne.

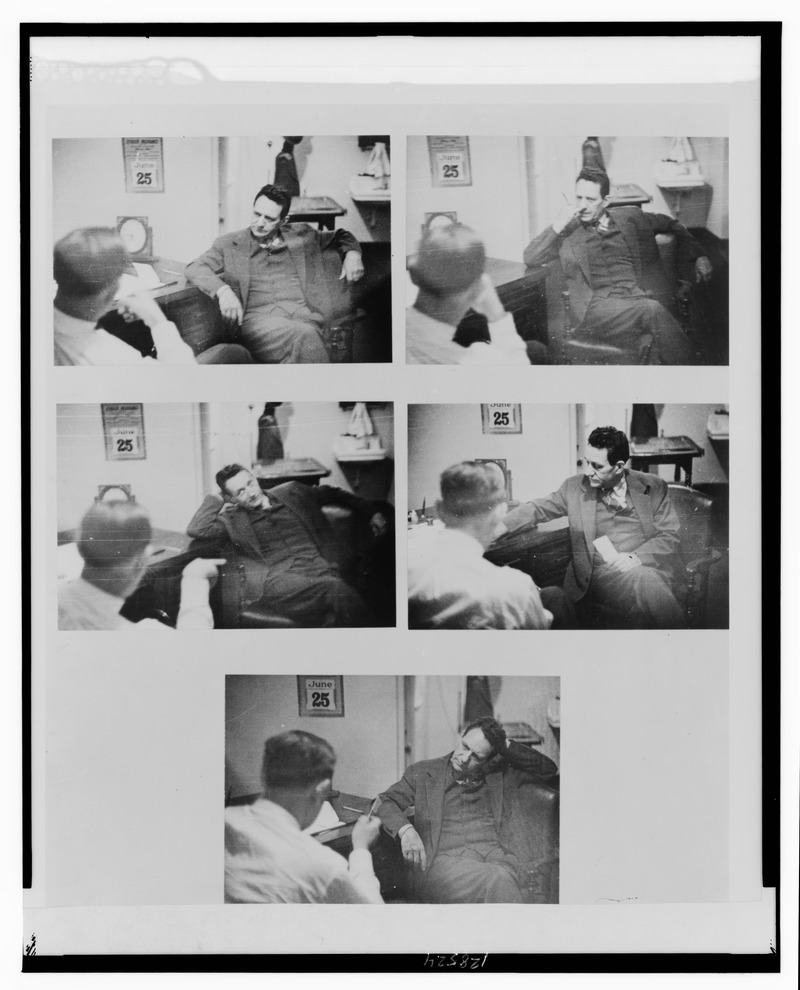

Sebold returned to the United States via Genoa, Italy, arriving in New York City in February 1940 under the alias Harry Sawyer. The Federal Bureau of Investigation had been informed of his role and assisted him in securing both a residence and an office. Operating under the cover of a diesel engineering consultant, Sebold worked from an office deliberately selected to facilitate constant FBI surveillance; the space was equipped with hidden microphones and two-way mirrors.

The FBI also established a sophisticated shortwave radio transmission system to maintain contact with German-operated radio stations. This system became the primary channel of communication between the spy network and its German handlers. Over a period of sixteen months, FBI agents—posing as Sebold—sent approximately 300 carefully crafted messages to Germany and received about 200 in return.

Sebold met repeatedly with members of the espionage network in his office, all of which was recorded by the FBI. He held several meetings with Duquesne, who provided information concerning potential acts of sabotage at industrial facilities, as well as plans for the development of a new bomb allegedly stolen from a DuPont plant in Wilmington, Delaware. Another member of the ring, Paul Bante, discussed plans to bomb various locations and supplied explosive materials in furtherance of those objectives.te and detonation caps to Sebold.

Through Sebold’s undercover work, the FBI gathered sufficient evidence to arrest and convict all members of the spy ring before they could carry out any of their planned operations. Fourteen members pleaded guilty, while the remaining nineteen were found guilty of espionage on December 13, 1941. On January 2, 1942, the group was sentenced to a total of 300 years in prison. A senior German intelligence official later acknowledged that Sebold’s activities had dealt a fatal blow to German espionage efforts in the United States, and J. Edgar Hoover described the operation as the greatest spy roundup in U.S. history.

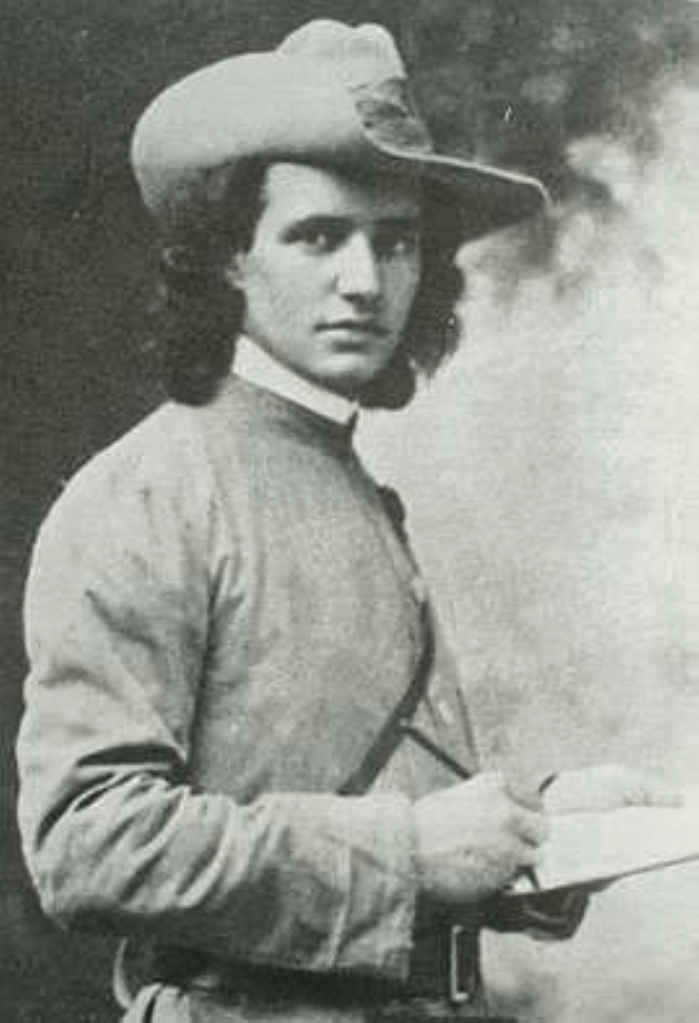

Although history largely remembers Fritz Joubert Duquesne (1877–1956) as a German spy during World War II, his roots were far from Germany. Duquesne was a Boer, a descendant of Dutch settlers who had carved out a life on the frontier of colonial South Africa. The Boers were renowned for their resilience, independence, and martial skill—traits that Duquesne embodied throughout his life.

His early years were marked by both tragedy and violence. At just 12 years old, Duquesne killed his first man: a Zulu attacker who had assaulted his mother. Armed only with a spear, the young boy survived a brutal confrontation that would foreshadow his future as a hardened combatant. The South African veld—dry, open, and unforgiving—became the setting for further deadly encounters. During a family escape from an attacking force of Zulu warriors (Impi), Duquesne killed several more attackers, but not without immense personal loss. He witnessed the deaths of his uncle, wife, and infant child, cementing a profound familiarity with death and survival at an early age.

These experiences, while horrific, forged a sense of self-reliance and tactical cunning that would later serve him in espionage. After these violent events, Duquesne was sent to study in England, stepping briefly away from the veld but carrying with him a life steeped in conflict and danger. This early exposure to combat, loss, and strategy would shape not only his personal character but also the methods and audacity of his later intelligence operations.

The Duquesne Spy Ring stands as a landmark case in American intelligence history. It revealed both the sophistication of foreign espionage efforts and the growing effectiveness of U.S. counterintelligence. More than a dramatic story of spies and double agents, it was a defining moment that reshaped national security practices in the United States.

In dismantling the largest spy ring ever uncovered on American soil, the FBI not only neutralized an immediate threat but also signaled that the United States had entered a new era of vigilance—one in which intelligence would play a central role in global conflict.

sources

https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/duquesne-spy-ring

https://www.paperlessarchives.com/duquesne.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duquesne_Spy_Ring

https://www.beachesofnormandy.com/articles/Superspy_killed_first_at_age_12/?id=e395ea628e

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment