Last year, when I visited Dachau, we had an Irish guide. He was knowledgeable about Dachau, but I disagreed with him on one thing he said. To my own surprise, I didn’t give him a history lesson. I decided to let it go because my primary purpose there was to gain some understanding of Dachau. The thing he said was that it wasn’t the British or the Americans who won the war but the Soviets.

The tour guide is not alone in that opinion; several historians share this point of view. However, I don’t think it is a correct assessment. I believe it can even be argued that the Soviets prolonged the war. Between the start of World War II on September 3, 1939, and June 1941, the Nazis and the Soviets were allies. Even today, many of Russia’s World War II monuments list the years 1941 to 1945 as the war years, conveniently overlooking the first two years when they were aggressors alongside the Nazis.

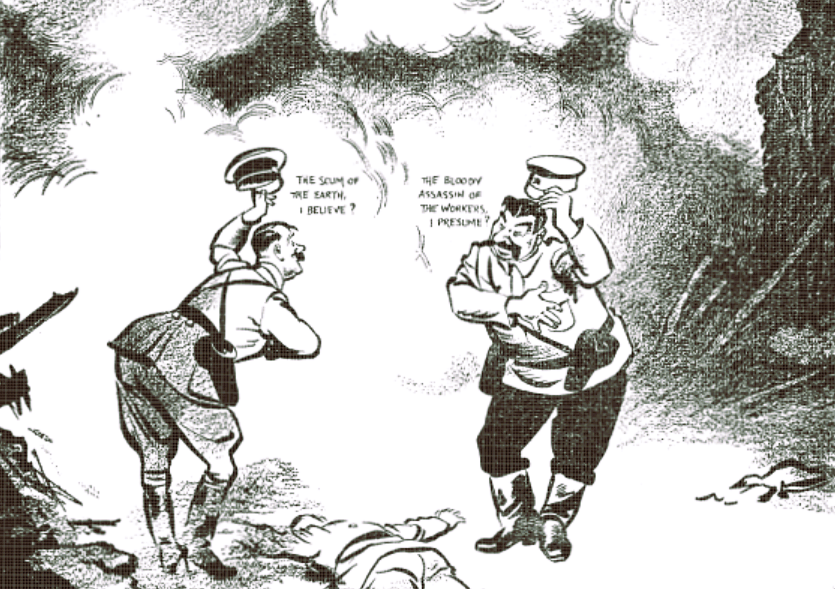

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, also known as the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, was a significant and controversial agreement signed on August 23, 1939, between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Named after the foreign ministers of the two countries, Vyacheslav Molotov of the Soviet Union and Joachim von Ribbentrop of Germany, the pact had profound implications for the course of World War II and the geopolitical landscape of Europe.

Background and Context

In the late 1930s, Europe was on the brink of war. Adolf Hitler’s aggressive expansionism had already led to the annexation of Austria in 1938 and the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia in early 1939. As Germany turned its attention toward Poland, a conflict with the Soviet Union seemed inevitable, given the two nations’ ideological opposition. The Soviet Union, led by Joseph Stalin, was wary of Nazi Germany’s intentions but also distrusted the Western powers, Britain and France, which had shown hesitancy in confronting Hitler. Stalin’s attempts to form an anti-fascist alliance with these powers had failed, leading him to explore other options to secure the Soviet Union’s borders.

Simultaneously, Hitler sought to avoid a two-front war, which had been a significant factor in Germany’s defeat in World War I. He needed to neutralize the Soviet Union to focus on his campaign in Western Europe. The convergence of these interests led to the negotiation of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, despite the ideological chasm between the Nazi regime and the communist Soviet state.

Key Provisions of the Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was officially presented as a non-aggression treaty in which both Germany and the Soviet Union pledged not to attack each other or support any third party that might do so. This aspect of the agreement was made public. It shocked the world, given the deep ideological antagonism between Nazism and communism. However, the most crucial and sinister aspect of the pact was kept secret: a protocol that divided Eastern Europe into spheres of influence.

The secret protocol outlined the partition of Poland between the two powers, with the eastern part falling under Soviet control and the western part under German control. Additionally, the protocol granted the Soviet Union influence over the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) and parts of Finland and Romania. This division of territory laid the groundwork for the eventual occupation and annexation of these regions by the Soviet Union.

Consequences and Immediate Impact

The immediate consequence of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, which marked the beginning of World War II. The Soviet Union, honoring its part of the secret protocol, invaded eastern Poland on September 17, 1939. Poland was quickly defeated and divided between Germany and the Soviet Union, with the two occupying powers consolidating their control over their respective spheres of influence.

The pact also allowed Hitler to proceed with his plans in Western Europe without fear of Soviet intervention. In the months following the pact, Germany launched a series of successful campaigns in Denmark, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands, and France. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union expanded its territory, annexing the Baltic states and parts of Romania and launching a war against Finland, known as the Winter War, in November 1939.

Historical Significance and Legacy

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact is often seen as one of the most cynical and pragmatic alliances in modern history. It was a pact between two totalitarian regimes that put aside their mutual hatred for short-term strategic gain. The agreement not only facilitated the outbreak of World War II but also led to immense suffering in Eastern Europe, as millions were subjected to occupation, repression, and genocide.

The pact remained in force until June 22, 1941, when Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. The Nazi betrayal marked the beginning of the Eastern Front, one of the most brutal theaters of the war. The Soviet Union, now allied with the Western powers, played a crucial role in the eventual defeat of Nazi Germany.

In the post-war period, the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact became a symbol of Soviet duplicity in the eyes of the West. For decades, the Soviet government denied the existence of the secret protocol, only acknowledging it in 1989 under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev. The legacy of the pact continues to influence relations between Russia and the countries that were affected by the agreement, particularly in Eastern Europe.

The Soviet invasion of Poland, which began on September 17, 1939, was a critical event in the early stages of World War II. This invasion was a direct consequence of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, a non-aggression agreement signed between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union on August 23, 1939. The pact contained a secret protocol that divided Eastern Europe into spheres of influence, with Poland being partitioned between the two totalitarian regimes.

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland from the west, triggering the start of World War II. As Poland struggled to defend itself against the German onslaught, the Soviet Union took advantage of the situation. Claiming to protect the ethnic Ukrainians and Belarusians living in eastern Poland, the Red Army crossed the Polish border on September 17. In reality, the Soviet Union was acting in accordance with its agreement with Nazi Germany, seeking to expand its territory and eliminate Poland as a buffer state.

The Polish military, already weakened by the German invasion, was unable to mount a significant defense against the Soviet advance. With their forces stretched thin and facing overwhelming odds, the Polish government fled to Romania, effectively leaving the country without leadership. Within weeks, Poland was divided along the Curzon Line, with the Soviet Union annexing the eastern part of the country while Germany controlled the west.

The Soviet invasion of Poland had several profound consequences. Firstly, it marked the end of the Polish state, as the country was effectively erased from the map of Europe. The invasion also led to widespread repression in the annexed territories. The Soviet authorities arrested, deported, and executed thousands of Polish military officers, intellectuals, and civilians in a bid to eliminate potential resistance. One of the most notorious acts of this repression was the Katyn Massacre in 1940, where over 20,000 Polish officers were executed by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police.

The invasion also highlighted the brutal realpolitik of the era, as the Soviet Union, despite its claims of being a champion of socialism and anti-fascism, collaborated with Nazi Germany to dismantle a neighboring country. The Soviet actions in Poland had long-term repercussions, contributing to the deep mistrust between Poland and the Soviet Union, a sentiment that persisted throughout the Cold War.

In conclusion, the Soviet invasion of Poland was a key event in the early days of World War II that exemplified the ruthless and opportunistic strategies employed by totalitarian regimes. It not only led to the destruction of the Polish state but also set a precedent for the brutal occupation and repression that would characterize much of Eastern Europe during the war. The invasion remains a dark chapter in the history of Polish-Soviet relations and serves as a reminder of the devastating impact of geopolitical ambitions on smaller nations.

Stalin’s levels of brutality and evilness were equal, if not higher, than that of Hitler; the difference was that Stalin kept his brutal crimes within the USSR. A prime example of that was the Holodomor.

The Holodomor, derived from the Ukrainian words for “hunger” (holod) and “extermination” (moryty), refers to a devastating man-made famine that took place in Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933. It resulted in the deaths of millions of Ukrainians and is widely regarded as one of the most horrific episodes of mass suffering in the 20th century. The Holodomor was not just a natural disaster but a deliberate policy implemented by the Soviet regime under Joseph Stalin, aimed at crushing Ukrainian nationalism and resistance to collectivization.

Background

In the late 1920s, the Soviet Union, under Stalin’s leadership, embarked on a campaign of forced collectivization. This policy sought to consolidate individual landholdings and labor into collective farms. The Ukrainian peasantry, who were primarily small-scale farmers, resisted collectivization, as it meant losing their land, livelihoods, and autonomy. However, for Stalin, the resistance was not just an economic threat. He also feared that Ukrainian nationalism could undermine Soviet control over the republic, highlighting the political motivations behind the forced collectivization.

In response to this resistance, Stalin implemented draconian measures to enforce collectivization, including the seizure of grain and livestock from peasants. The state demanded impossibly high grain quotas, which were rigorously enforced by Soviet officials. Failure to meet these quotas was met with severe punishment, including confiscation of food supplies, livestock, and even seed grain. This left the Ukrainian peasants with nothing to eat.

The Famine

By 1932, the situation in Ukraine had reached catastrophic levels. The Soviet government, however, intensified its policies, sealing off the borders of Ukraine to prevent people from fleeing and blocking the delivery of aid. The requisition of grain continued even as the population starved. Villages that failed to meet grain quotas were blacklisted, meaning they were cut off from all trade and supplies. The result was widespread famine.

The famine peaked in the winter of 1932-1933. People resorted to desperate measures to survive, including eating grass and bark and even resorting to cannibalism. Entire villages were wiped out, and the death toll mounted daily. Estimates of the number of people who perished during the Holodomor vary. Still, most scholars agree that between 3.5 to 7 million people died, with a significant proportion of them being children.

The Role of the Soviet Government

The Soviet government’s role in the Holodomor was not passive; it was an active perpetrator. Stalin and his regime were aware of the famine but continued to deny it publicly. The Soviet Union even exported grain during this period to maintain the illusion of success in its economic policies. The intentional nature of the famine is evidenced by the state’s refusal to allow aid into Ukraine and its measures to prevent starving peasants from leaving the affected areas.

For decades, the Soviet government denied the existence of the Holodomor and suppressed information about it. It was only after Ukraine gained independence in 1991 that the full scope of the tragedy began to be acknowledged and studied.

Legacy and Recognition

The Holodomor remains a deeply painful and contentious issue in Ukraine and among scholars of Soviet history. In Ukraine, the Holodomor is widely recognized as a genocide, an act of deliberate extermination aimed at the Ukrainian people. This view is supported by several countries and scholars, though it is still a matter of debate internationally.

The recognition of the Holodomor as a genocide is based on the argument that Stalin’s policies were intended not just to enforce collectivization but to break the spirit of Ukrainian nationalism and identity. By targeting Ukraine’s grain production and implementing policies that exacerbated the famine, the Soviet regime effectively weaponized hunger against an entire population.

So, I don’t think we should be too appreciative of the Soviets’ role in World War II.

Sources

https://enrs.eu/en/news/882-17-september-1939-the-soviet-invasion-of-poland

https://www.britannica.com/event/German-Soviet-Nonaggression-Pact

https://enrs.eu/news/holodomor-memorial-day

Donation

Your readership is what makes my site a success, and I am truly passionate about providing you with valuable content. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. Your voluntary donation of $2 or more, if you are able, would be a significant contribution to the continuation of my work. However, I fully understand if you’re not in a position to do so. Your support, in any form, is greatly appreciated. Thank you. To donate, click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more than $2, just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Your generosity is greatly appreciated. Many thanks.

$2.00

Leave a comment