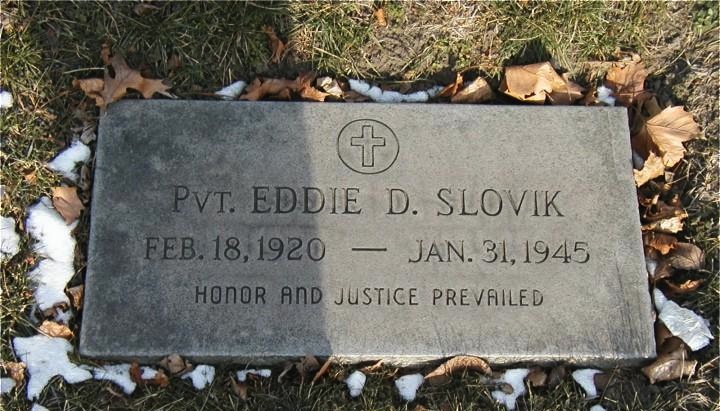

Eddie Slovik was executed on January 31, 1945, becoming the only American soldier put to death for desertion since the Civil War. Of approximately 40,000 U.S. service members who deserted during World War II, only several thousand were court-martialed. Forty-nine received death sentences, but Slovik was the only one whose sentence was executed.

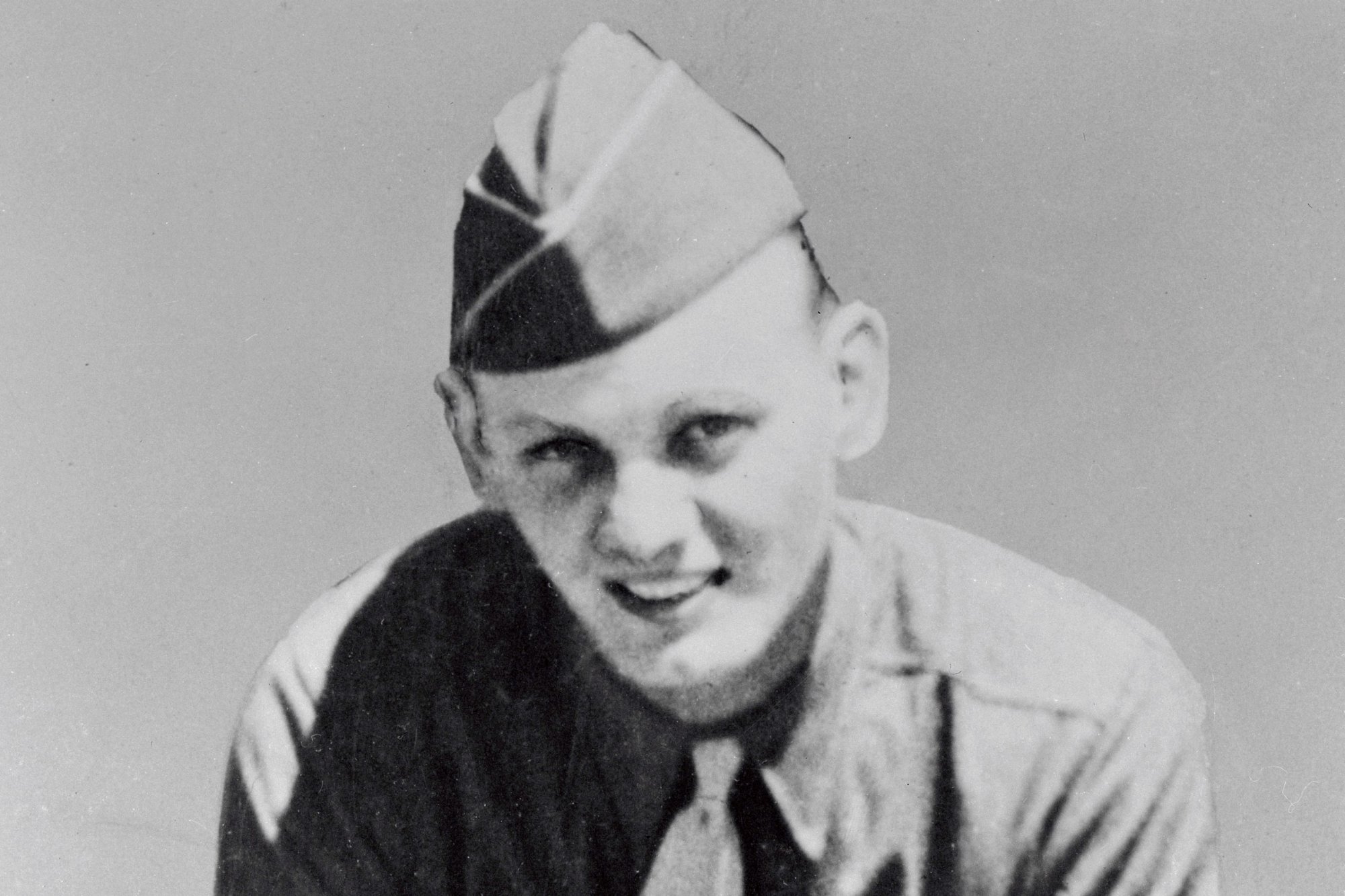

Private Eddie Slovik was a draftee. Initially classified 4-F because of a criminal record for auto theft, he was later reclassified 1-A when the Army lowered standards to meet rising manpower demands. In January 1944, he was trained as a rifleman — an assignment he disliked, as he was deeply uncomfortable with weapons.

In August 1944, Slovik was sent to France as a replacement for the 28th Infantry Division, a unit that had already suffered heavy casualties in fighting across France and Germany. Replacement troops were often viewed with limited confidence by frontline officers. While en route to join his unit, Slovik and another soldier became separated amid the confusion of combat operations and attached themselves to a Canadian unit.

They remained with the Canadians until October 5, when they were turned over to American military police and rejoined the 28th Division, then stationed near Elsenborn, Belgium. No disciplinary action was taken at that time, as newly arrived replacements becoming lost during initial movement to the front was not uncommon.

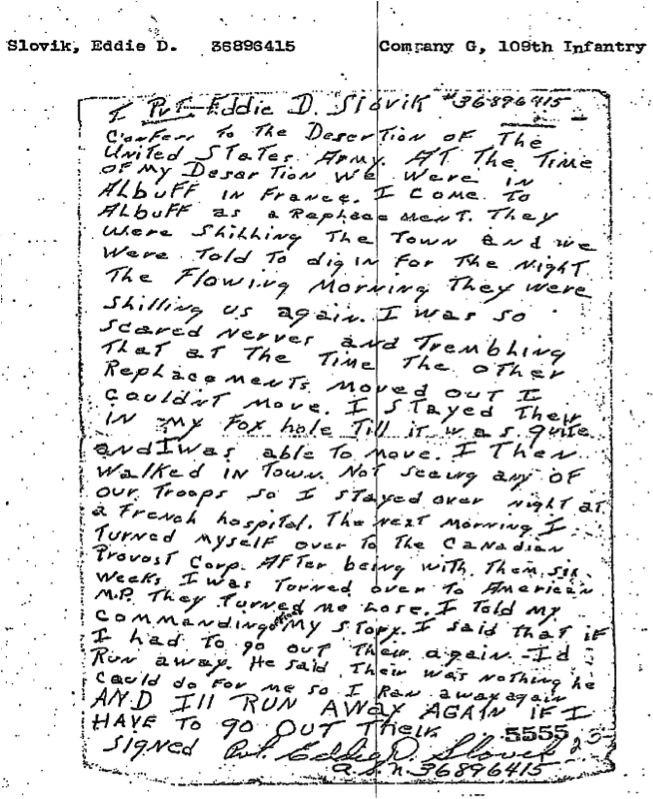

The following day, however, Slovik told his unit that he was “too scared and too nervous” to serve as a rifleman and said he would run away if ordered into combat. His statement was disregarded, and he left the unit. He returned the next day and submitted a written confession of desertion, again stating that he would flee if forced to fight. A regimental officer warned him to withdraw the statement, emphasizing the severity of the consequences, but Slovik refused. He was then placed in confinement.

The 28th Infantry Division had experienced numerous cases of soldiers deliberately wounding themselves or deserting in hopes that imprisonment might spare them from frontline combat. Against this backdrop, a division legal officer offered Slovik an alternative: return immediately to duty and the court-martial would be dropped. Slovik refused.

He was tried for desertion on November 11, 1944, and convicted in less than two hours. The nine-member court-martial panel unanimously sentenced him to death, ordering that he “be shot to death with musketry.”

Slovik’s appeal was denied. Reviewing authorities concluded that he had “directly challenged the authority” of the United States and that “future discipline depends upon a resolute reply to this challenge.” Determined to make an example of him, the Army allowed the sentence to stand.

A final appeal reached General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander. The request came at a moment when mercy was in short supply. The Battle of the Bulge was underway in the Ardennes, producing thousands of American casualties and widespread strain on morale and discipline. Eisenhower upheld the sentence.

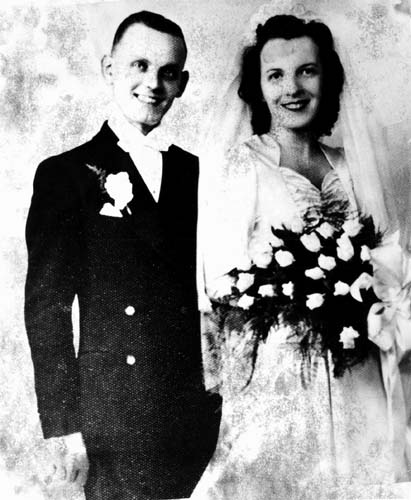

Afterward, Slovik’s widow described him as “the unluckiest poor kid who ever lived.”

The execution was carried out in France on January 31, 1945. Beforehand, Slovik said:

“They’re not shooting me for deserting the United States Army — thousands of guys have done that. They just need to make an example out of somebody, and I’m it because I’m an ex-con. I used to steal things when I was a kid, and that’s what they’re shooting me for. They’re shooting me for the bread and chewing gum I stole when I was 12 years old.”

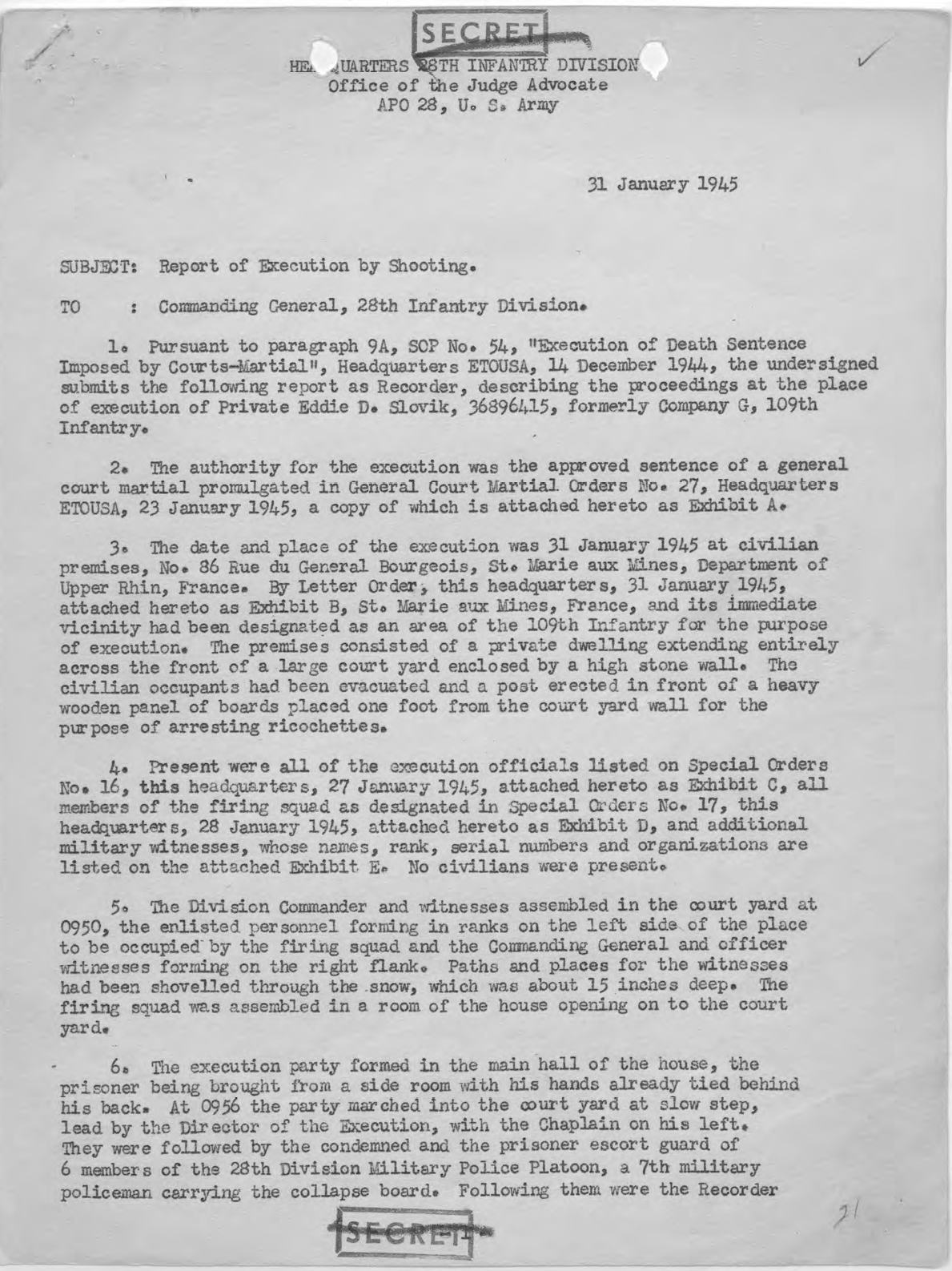

On the morning of the execution, soldiers strapped him to a post using web belts. The attending chaplain said, “Eddie, when you get up there, say a little prayer for me.” Slovik replied, “Okay, Father. I’ll pray that you don’t follow me too soon.”

A twelve-man firing squad carried out the sentence, firing a volley that struck him with eleven bullets. Slovik was pronounced dead shortly afterward in eastern France. Many of the soldiers present reportedly believed the punishment was justified, seeing the execution as a necessary example to maintain discipline during a brutal phase of the war.

In 1960, Frank Sinatra announced plans to produce a film titled The Execution of Private Slovik, written by blacklisted Hollywood Ten screenwriter Albert Maltz. The announcement sparked widespread outrage, and Sinatra was accused of being a Communist sympathizer. At the time, Sinatra was campaigning for John F. Kennedy, and the Kennedy team, concerned about potential political fallout, ultimately persuaded him to cancel the project.

Earlier, Slovik’s story had been chronicled in William Bradford Huie’s 1954 book. Two decades later, in 1974, the book was adapted into a television movie of the same name, starring Martin Sheen.

The military service record of Slovik, which is now a public archival record available from the Military Personnel Records Center, provides a detailed account of the actual execution of Slovik which took place in 1945 and it was upon this that most of the film was based. Some dramatic license occurs, including during the execution. There is no evidence, for example, that the priest attending Slovik’s execution shouted “Give it another volley if you like it so much” after the doctor indicated Slovik was still alive.

In addition, the 1963 war film The Victors includes a scene featuring the execution of a deserter clearly inspired by Slovik.

Kurt Vonnegut mentions Slovik’s execution in his novel Slaughterhouse-Five.

Vonnegut also wrote a companion libretto to Igor Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du soldat (A Soldier’s Tale), which tells Slovik’s story.

Slovik also appears in Nick Arvin’s 2005 novel Articles of War, in which the fictional protagonist, Private George (Heck) Tilson, is one of the members of Slovik’s firing squad.

sources

https://www.americanheritage.com/example-private-slovik

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eddie_Slovik

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment